Transcription

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/07CHAPTER1:50 PMPage 1235Human Occupation and Mental HealthThroughout the Life SpanMost people live, whether physically, intellectually or morally, in a veryrestricted circle of their potential being. They make use of a very smallportion of their possible consciousness, and of their soul’s resources ingeneral, much like a man who, out of his whole bodily organism, shouldget into a habit of using and moving only his little finger. Great emergencies and crises show us how much greater our vital resources are thanwe had supposed.Wi l l i a m J a m e s ( 1 8 )CHAPTER OBJECTIVESAfter studying this chapter, the reader will be able to:1. Analyze the motivations for performance of occupation.2. Outline changes in performance of occupation from childhood through late life.3. Contrast involvement in work and play occupations at different ages.4. Identify important achievements in occupational development at various life stages.5. Recognize psychiatric disorders that typically appear in childhood, adolescence, adulthood,and later life.6. Describe the effects of mental disorders on performance of occupation at different stagesof life.123

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/071:50 PMPage 124124The desire to act upon the environment andto have an effect is a force that drives andshapes human behavior from birth to death.Occupation, or the expression of this urge throughactivity, is essential for human growth and development. The focus and specifics of occupation changethroughout life as the playing child matures into theworking adult, who later retires and is occupied withnonwork activities. The foundation of occupationrelated habits and skills formed in childhood profoundly influences all later development. Withoutoccupation, growth is frustrated and impaired.This chapter considers how performance ofoccupation develops and changes as the personmatures and ages. We will also look at some of thecommon mental health problems that arise in different life stages, with particular emphasis on theoccupational aspects of these disorders and therole of occupational therapy in evaluation andtreatment. It is important to remember that mental health problems do not always impair the ability to engage in occupation or to use occupation tofurther growth and development.MOTIVATION TOWARD OCCUPATIONTo understand how occupation develops andchanges throughout life, we must first considerwhy humans engage in occupation at all. What arethe reasons? And are the reasons always thesame? Reilly (31) identified a sequence of threelevels of motivation for occupation or action:exploration, competency, and achievement. Exploration motivation is the desire to act, toexplore, for the pure pleasure of it. This is theprimary, or first, motivation for action. Infantsand small children do things because they areexploring what will happen, but adults do thesame thing when they encounter new situations that arouse their interest. Competency motivation is the desire to influence the environment in a specific way and toSection I / History and Theoryget better at it. When motivated by competency, the individual will practice the actionover and over again and seek feedback from theenvironment, including other people, about theeffects of the action. Competency is the secondlevel of motivation; it helps sustain actions thatwere initially motivated only by exploration. Achievement motivation is the desire to attain,compete with, or surpass a standard of excellence. The standard may be an external one ormay be generated by the individual. Achievement is the third and highest level of motivation for occupation. When competent at theaction, the person continues to perform it toachieve success according to a standard.These three levels of motivation—exploration,competency, and achievement—form a continuum that gradually transforms playful explorationinto competent performance and ultimately intoachievement and excellence. The skills that thechild learns through play are later practiced andrefined and finally polished and combined withother skills to enable more sophisticated and complex behavior to emerge.Whenever the individual encounters novelty inthe environment, these three levels of motivationare reexperienced in sequence. New situations andunfamiliar environments bring out the urge toexplore, then to become competent, and then toachieve. This is as true of the working adult andthe retiree as of the preschool child.Kielhofner (21) argues also that different levelsof motivation predominate at different stages inlife. He suggests that the child engages in occupation primarily because of a motive to explore,that the adolescent does so to become competent, and the adult, to achieve. He states thatolder adults are motivated by an urge to explorethe past and their own life’s accomplishments andto explore their present capabilities throughleisure. Let’s now take a closer look at this view ofhow occupation evolves as the individual growsand matures.

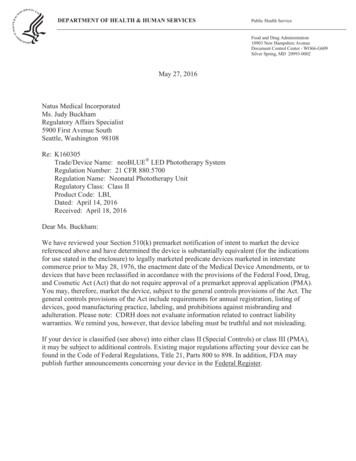

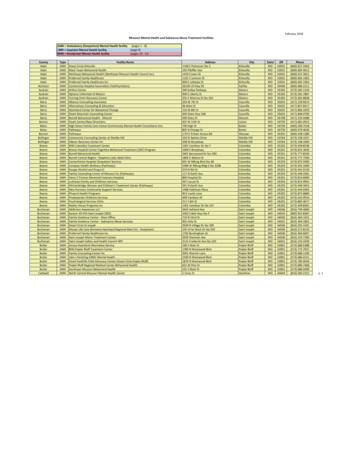

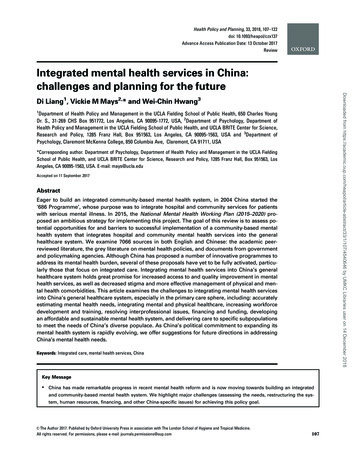

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/071:50 PMPage 125Chapter 5 / Human Occupation and Mental Health Throughout the Life SpanCHANGES IN OCCUPATION OVERTHE LIFE SPANHuman occupation traditionally has been dividedinto two main categories: work and play. Play consists of activities engaged in for pleasure, relaxation, self-exploration, or self-expression. Workincludes all activities through which humans provide for their own welfare and contribute to thewelfare of the social groups to which they belong.For the child, play is the dominant form of occupation; for the adult, work is the dominant form.125The balance and relationship between work andplay change throughout life in certain predictableways (Fig. 5-1).The patterns of work and play illustrated inFigure 5-1 are based on an American notion of normal human life and activity. Although anthropological studies show many similarities in patterns ofwork and play across different cultures, personswho come from other cultural backgrounds mayhave expectations and experiences that differ fromthose illustrated. Keeping this possibility in mind,let us now look at the different life stages.Play yieldsRelationship ofplay and workWork yieldsThe Balance of Work and PlayWaking hours occpiedby work and playLevels of Organization of the Occupaional Behavior CareerCHILDHOODADOLESCENCEADULTHOODOLD AGETime spentin playTime spentin workReality is explored viacuriosity for rule ofcompetent action.Competent behavior islearned and experiencedin games, personalhobbies, and socialevents.Relaxation and recreationsupport the worker role.Exploration of novelsituations allows newroles to be taken on.Play allows the explorationof past achievements andthe unknown future, andmaintenance of competence through leisurepursuit of interest.ExplorationSkills for productivity areacquired and work rolesexplored through imitationand imagination.CompetencyPersonal and interpersonalcompetency are developedin a matrix of cooperation,yielding habits ofsportsmanship andcraftsmanship.AchievementPlay supports the workerroles by providing anarena of retreat andrejuvenation. Explorationin novel situations allowsthe ongoing developmentof new competency forwork.ExplorationRetirement leisure signalsthat the productiveobligation to society hasbeen fulfilled. Past workhas earned for the personthe right to leisure.Leisure replaces work asthe major source of lifesatisfaction.Productive behaviors arepracticed through choresand in school.The work role is practicedand the commitmentprocess of occupationalchoices takes place.There is entry into workerroles with the requirementof establishing andmaintaining a productiveand selfsatisfying career.Retirement brings reducedexpectations forproductivity and personalcapacities for productiveaction are waning.Figure 5-1. The balance and interrelationship of work and play during the life span. (Modified with permissionfrom Kielhofner G. A model of human of occupation: 2. Ontogenesis for the perspective of temporal adaptation.Am J Occup Ther 1980;34:661. Copyright 1980 by the American Occupational Therapy Association, Inc.)

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/071:50 PMPage 126126ChildhoodPlay is the main occupation of the child. Figure 5-1shows that in early childhood the child performsno work at all. Gradually, as children are assignedchores and other responsibilities at home and inschool, they spend some of their time in activitiesthat must be classified as work. The purpose ofplay and work in childhood is distinctive. As children play, they explore their environments, learnabout reality, and develop rules that are used toguide actions. For example, the child learns thatobjects fall to the floor when dropped, that a stoveis sometimes hot, that a favorite uncle will allowthings that Mother will not. These rules aboutmotions, objects, and people (32) are tools thatthe child uses to guide future action and todevelop skills. This childhood learning about howthe world works is a foundation upon which lateraccomplishments are built. Thus the playing childacquires knowledge and develops rules and skillsthat underlie and support the work of the studentand the adult worker.Research confirms that play is essential forlater development (1). Studies of many speciesshow that important neurological connections,such as cerebellar synapses and long fiber tracts,are formed in their greatest numbers during theperiod when play is most vigorous in the younganimal. These connections establish a foundationfor skillful, responsive motor actions. Anotherimportant function of play for young animals is topractice and rehearse the subtle social behaviorsthey will need as adults (1). Thus imitation andexploration of future occupational roles areenacted in play. Through fantasy and imitation,the child investigates and experiences variousadult roles (mommy, doctor, teacher, and so on).This experience, known as the fantasy periodof occupational choice, is the first step in thethree-stage process of choosing a career or adultoccupation (12).During play, the child also learns the joy of having an effect on the world and on other people.Section I / History and TheoryThis helps form an image of the self as personallyeffective and powerful, thus developing andenhancing a sense of personal causation. Thepleasure that the child takes in one activity overanother helps form interests that will motivate lifechoices.Although the child is not expected to domuch work, the productive activities of thechild are very important for later development.Studies have shown that industriousness in childhood is associated with job success and personaladjustment in adult life (38). Chores and schoolwork are the major productive activities of childhood. By engaging in these tasks over time, thechild acquires habits of industry and responsibilityand learns to schedule activities so that time alsoremains for play. Some tasks, such as handwriting,have clear associations with work. Even very youngchildren can describe the difference between workand play and may describe their time in school as“work” (23). Although play remains the majoroccupation throughout childhood, the maturingchild spends increasing amounts of time in activities that lay a foundation for the future role ofadult worker. Habits and routines are developedand established.AdolescenceAdolescents, like children, continue to spendmore time in play than in work. However, nowmotivated more by the desire to become competent than by the urge to explore, they chooseactivities in which practice and the habits ofsportsmanship and craftsmanship make the difference between success and failure. Whetherthe activity is the track team, the chess club, orvideo games, the adolescent approaches it withdetermination to master and succeed. The biological changes of puberty interact with the adolescent’s use of occupation to motivate a growinginterest in social activities that provide opportunities to explore and practice social and sexualbehaviors.

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/071:50 PMPage 127Chapter 5 / Human Occupation and Mental Health Throughout the Life SpanThe work of the adolescent, like the work ofthe child, consists of school and chores. Schoolwork becomes more rigorous and more time consuming, in keeping with the adolescent’s growingcognitive capacity and discipline. Depending onthe parents and the family situation, the choresmay also be increasingly challenging. Many adolescents take on part-time jobs, which provideimportant experiences of what life is like in theadult working world and give feedback about theadolescent’s readiness for work.Adolescents are concerned about what theywill do with their lives as adults, and occupationalchoice is generally viewed as one of the mostimportant developmental tasks of adolescence.The process that began in the fantasy period ofchildhood enters a new stage, known as the tentative period. During this time, the adolescent considers possible adult occupations; this evaluationconsiders interests and likelihood of success.Finally, the adolescent weighs any choice in termsof personal values and achieved or expected placein the social system. From this overwhelmingmass of factors, the adolescent must finally choosea career but may remake this decision severaltimes throughout life.Once the decision is made, the adolescent beginsto work toward it, for example by enrolling in atraining program or looking for a job. This beginsthe realistic period, in which the choice of career isexamined in light of personal needs for achievement, satisfaction, status, and economic security.For example, if the chosen career is one in whichjobs are scarce (e.g., acting) or the pay is low, theperson may reconsider this decision and then mustcome up with alternatives and choose among them.Thus occupational choice is crystallized andacted upon during adolescence, although for adolescent children of affluent parents the choicemay be delayed into early adulthood. By contrast,adolescents from disadvantaged backgrounds mayencounter overwhelming obstacles to realizingtheir occupational choice. In times of high127unemployment, the adolescent with few skills maybe denied employment or forced into a job thatfeels demeaning and unsatisfying. Ultimately, theprocess of occupational choice may be repeatedby the adult who decides or is forced to changecareers later in life.AdulthoodThe adult spends many hours in work, leaving little time for play. The work of the adult centers onthe occupational role selected through the processof occupational choice. This work, which is notnecessarily salaried (consider the homemaker),consumes much time and energy and allows forexpression and gratification of the urge to achieve.For many adults, there is the additional work ofparenthood.Adults work to provide for their own needs andthose of their families. Beyond this, they work toproduce something of value to the rest of society.Having a productive work role is important for theself-esteem of the adult; it bestows a sense ofidentity, a place in the social hierarchy, and a reason for being. Adults who are unemployed orunderemployed (working at jobs that are beneaththeir capacities) often have negative views of theirown abilities and worth. They may see themselvesas incompetent and helpless rather than as competent and achieving members of society.Despite the fact that working adults have littletime for play, the time they spend in leisure andrecreation serves an important function: It restoresand refreshes their energies to work again. Theword recreation actually means “the creation(again) of the laboring capacity.” Different peoplefeel different degrees of need for recreation; somepeople spend almost all of their time working,leaving only negligible amounts for play, andappear to be quite satisfied and happy. Otherslimit their work to a specific number of hoursprecisely because they want to make time forleisure pursuits.

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/071:50 PMPage 128128In middle and later adulthood the individuallooks toward the future and retirement and beginsto explore and plan for this next stage. The majorissue is the replacement of work with some otheractivity that will fill the hours, that will compensate for the loss of the worker role and of thesocial relationships with co-workers. Jonsson andcolleagues (19) analyzed statements of peopleanticipating retirement and classified them asbelonging to three types: Regressive (anxious and uncertain, dreadingthe future) Stable (expecting little change—may be eitherpositive or negative) Progressive (may be either positive, focusingon new activities, or negative, focusing on getting rid of unpleasant work situation)Examples of statements reflecting these threestyles of response to retirement are shown inBox 5-1. Successful adjustment to retirement mayrequire a reassessment of interests and the development of new hobbies and goals. Without thisSection I / History and Theorypreparation, the transition from full-time work toretirement can be stressful, even devastating.Later AdulthoodDuring the latter part of life and certainly afterretirement, the number of hours spent in workdramatically decreases. Thus vast quantities oftime suddenly become available, and decisionsmust be made about how to fill the hours. Leisurereplaces work as the primary occupation, althoughmany retirees continue to serve productive socialroles (e.g., as volunteers) that can only be classified as work.The loss of a work role or of the role of parentand homemaker represents not just the loss ofactivities that once filled one’s day but also of status and social identity. To adjust, the older adultneeds goals and occupations that provide satisfaction and opportunities for success and that supporta sense of self-worth. Older adults find particularmeaning in maintaining leisure activities that havebeen lifelong interests (17). Each older personBOX 5-1SAMPLE STATEMENTS OF PERSONS ANTICIPATING RETIREMENTRegressive: “I can’t imagine not going to work. I don’t have a plan for how to spend the time.”Stable (positive): “I do so many things now that I will be continuing [golf, volunteer at church], that I thinkvery little will change except maybe I’ll have more time.”Stable (negative): “Well, you know, I can’t say that life will be different. Just more of the same. The sameold, dreary routine.”Progressive (positive): “I have just been waiting so long for this. I’ll have more time for the botanicalgarden and the arthritis group and travel and just everything that I want to do more of.”Progressive (negative): “Definitely retirement will be an improvement for me. My whole body aches aftera long day at work, and frankly, I’m a little tired of the whole situation. It will be a relief.”Fictional composites, with acknowledgment to Jonsson H, Kielhofner G, Borell L. Anticipating retirement: The formation of narrativesconcerning an occupational transition. Am J Occup Ther 1997;51:49–56.

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/071:50 PMPage 129Chapter 5 / Human Occupation and Mental Health Throughout the Life Spanlives in a particular environment, has a particularoccupational history, and has specific interests.The ability to continue living with maximum independence in the community is highly individualand requires client-centered support (16).In the words of the 18th-century poet WilliamCowper, “Absence of occupation is not rest,/Amind quite vacant is a mind distressed.” Thus oneof the important tasks of this stage of adult life isto identify and develop interests and challengesthat will sustain one’s sense of independence andself-worth.Occupational DevelopmentBecause occupational therapy practitioners areconcerned primarily with a person’s ability todevelop and maintain satisfying occupational patterns, it is helpful to understand the functions, typical patterns, and development of occupationduring the major life stages. The child samples andlearns about the world through playful exploration,laying a foundation of motor and social skills. Theadolescent, acting on the drive to become competent, practices and refines these skills and consolidates them into habits and roles. The adult,wishing to achieve and contribute, makes choicesabout career and life goals and selectively continues to develop and elaborate the skills and habitscultivated earlier in life. In later life, once careerpatterns are established and especially after retirement, the older adult may wish to integrate thelong-abandoned interests of a younger self. Thusfavored activities may be rediscovered and pursued again in later life. New occupations can bediscovered and old interests reexplored.We have said that the ability to engage in occupation is one of the signs of mental health andthat mental illness can interfere with a person’sability to carry out daily life activities and to fulfilloccupational roles. Let’s look now at other significant factors in mental health at various ages andthe kinds of mental health disorders that tend tooccur at different stages of life.129MENTAL HEALTH FACTORS THROUGHOUTTHE LIFE SPANThis section is an overview of the mental healthneeds of clients of various ages and the ways inwhich occupational therapy intervenes to helpthem. The section is divided according to six majorlife stages: infancy and early childhood, middlechildhood, adolescence, early adulthood, midlife,and late adulthood and aging. For each stage, normal development and the kinds of mental healthproblems that sometimes arise are brieflydescribed. The general goals and methods of occupational therapy are identified; and, where relevant, special intervention settings and evaluationand treatment methods are discussed. More detailon specific diagnoses and settings can be found inChapters 6, 7, and 9.While reading this section and after finishingthe chapter, the reader should examine Table 5-1,which summarizes aspects of human occupationfor each age group and lists major mental disorders that typically occur in the respective agegroups. A case example later in the chapter illustrates the interactions among developmental tasks(10), the development of human occupation, environmental risk factors, and age-specific vulnerabilities to mental illness.Infancy and Early ChildhoodBabies start life with enormous needs and wantsand absolutely no ability to satisfy them on theirown. Parents have to be able to figure out whatbabies want—whether the infant is hungry orthirsty or needs to be burped or cuddled orchanged—and then provide it. To be able to relateto other people later on and to engage in activitiesthat involve others, infants and small children needto learn to trust their parents and then people ingeneral. In addition, they need to learn to communicate their needs and feelings and to control theirimpulses. Thoughtful interaction and consistent

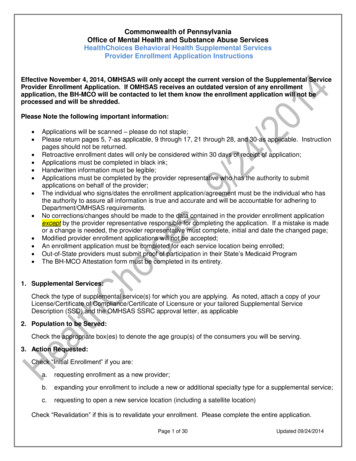

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/071:50 PMPage 130TABLE 5-1 SOME ASPECTS OF DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN OCCUPATION SUBSYSTEMSAND RISKS OF MENTAL DISORDERS BY AGE GROUPMIND–BRAIN–BODYMAJOR MENTAL DISORDERSAGE GROUPVOLITION SUBSYSTEMHABITUATION SUBSYSTEMPERFORMANCE SUBSYSTEMBY TYPICAL AGE OF ONSETChildhoodPersonal causationdeveloping throughsocial interactionsand play; values ofculture taught;interests enactedthrough choice ofactivitySelf-maintenancehabits; routinesestablished byparental scheduling;gradual shift tomore control bychild; student, friendroles learnedTremendous developADHD, PDD, autism,ment of skills transAsperger's syndrome,forming from helpOCD, ODDless infant to activeagent in worlds offamily, play, school; ageof exploration and increasing competenceAdolescenceIncreasing drive forExploration of roles; role Continued development Schizophrenia, subautonomy; considerexperimentation;of skills in motor,stance-related disoring choice of occuexpanded; more indepprocess, communicaders, mood disorderspation; weighing parendent student role;tion, interaction; socialental vs. peer values;first enactment ofrelations with peersshifting interests affecworker role; increafostering expandedted by peer or environsing self-regulation;communication andmental pressureacquisition of habitsinteraction skillsof time managementAdulthoodMaturation of personal Multiple roles (spouse,Peak abilities; mastery of Schizophrenia, moodcausation, interests,parent, worker,many work-relateddisorders, substancevalues culminating infriend, volunteer,skills; declining capacabusechoice of occupation;church member);ity may come fromvalues increasinglydespite role conflict,physical changes leadimportant in motivatmultiple role involveing to reduced energy,ing behavior;ment satisfying;need for eyeglasses,interests possibly nothabits and routineshearing aids; continuedaddressed by work;influenced by need tohigh level of involveavocational activitiesmanage time forment helping sustainpossibly especiallymultiple involvementsgreatest capacity andfulfillingskill levelLater adulthoodSense of efficacyPotential loss of majorAge-related changes inAlzheimer's, vascular,possibly challengedroles and rolemusculoskeletal, neuroand other dementias;by diminished physicompanions throughlogical, cardiopulmonarydepression; polysubcal capacity;retirement, physicalsystems varying instance abuse (prescripimportance (value) ofdisease, death (workintensity; adjustments,tion medications,work possibly declinrole, spouse role, friendadaptations to continuealcohol)ing as family androle); family roles andusing skills (e.g., energysocial values increase;social roles increaseconservation, pacing,opportunity inin importance; habitsrest periods); adaptiveretirement to pursueof a lifetime wellequipment, environinterests moreestablished; new habits mental aids helpingrigorouslyhard to acquiresustain skillsADHD, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder; PDD, pervasive developmental disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder.Data from Kielhofner G. A Model of Human Occupation: Theory and Application. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.130

Early CH05 123-144.qxd11/28/071:50 PMPage 131Chapter 5 / Human Occupation and Mental Health Throughout the Life Spandiscipline by the parents help the child acquirethese skills. A stable, secure, and predictable environment is one of the most important factors inhelping the child at any age to develop trust in self,other people, and the world in general.While all of this psychosocial development isgoing on, the child is developing in other ways too.Sensory abilities are becoming more refined, motorskills better coordinated, and perceptual and cognitive abilities more complex. The child constantlyuses and refines developing abilities to learn moreabout the world and how to interact with it.It is unusual for mental health problems to bediagnosed in infancy and the preschool years.Often problems that are brought to the attentionof psychiatric professionals are quite severe. Someof these problems are believed to have biologicalcauses, meaning that the behavioral or emotionaldisorder is caused at least in part by somethingphysical within the body or the brain.Attention deficit disorder (ADD), attentiondeficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) are in thiscategory. The child with ADD or ADHD has ashorter attention span than is normal for a child ofsimilar age. Jumping from activity to activity, oftenwith a high level of energy (hyperactivity) but withan apparent inability to concentrate long enoughto finish many of the tasks attempted, the childleaves a trail of chaos and confusion. It is not hardto imagine how this can interfere with learning.PDD is a cluster of disorders occurring in veryearly childhood and impairing the ability todevelop in many areas. Infantile autism is oneexample. This is a disorder in which the veryyoung child fails to respond to other people, oftenignoring them completely. Autism is believed tohave an underlying biological component, andresearch supports this view (30). Children withautism differ from other children in the way theyprocess and understand sensation (39). The childis usually slow to develop language skills, thelearning of which seems to rely upon interactionswith others. In addition, children with autism may131exhibit strange mannerisms, such as wiggling theirfingers in front of their eyes, and bizarre interests,for example in bright lights or spinning objects.Occupational therapy for children with thesedisorders often focuses on sensorimotor or sensory integrative treatment approaches, which arebelieved to affect the underlying biological problem. Occupational therapy assistants (OTAs) maycarry out such treatment only under the directsupervision of occupational therapists (OTs) whohave special training in these approaches.Psychoanalytic (object relations) methods aresometimes used instead, but these also requiredirect supervision and special training. A morebehaviorally oriented treatment approachfocuses on the development of self-care skills(e.g., shoe tying) through direct instruction andreinforcement.Building a trusting relationship and modifyingthe environment to enable success are often thetwin foundations of intervention with children.Baron (3) presented a case study of a 4-year-oldboy who had oppositional defiant disorder (ODD).A structured play experience with the occupationaltherapist over many weeks helped this child giveup his resentful and argumentative behavior anddevelop a more spontaneous and genuineapproach to play. Key elements of this treatmentincluded a slow and careful building of trustthrough brief, frequent, one-on-one play withactivities selected by the child from a limitedchoice given by the therapist; modification of thesocial play environment so that competition wasreduced; and teaching and reinforcement of socialskills such as taking turns.Another serious mental health problem ofearly childhood is reactive attachment disorder, inwhich the child stops responding to other peoplebecause he or she has be

Chapter 5 / Human Occupation and Mental Health Throughout the Life Span 125 CHANGES IN OCCUPATION OVER THE LIFE SPAN Human occupation traditionally has been divided into two main categories: work and play. Play con-sists of activities engaged in for pleasure