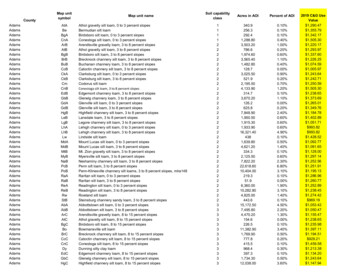

Transcription

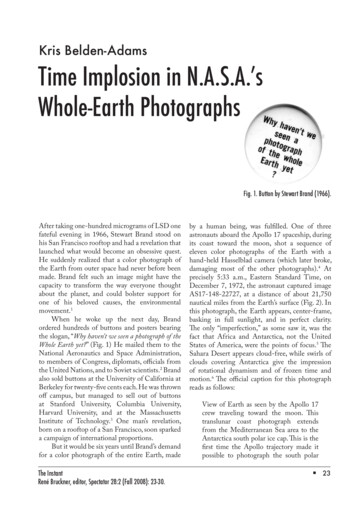

Kris Belden-AdamsTime Implosion in N.A.S.A.’sWhole-Earth PhotographsFig. 1. Button by Stewart Brand (1966).After taking one-hundred micrograms of LSD onefateful evening in 1966, Stewart Brand stood onhis San Francisco rooftop and had a revelation thatlaunched what would become an obsessive quest.He suddenly realized that a color photograph ofthe Earth from outer space had never before beenmade. Brand felt such an image might have thecapacity to transform the way everyone thoughtabout the planet, and could bolster support forone of his beloved causes, the environmentalmovement.1When he woke up the next day, Brandordered hundreds of buttons and posters bearingthe slogan, “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of theWhole Earth yet?” (Fig. 1) He mailed them to theNational Aeronautics and Space Administration,to members of Congress, diplomats, officials fromthe United Nations, and to Soviet scientists.2 Brandalso sold buttons at the University of California atBerkeley for twenty-five cents each. He was thrownoff campus, but managed to sell out of buttonsat Stanford University, Columbia University,Harvard University, and at the MassachusettsInstitute of Technology.3 One man’s revelation,born on a rooftop of a San Francisco, soon sparkeda campaign of international proportions.But it would be six years until Brand’s demandfor a color photograph of the entire Earth, madeThe InstantRené Bruckner, editor, Spectator 28:2 (Fall 2008): 23-30.by a human being, was fulfilled. One of threeastronauts aboard the Apollo 17 spaceship, duringits coast toward the moon, shot a sequence ofeleven color photographs of the Earth with ahand-held Hasselblad camera (which later broke,damaging most of the other photographs).4 Atprecisely 5:33 a.m., Eastern Standard Time, onDecember 7, 1972, the astronaut captured imageAS17-148-22727, at a distance of about 21,750nautical miles from the Earth’s surface (Fig. 2). Inthis photograph, the Earth appears, center-frame,basking in full sunlight, and in perfect clarity.The only “imperfection,” as some saw it, was thefact that Africa and Antarctica, not the UnitedStates of America, were the points of focus.5 TheSahara Desert appears cloud-free, while swirls ofclouds covering Antarctica give the impressionof rotational dynamism and of frozen time andmotion.6 The official caption for this photographreads as follows:View of Earth as seen by the Apollo 17crew traveling toward the moon. Thistranslunar coast photograph extendsfrom the Mediterranean Sea area to theAntarctica south polar ice cap. This is thefirst time the Apollo trajectory made itpossible to photograph the south polar23

time implosionice cap. Note the heavy cloud cover inthe Southern Hemisphere. Almost theentire coastline of Africa is clearly visible.The Arabian Peninsula can be seen atthe northeastern edge of Africa. Thelarge island off the east coast of Africa isthe Republic of Madagascar. The Asianmainland is on the horizon.7According to N.A.S.A., the image was takenat precisely five hours and six minutes after launch,and about one hour and forty-eight minutes afterthe spacecraft left its parking orbit around theEarth to begin its trajectory to the moon.8 Thisimage, assumed to be a snapshot of a fraction oftime, is labeled with temporal precision—but nottoo much precision. It was taken sometime withinthe thirty-third minute after five o’clock in themorning, Eastern Standard Time. However,light, as we see it in the photograph, accumulatedon light-sensitive film over just a fraction of asecond, not a full minute. Big Blue Marble, as thepicture would come to be titled, exemplifies anenduring normative perception that photography’srelationship to time is that of instantaneity.Arguments that the photographic medium hasa finite, instantaneous relationship to time havebeen the mainstay in photo-history discourse untilthe 1990s. The early motion studies of EadweardMuybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey, the snapshotsof Jacques-Henri Lartigue, the “decisive moments”of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the stroboscopic imagesof Dr. Harold Edgerton, and the 1960s snapshotaesthetic reflect and maintain this perception thatthe photograph captures the appearance of itssubject in the fraction of a moment.But instantaneous-time photographs suchas Big Blue Marble also have a complicated,sometimes convoluted, relationship to time. InCamera Lucida, Roland Barthes maintains that thephotograph has a peculiar capacity to represent thepast in the present, and thus to imply the passingof time in general.9 As a consequence, Barthesargues, all photographs speak of the inevitability ofour own death in the future. Moreover, he suggeststhat photography’s most important attribute is itsability to fracture the linearity of “lived time,” orthe “logico-temporal order,” to cause a collision ofpast, present and future in the viewer.1024FALL 2008Big Blue Marble is an example of just such aconvolution of time in instantaneous photographs.The image depicts a planet very much in the throesof motion, as Marta Braun suggests: whereas the other photographs depictmovements that occur in instants oftime too fast to ever be seen by thenaked eye, this photograph is a picture ofmovements—the diurnal rotation of theearth and the much longer rotation of themoon—that are too slow. The invisibilityof the earth’s motion is echoed by theinvisibility of all human presence.11Thus, in this photograph, time is extended.What we see is a duration of time. Yet the imagewas snapped in an instantaneous fraction of asecond. These apparently conflicting attributes oftime—that is, time as it appears in instantaneousphotography—were explained by Charles SandersPeirce: “Even what is called an ‘instantaneousphotograph,’ taken with a camera, is a composite ofthe effects of intervals of exposure more numerousby far than the sands of the sea.”12But the temporal attributes of Big Blue Marbleare yet more complicated. Light collected on filmwas actually reflected from the Earth’s surface ina split second in the past that took time to travelthrough space and collect on film.13 Not only doesthe image reveal the conventional appearance ofthings in the past—as is conventionally assumedof instantaneous photographs—it also presentsthe appearance of the Earth in a time previous tothe past-time assumed by the viewer. N.A.S.A.’sBig Blue Marble then represents an image withan instantaneous relationship to time (thanks tothe camera’s quick shutter operations), but whichactually depicts a duration of time and movementthat transpired in the past. The photographexemplifies Geoffrey Batchen’s suggestion thatphotography is “in time but not of time.”14Big Blue Marble’s Re-GenerationApollo 17, the spacecraft from which Big BlueMarble was photographed in 1972, was the onlymanned spacecraft ever to orbit far enough awayfrom the Earth that it could view the entire planet

Belden-Adamsin full sunlight. Later missions have flown too of cloud positioning, based on the informationclose to the Earth to observe the entire globe.15 about cloud location collected from satellitesFor this reason, according to William Stefanov of over a span of time. The duration of time requiredN.A.S.A.’s Image Science and Analysis Laboratory, to collect data is variable and subjective, and isany image showing the surface of the entire Earth determined by the time it takes for every squarewhich was made after 1972 is a composite digital mile of the Earth to have its image captured by thephotograph. These images are made with the aid satellites. The image from 1996 (Fig. 3) was madeof computer software, which blends photographs from four months of data. The image from the yearfrom dozens of satellite images to produce an 2000 (Fig. 4), in comparison, was made from oneimage of what the Earth might look like if the week of data in late March. If clouds covered mostplanet were cloud-free or, as in one example I will of America during the period of data collection,analyze, illuminated all at once.16the country likely will be obscured by clouds in theAlthough digital whole-Earth montages resulting image. Operators, however, can choose toare difficult to disoverride the computertinguish from singlegenerated “averageexposure photographsappearance” cloud coverfrom space, the comproduced by the dataposite images are theset and mathematicalresult of the seamlessfigures (also called thedigital combination ofcomputer’s “decisionseparate photographs,trees”). They can opteach of which relate toinstead to make a thinlya different moment inclouded, or even cloudtime, into a compositefree, picture of thepicture presenting whatEarth.19appears to be a single,The digital wholeinstantaneous momentEarth photographin time.titled The New World:Whole-EarthGOES (Geostationarydigital images areOrbiting Environmentalmade by a computerSatellite) Clouds Overprogram that collects Fig. 2. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Big Blue the Face of the Earth,satellite data about Marble #22727, Taken from aboard Apollo 17, Dec. 7, 1972, atAug. 2, 1996 (Fig. 3)the appearance of the 05:33 Eastern Standard Time.is a composite imagesurface of the Earth andthat is very similar incombines that information to make a composite coloration, cloud covering and in the degreeimage. ARC Science Simulations, whose clients of surface detail to the original 1972 Big Blueinclude N.A.S.A., is among the companies that Marble single-exposure photograph.20 However,make this software.17 According to ARC’s web although the digital image could be mistakensite, the goal of their programs is, admittedly, to as a single-exposure image, the 1996 compositeproduce “photo-realistic,” “accurate, high quality photograph has a different relationship to time.earth imagery [that] can compare remarkably It was made from four months of cumulativewell to photographs from space.”18data, in order to assure that every part of theW h o l e - E a r t h - c o m p o s i t e - g e n e r a t i n g Earth’s surface was eventually visible belowcomputer programs produce images based on the cloud cover. In this photograph, Norththe mathematical “probability of appearance” of and South America, not Africa, are the centralthe subject. Clouds, for instance, do not appear focus. Swirls of dynamic clouds avoid obscuringhaphazardly. Mathematical calculations performed the western half of the United States, but areby the computer program determine the likelihood not omitted altogether—presumably because aTHE INSTANT25

time implosionFig. 3. (above) National Aeronautics and Space Administration,The New World: GOES (Geostationary-Orbiting EnvironmentalSatellite) Clouds over the Face of the Earth, Aug. 2, 1996. (Digitalcomposite image.)cloudless country might not be believable.The New World is a photograph of theAmericas, as they would have appeared in “average”appearance, over four months (with some possibleaesthetic modifications of this data). The planetEarth that appears in this photograph never existedexactly as we see it. The New World, like all digitalcomposite whole-Earth images, is an abstraction.Stephen Talbott suggests that this phenomenonis the result of the way that computer technologyprocesses data: “What can be mapped from thehuman being to a machine is always and onlyan abstraction.”21 In The New World, abstractionoccurs at several levels of the production process.First, reflected light that left the Earth’s surfaceseveral split-seconds in the past is collected as aninstantaneous photograph—which has an innateassumed relationship to the past. Althoughphotographs have a unique capacity to represent thepast in the present, as Barthes notes, photographicrepresentations of time are always much morecomplicated than that.22 Because a photographpresents an image of the past which is beheld inthe present, every photograph implies the passingof time in general—and by extension, it remindsus of the inevitability of our own deaths.23 WholeEarth photographs take this convolution of tensesone step further. All of the Earth’s motions andsurface activities, which are so slight that theycannot be detected by the human eye or camera—are nevertheless present in the image. Thus, these26FALL 2008Fig. 4. (above) National Aeronautics and Space Administration, BigBlue Marble: Next Generation, made with MODIS data, File Name:terra globe0047, 2000. (Digital composite image.)instantaneous-time images of imprinted light fromthe past also embody duration.The piecing-together of a tapestry of satellitedata from different times and locations, and theconversion of this data into mathematical figuresfor the purpose of producing a product basedon an average appearance, is all a function ofproducing an image of an hypothetical, abstractEarth. Thus, the temporality depicted in a digitalcomposite N.A.S.A. whole-Earth photograph is asimulated time. The New World and other wholeEarth composites represent a complex synthesisof time, enabled by technological advance. Thesetime abstractions can be seen as the products of aculture of “informediation” and “simulation” whichare enabled by computer technology—the verytool used to compose these images.Electronic media critic and theorist KimonValaskakis argues that the digital age has enabledus to enter a state of “informediation,” in whichan amazingly realistic simulation and synthesisof events and things is possible.24 Valaskakis alsowarns that this phenomenon, when not clearlypresented as educational, abstract, and hypothetical,has consequences, including “the increasedprobability of Reality Blur, which may be definedas a progressive blurring of the distinction between

Belden-Adamstruth and fiction, reality and fantasy, actuality andpotentiality.”25Whole-Earth photography clearly exemplifiesValaskakis’ characterization of informediation andits effects. When The New World and Big BlueMarble: Next Generation composite photographsappear without explicit captions to explain theirbasis in abstraction, these images conflate fact andfiction. ARC Science Simulations, as mentionedearlier, claims that producing “photo-realism,” orblurring the line between fact and fiction, is actuallythe desired goal of whole-Earth photographs.What we see in The New World, a partial productof ARC software and data, is a convincingly realabstraction which carries with it an air of scientifictruthfulness because it is based on mathematicalscience—a trustworthy product of positivisttechnological advance.By presenting the averaged, hypotheticalappearance of the Earth over time, what we seein a whole-Earth photograph is an image of thegeneral, the schematic, and the ideal. The logic of awhole-Earth photograph is at odds with what PeterGalassi has argued is photography’s unique ability torepresent specificity, or “thisness”—following fromthe logic that photography is the heir to the “spiritof realism” inherent in art since the Renaissance.26Other art historians, such as Jonathan Crary, haveargued otherwise. Crary suggests that modern artwas marked by a departure from a sense of the realand the indexical: “From the mid century on, anextensive amount of work in science, philosophy,psychology, and art was coming to terms in variousways with the understanding that vision, or anyof the senses, could no longer claim an essentialobjectivity or detachment from certainty, specificity andobjectivity, its affinity for the general andthe subjective, and its nature (as a product ofmathematical and computer science) makes it anexample of what Crary argues has fundamentallybeen at stake in modern vision starting in thenineteenth century. But digital composite wholeEarth photographs also exemplify a phenomenonJeffrey Sconce describes as a crisis of “simulation,”in which signifiers cease corresponding to objects:Where there was once the “real,” thereis now only the electronic generationand circulation of almost supernaturalsimulations. Where there was once stablehuman consciousness, there are now onlyghosts of fragmented, decentered, andincreasingly schizophrenic subjectivities.Where there was once “depth” and “affect,”there is now only “surface.” Where therewas once “meaning,” “history,” and a solidrealm of “signifieds,” there is now only ahaunted landscape of vacant and shiftingsignifiers.28Frederic Jameson similarly notes whathe sees as a postmodern play of surface andsimulation. He argues that four binaries have beencollapsed in postmodern culture: “essence andappearance,” “latent and manifest,” “authenticityand inauthenticity,” and “signifier and signified.”Jameson contends that the dissolution of thesebinaries has created a new cultural environmentof “depthlessness.”29 Digital whole-Earthcomposites antagonize Jameson’s binary of“authenticity and inauthenticity” (by givingconvincingly “photo-realistic,” and therefore“authentificated” form to the imaginary andabstract, “unauthentic” Earth). However, theactual Earth (“the signified”) is not, however,synonymous with its binary opposite, the digitalcomposite image (“the signifier”). This binaryis preserved by whole-Earth images. WholeEarth composite photographs are icons of theplanet Earth, made by abstractions of reflected,“indexical,” light. This light is synthesizedmathematically to produce an “averaged” and“simulated”—but not actual, or faithfullyindexical – appearance of the planet.However, tempting as it might be to castwhole-Earth digital composite photography as amanifestation of Jameson’s loss of “authenticity”and a sign of “depthlessness” in the electronic age,or to condemn whole-Earth digital compositesfor prompting a loss of photography’s assumedrelationship to reality because they implode time,these images are part of a lineage of compositepractice that began questioning photographicindexicality from the time of the medium’sinvention.30 Composite photographs are—andalways have been—abstractions. To Jameson, theTHE INSTANT27

time implosionimmediacy of the electronic age has produced“depthlessness.” Stephen Talbott similarlyarticulates that modern life “leaves no room to digestthings,” producing reaction rather than synthesis.31Yet whole-Earth digital composite photographsproducts of a complicated technical synthesis.They are an expression of an age in which timehas been compressed, sped up, made simultaneous,measured and defined in ever-more infinitesimalincrements. If time has become elastic in an age ofinstantaneous communication and rapid travel, sohave representations of it. Photography’s peculiarlink to temporality lends it a kind of realism tothe experience of time that Barthes described as“false on the level of perception, true on the levelof time.”32A more recent whole-Earth photograph, suchas Big Blue Marble: Next Generation (Fig. 4), raiseseven more questions about time. It was the resultof one week of data in March of 2000, collectedby MODIS sensors aboard the Terra and Aquasatellites. Giving central focus to North America,this image shows a greater degree of surface detailthan evident in The New World. The Earth’s terrainvaries from green to brown. Swirls of cloudscongregate over Canada, the North Pole, and overthe western coast of South America. The rest ofthe globe is relatively free from obstructive cloudcover.Big Blue Marble: Next Generation representssignificant technological improvements over TheNew World:Coupled with improved geolocation data,computer hardware, server connectivity,and image processing made it becomepossible to produce and serve frequentlyupdated, global mosaics at approximatelyone kilometer per pixel or five kilometersper pixel resolution.33In Big Blue Marble: Next Generation, improvementsin computer systems also reduced data-collectingtime to one week (a significant decrease from thefour months of data-collecting needed to makeThe New World in 1996). Advances in computertechnology rendered the imprint of additionaltime unnecessary, and enables the production ofan image as quickly as possible. Timothy Druckrey28FALL 2008argues that the computer, a unique inventionwhich sprang forth from the habits and prioritiesof modernity and postmodernity, enables the desireto be fast-acting and efficient—desires he suggestsdefine our time.34 In the book Liquid Modernity,sociologist Zygmunt Bauman also redefines theage of modernity and technological advance asa temporal obsession with “acceleration and theresulting ability to manipulate time.”35Time in a digital composite image likeBig Blue Marble: Next Generation exemplifiesan obsession with time’s relentless passage andfluid nature. In them, time is compressed into animaginary representation of instantaneous time,despite the fact that it is actually the product ofa one-week duration, viewed from the variouspoints of view of dozens of satellites. As time isdistended, montaged-together, compressed andrepackaged to form a new idealized, instantaneousversion of time, time’s very laws, contradictionsand operations are subject to interrogation.Dorthe Gert Simonsen argues that relentlesstechnological advance, and an increasing valuationof speed, inevitably led to an implosion of ourunderstanding of time: accelerationhascontinuouslycompressed time and space throughoutmodernity, reaching a final annihilationof temporal and spatial co-ordinatesin the present society of instantaneouselectronic communications Ratherthan continuously compressing andfinally annihilating time and space, speedhas produced diverse and interacting,occasionally conflicting, times andspaces.36Composite whole-Earth photographs are anexample of experimentation with the conflictingproperties of time. In them, a duration of lightcollected from the past appears as instantaneoustime. N.A.S.A.’s whole-Earth photographs alsoare the result of the seamless digital merging oftens of thousands of separate satellite photographs,each of which is an imprint of a different momentin the past, into a composite picture presentingwhat appears to be a single instant. What we seein digital composite images is a complex synthesis

Belden-Adamsof snapshots taken from various viewpoints inspace, stitched together to appear unified. Space iscollapsed in whole-Earth photographs, and moreprofoundly, time is fractured and recomposed.These time abstractions express the anxieties ofa culture coming to grips with the ubiquity ofaccelerating speeds and collapsed time, whichwas itself partly enabled by the technology usedto make these composite photographs. WholeEarth photographs, therefore, provide a uniquecommentary upon the tools, as well as the time,which produced them.Kris Belden-Adams is a doctoral candidate in Art History at the City University of New York’sGraduate Center in New York, N.Y., and also teaches Art History at the Kansas City Art Institute.She is writing a doctoral dissertation on various twentieth-century vernacular photographic practices’complicated relationship to time; this essay is a condensed version of one of its chapters.Notes1 Vicki Goldberg, The Power of Photography: How Photography Changed Our Lives (New York: Abbeville Publishing Group, 1991),53. In fact, as former Vice President and Nobel Peace Prize winner Al Gore attests, this has been the case. Big Blue Marble (Fig.1) appears at the start of Gore’s Academy-Award-winning documentary on global warming, An Inconvenient Truth (dir. DavisGuggenheim, Lawrence Bender Productions, 2006).2 Goldberg.3 Ibid. 54.4 Denis Cosgrove, “Contested Global Visions: One-World, Whole-Earth, and the Apollo Space Photographs,” Annals of theAssociation of American Geographers 84, no. 2 (1994). 270.5 Ibid. 278. Denis Cosgrove also argues suggestively that: “ representations of the globe and the whole Earth in the twentiethcentury have drawn upon and constituted a repertoire of sacred and secular, colonial and imperial meanings, and theserepresentations have played an essentially significant role in the self-representation of the post-war United States and its geocultural mission. While the Apollo lunar project signified the achievement of the technocratic goals and universalist rhetoricof Modernism, the project’s most enduring legacy is a collection of images whose meanings are contested in post-colonial andpostmodernist discourses.” Cosgrove. 270.6 N.A.S.A. estimates that fifty percent of the Earth’s surface is covered in clouds in this image: Image Science and AnalysisLaboratory, “The Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth,” Johnson Space Center, Houston http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/ mission AS17&roll 148&frame 22727 and http://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/FAQ/genEarth.htm and http://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/vis/a000000/a002680/ and NN (accessedFebruary 7, 2007).7 This image (titled Big Blue Marble, from Apollo 17) is labeled AS17-148-22727, from mission AS17, roll 148, frame 22727.8 Ibid.9 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981).10 Roland Barthes, Image, Music, Text (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977). 67.11 Marta Braun, “Time and Photography,” in Tempus Fugit: Time Flies, ed. Jan Schall (Kansas City, Mo.: Nelson-Atkins Museumof Art, 2000). 141. In this essay, Braun was commenting about the partial-Earth image Earthrise. Her thoughts are certainlyapplicable to Big Blue Marble, too.12 Charles Sanders Peirce, Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, ed. Charles Hartstone and Paul Weiss (Cambridge: HarvardUniversity Press, 1932). 267.13 Despite a flurry of excitement over the Apollo 17 mission, funding and interest in America’s space program have waned since1972. For more about the decline of interest in America’s space program, see: Cosgrove. 274.14 Batchen. 140.15 Stefanov.16 N.A.S.A. has called its digital composite photography of the Earth Big Blue Marble: Next Generation since around the year2000. It has been making digital composite whole-Earth images since the 1990s.17 In addition to N.A.S.A., these other organizations and companies also use ARC technology: the Russian Centre of CosmonautTraining, the Department of Defense, SPAWAR (Space and Naval Warfare Systems [U.S.A.]), UNAVCO (The UniversityNAVSTAR Consortium, [U.S.A.]), Raytheon, and Lockheed Martin. Customized versions of the software are also available, but ata higher cost. ARC also sells programs for making images of Mars, Jupiter, the moon, and for mapping the surface appearance ofthe Earth up to six-hundred-million years ago: “Face of the Earth,” ARC Science Simulations www.arcscience.com/face.htm andwww.arcscience.com/gallery.htm (accessed December 9, 2006).18 Ibid. N.A.S.A.’s Image Science and Analysis Laboratory uses a customized version of ARC’s software, laced together by its ownTHE INSTANT29

time implosiontechnicians with additional data from N.A.S.A.’s own eighteen satellites and additional staff-introduced modifications.19 For much more about the way that “decision trees” operate to simulate cloud cover, please see: Smadar Shiffman, “CloudDetection from Satellite Imagery: A Comparison of Expert-Generated and Automatically-Generated Decision Trees,” TheIntelligence Report (2005).20 ARC’s data is derived from the “NOAA TIROS satellite AVHRR data and colorized by a proprietary methodology patentedby ARC. It has continued to be enhanced by MODIS and Landsat derivatives.” ARC Science Simulations.21 Stephen L. Talbott, The Future Does Not Compute: Transcending the Machines in Our Midst (Sebsatopol: O’Reilly and Associates,Inc., 1995). 5.22 Barthes, Camera Lucida. 77.23 Ibid.24 Kimon Valaskakis, “The Concept of Informediation: A Framework for a Structural Interpretation of the Information Revolution,”in Information Technology: Impact on the Way of Life, ed. Liam Bannon, From the E.E.C. Conference on the Information Society,Dublin, Ireland, Nov. 18-20, 1981 (Dublin: Tycooly International Publishing Ltd., 1982). 33.25 Ibid. 31.26 Peter Galassi, Before Photography: Painting and the Invention of Photography (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1981). 19.27 Jonathan Crary, “Unbinding Vision,” October 68 (1994). 21.28 Jeffrey Sconce, Haunted Media: Electronic Presence from Telegraphy to Television (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000). 170171.29 He also argues that these binary collapses signal the end of “High Modernism” and “High Capitalism”: Frederic Jameson, “TheEnd of Temporality,” Critical Inquiry 29 (2003); Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham:Duke University Press, 1991).30 The employment of double-exposure, composite, collage, montage, and extended-exposure techniques in order to make an imageby manipulating and combining several separate pictures, was pioneered by John Herschel, Johann Carl Enslen, William HenryFox Talbot, Hippolyte Bayard, Édouard-Denis Baldus and Gustave LeGray in the nineteenth century, and was continued by OscarRejlander and Henry Peach Robinson, the Dada artists, and others through the twentieth century and up to today.31 Talbott. 9.32 Barthes. Camera Lucida. 115.33 Stefanov.34 Timothy Druckrey, ed., Electronic Culture: Technology and Visual Representation (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1996). 133.;See also: Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking About Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century(New York: Oxford University Press, 1988). 8.; Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge (U.K.): Polity Press, 2000).35 Dorthe Gert Simonse

Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey, the snapshots of Jacques-Henri Lartigue, the "decisive moments" of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the stroboscopic images of Dr. Harold Edgerton, and the 1960s snapshot aesthetic reflect and maintain this perception that the photograph captures the appearance of its subject in the fraction of a moment.