Transcription

National Association of Community Health CentersPartnerships between Federally QualifiedHealth Centers and Local Health Departmentsfor Engaging in the Development of aCommunity-Based System of CarePrepared by Feldesman Tucker Leifer Fidell LLP for the National Association of Community Health CentersOctober 2010

National Association of Community Health CentersAcknowledgments / DisclaimerThis publication was prepared for the NationalPartnerships between Federally Qualified HealthAssociation of Community Health Centers (NACHC)Centers and Local Health Departments for Engagingby attorneys with the law firm of Feldesman Tuckerin the Development of a Community-Based SystemLeifer Fidell LLP (FTLF). It is designed to provideof Care familiarizes the reader with federally quali-accurate and authoritative information in regardfied health centers and local health departmentsto the subject matter covered. While incorporatingand explores various collaborative models that op-certain principles of federal law, this guide is pub-timize resources and promote improved health carelished with the understanding that it does not con-access and quality improvement. While this guidestitute, and is not a substitute for, legal, financial ordoes not describe the full scope of partnership op-other professional advice. Further, this guide doestions, it provides guidance to support the reader’snot purport to provide advice based on specific stateefforts in evaluating, selecting, and implementinglaw. Federally qualified health centers and locala partnership that is appropriate for a particularhealth departments should consult knowledgeablecommunity.legal counsel and financial experts to structure andimplement a partnership that is legally, financially,and operationally appropriate given the particularfederally qualified health center’s and local healthdepartment’s respective goals, objectives, expectations, and resources.National Association of Community Health Centers2

Partnerships between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Local Health DepartmentsNational Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC)Established in 1971, NACHC serves as the national voice for America’s Health Centers and as an advocate for heath care accessfor the medically underserved and uninsured. NACHC’s mission is to promote the provision of high quality, comprehensive andaffordable health care that is coordinated, culturally and linguistically competent, and community directed for all medically underserved populations.National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO)NACCHO is the national nonprofit organization representing the approximately 2,860 local health departments (LHDs) nationwide, including members in all public health regions. NACCHO serves every LHD in the nation, without regard to the unit of government with which a department is associated. These include LHDs associated with counties; cities; combined county-city entities; towns; multi-town, multi-county, or other regional entities within a state; tribes; and states. NACCHO’s vision is health, equity,and well-being for all people in their communities through public health policies and services. NACCHO’s mission is to be a leader,catalyst, and voice for LHDs in order to ensure the conditions that promote health and equity, combat disease, and improve thequality and length of lives.For more information contact:Marcie Zakheim, Esq. orCarrie S. Bill, Esq.Feldesman Tucker Leifer Fidell LLP1129 20th Street, N.W.Fourth FloorWashington, DC 20036Telephone (202) 466-8960www.ftlf.comEmail: mzakheim@ftlf.com orcbill@ftlf.comKathy McNamara, RN, MANational Association of CommunityHealth Centers7200 Wisconsin AvenueSuite 210Bethesda, MD 20814Telephone (301) 347-0400www.nachc.comEmail: kmcnamara@nachc.comJennifer Joseph, PhD, MSEdNational Association of County and CityHealth Officials1100 17th Street, N.W.Seventh FloorWashington, DC 20036Telephone (202) 507-4237www.naccho.orgE-mail: jjoseph@naccho.orgxxxxxxxNACHC gratefully acknowledges Cindy Phillips, Lauren Shirey, Jennifer Joseph, Marisela Rodela, Reba Novich, and RobertPestronk of the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) for their invaluable collaboration on thedevelopment and writing of this guide. Additionally, NACHC thanks members of NACCHO’s HIV/STI Prevention and Access andIntegrated Services Workgroups for graciously sharing their knowledge of LHDs and providing editorial support.National Association of Community Health Centers3

Partnerships between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Local Health DepartmentsTable of ContentsIntroduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51 Federally Qualified Health Center-Local Health Department Partnerships: A Strategic Alliance. . . . . . . . . . 7Patient Protection and Affordable Care ActThe Patient-Centered Medical Home Model of CareMeaningful Use of Health Information TechnologyPartnership Benefits2 Defining Safety Net Providers: Federally Qualified Health Centers and Local Health Departments . . . . . . 13Federally Qualified Health Center FundamentalsDefining a Federally Qualified Health CenterKey Federally Qualified Health Center RequirementsCost-Based Reimbursement, Federal Tort Claims Act, Section 340B Drug Pricing, andAnti-Kickback Safe Harbor ProtectionFederally Qualified Health Center Scope of Project ConsiderationsLocal Health Department FundamentalsFunctionGovernanceFundingRelationship to State Health DepartmentJurisdictionsWorkforceServices3 The Planning Process: Laying the Foundation for a Successful Partnership. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37Essentials of a Successful PartnershipEstablishing a PartnershipQuestions to Guide the Planning ProcessConfidentiality AgreementHealth Information Exchange and Patient Privacy Considerations4 Federally Qualified Health Center-Local Health Department Partnership Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41Key Considerations and Agreement TermsReferral ArrangementsCo-Location ArrangementsPurchase of Services Arrangements5 Additional Legal Considerations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 536 Conclusion and Next Steps. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54Appendix A. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55National Association of Community Health Centers4

Partnerships between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Local Health DepartmentsIntroductionFederally qualified health centers (hereinafter “FQHCs”or Community Health Centers (“CHCs”)) and local heath departments (hereinafter “LHDs”) share a common mission to improve community health,particularly among vulnerable and underserved populations. FQHCs and LHDs currently work col-laboratively on behalf of their residents in many communities across the country.Today, the reasons for partnership between FQHCsFQHCs and LHDs differ in some substantive ways.and LHDs are particularly compelling. The passageFQHCs are charged with the delivery of a full con-of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Acttinuum of primary and preventive care services, and(the “health reform law”) signals an overhaul of theenabling services. LHDs are charged with popula-health care system, with an important emphasis ontion health, which may or may not include healthprimary care, prevention, and collaboration amongcare delivery. Likewise, as federally-funded enti-a community’s health care providers. A core com-ties, FQHCs structure and regulations are relativelyponent of the health reform law is the expansion ofuniform compared to LHDs, whose governance andthe patient centered medical home model of careactivities vary widely from state to state and fromdelivery, which calls for patient care to be coordi-community to community. However, the two entitiesnated and integrated across the health care system.are well positioned to be strong partners and thereBoth the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Actis a long history of coming together to improve bothand the expansion of the patient centered medicalindividual and population health.home model present fresh opportunities for healthPartnerships between Federally Qualified Healthand community leaders to work together to designCenters and Local Health Departments for Engag-and implement local health delivery and care sys-ing in the Development of a Community-Basedtems that:System of Care provides an overview of severalAddress the health issues of underserved andpartnership opportunities available to FQHCs andvulnerable communities;LHDs seeking to improve health outcomes in theirnImprove and document value;community, while promoting cost-effective care.nGenerate positive patient and community expe-Through the lens of partnership, LHD readers willriences of care and engagement in health; andbenefit from information presented about the keyImprove the health of target populations withfeatures of FQHCs and the various federal require-an emphasis on promoting health equity andments applicable to the program. Likewise, FQHCeliminating health disparities.readers will gain insight into LHDs.nnNational Association of Community Health Centers5

Partnerships between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Local Health DepartmentsSpecifically, this guide addresses:nThe Patient Protection and Affordable CareAct, the patient centered medical home modelof care, and the meaningful use of healthinformation technology as drivers in FQHCLHD partnerships;nBenefits associated with FQHC-LHD partnerships;nKey features of FQHCs and LHDs and theirrelevance to FQHC-LHD partnerships;nHealth information exchange and patientprivacy considerations within the context ofFQHC-LHD partnerships; andnVarious partnership models, including keyterms for written agreements to implement anaffiliation approach that is compliant with applicable FQHC federal rules and requirements.National Association of Community Health Centers6

Partnerships between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Local Health Departments1 Federally Qualified Health Center-LocalHealth Department Partnerships:A Strategic AlliancePartnerships are necessary to maximize resources, to reduce duplication of effort, and to improve quality, efficiency, and accessibility of health care services. The changing face of America’s underservedpopulation, the restricted resources under which FQHCs and LHDs operate, and the desire and needfor more fully-functioning and better prepared public health and primary care systems all demand a healthcare system based in local partnerships.address a variety of public health and primary careA. Patient Protection and AffordableCare Actpriorities, including but not limited to the following:The passage of the Patient Protection and AffordableCurrently, FQHCs and LHDs successfully partner tonHIV prevention and testing;Care Act (“the health reform law”) in 2010 providesnSTD testing, care and treatment;for a significant financial investment in programsnDental health;based in public health, primary care, and communi-nBehavioral health;ty collaboration. This investment reflects a nationalnChronic disease prevention;shift towards emphasizing wellness and prevention,nMaternal and child health; andclinical integration, and collaborative communitynEmergency preparedness.based care. Indeed, it is well settled that reform willnot be successful without such collaboration. Collab-NACHC and NACCHO: A Joint Mission to PromoteCollaboration between FQHCs and LHDsoration between FQHCs and LHDs is therefore notonly desirable, it is necessary given the priorities setOn June 1, 2010, the National Association of Com-forth in health reform.munity Health Centers (NACHC) and the NationalAssociation of County and City Health Officials (NAC-Health Reform and FQHC-LHD CollaborationCHO) collectively wrote a letter to their respectiveThrough collaboration, FQHCs and LHDs may posi-members, stating “NACCHO and NACHC recognizetion themselves to participate in funding opportuni-that a new collaboration between our two organi-ties. There are several relevant funding opportuni-zations can help our respective members addressties described in the health reform law, includingthe challenges of health system reform.” The letterthe following:further noted that excellent models of local collabo-nCommunity health teams (Pub. L. 111-148 §ration currently exist and that together the organi-3502): The health reform law states that healthzations plan to discover more models, to learn fromteams composed of community-based, interdis-them, and to encourage the development of suchciplinary medical professionals will be estab-constructive relationships nationwide.lished to support primary care medical homesNational Association of Community Health Centers7

1 Federally Qualified Health Center-Local Health Department Partnerships: A Strategic AllianceFrom Fragmentation to a HighPerformance Health Systemthat are within hospital areas served by thoseentities. This provision allows LHDs to receivefunds to establish a community health teamAccording to a Commonwealth Fund Commission on aand collaborate with local primary care provid-High Performance Health System report, fragmentationers, including FQHCs.nin the health care delivery system fosters frustrating andCommunity-based prevention and wellnessdangerous patient experiences, especially for patientsprograms (Pub. L. 111-148 § 4202): The healthobtaining care from multiple providers in a variety of set-reform law establishes that there will be grantstings. Fragmentation also leads to waste and duplication,for LHDs to carry out 5-year pilot programs tohindering providers’ ability to deliver high-quality, effi-provide public health community interventions.cient care.1 The Commission identified the following sixAmong other requirements, LHDs are requiredattributes of an ideal health care delivery system:to demonstrate the capacity to establish relationships with community-based clinical partn1. Patients’ clinically relevant information is availableners, such as FQHCs.to all providers at the point of care and to patientsPrimary care extension programs (Pub. L. 111-through electronic health record systems.148 § 5404): The health reform law authorizes2. Patient care is coordinated among multiple provid-grants to states to establish primary care ex-ers, and transitions across care settings are activelytension programs. These programs rely on themanaged.collaboration of LHDs and FQHCs to identify3. Providers (including nurses and other members ofcommunity health priorities and participate incare teams) both within and across settings have ac-community-based efforts to address these pri-countability to each other, review each other’s work,mary care priorities.and collaborate to reliably deliver high-quality, highvalue care.In addition to these opportunities presented in the4. Patients have easy access to appropriate care andhealth reform law, both the Centers for Diseaseinformation, including after hours; there are mul-Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Health Re-tiple points of entry to the system; and providerssources and Services Administration (HRSA) haveare culturally competent and responsive to patients’made public health and primary care collaborationneeds.a priority, resulting in the availability of funding to5. There is clear accountability for the total care of pa-support collaborative efforts.tients.6. The system is continuously innovating and learningin order to improve the quality, value, and patient experience of health care delivery.1National Association of Community Health Centers8Commonwealth Fund, Organizing the Health Care Delivery System for HighPerformance (2008).

1 Federally Qualified Health Center-Local Health Department Partnerships: A Strategic AllianceB. The Patient-Centered Medical HomeModel of Carefor Quality Assurance (NCQA) have created widely-The 2010 health reform law promotes delivery sys-supported standards for recognition as a PCMH.tem innovation and improvement through systemsNCQA’s Physician Practice Connections —Patientof care such as patient-centered medical homes andCentered Medical Home recognition program isaccountable care delivery models. Health reformbased upon meeting specific elements in nine stan-provides structure and incentives for providers todard categories. The Primary Care Development Cor-organize themselves and share savings under an ac-poration (PCDC) offers a How-To Manual for safetycountable care organization (ACO), deliver care vianet providers and organizations seeking to achievethe patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model,NCQA medical home recognition. Similarly, theand receive bundled and global payments for acuteAmerican College of Physicians (ACP) has developedand post-acute care.a Medical Home BuilderSM tool that provides step-by-Organizations such as the National CommitteeThe PCMH concept, originally introduced by thestep instructions, tools, and resources.American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in 1967, received further endorsement in 2007 when AAP, to-the Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered MedicalNCQA Physician PracticeConnections —Patient CenteredMedical Home RecognitionProgram2Home. Now widely accepted among medical orga-PPC-PCMH Recognition is based on meeting specific ele-nizations and associations, the prevailing medicalments included in nine standard categories:home concept is represented in the Joint Principles,1.which emphasize a patient’s ongoing relationship2. Patient Tracking and Registry Functionswith a personal physician, a whole person orienta-3.Care Managementtion, team approaches to care, care integration and4.Patient Self-Management and Supportcoordination, enhanced access, quality, safety, and5.Electronic Prescribingpayment for added value.gether with the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American College of Physicians (ACP),and American Osteopathic Association (AOA), issuedAccess and Communication6.Test TrackingAs one approach in a larger strategy to transform7.Referral Trackinghow health care is delivered in the United States, the8.Performance Reporting and ImprovementPCMH illuminates the role of primary care in con-9.Advanced Electronic Communicationtrolling costs, improving quality, and improving thepatient experience of care. This framework aims toNote: NCQA standards were recently open for public com-transform primary care practices in both the pub-ment; a proposal to collapse and reduce the categories fromlic and private sectors to ensure accessible, timely,nine to six is under consideration.comprehensive, patient-centered primary care andeffective coordination with other providers.2National Association of Community Health .

1 Federally Qualified Health Center-Local Health Department Partnerships: A Strategic Alliance“Yet as the United States seeks to optimize primary care, in part by advancing the concept ofthe ‘patient-centered medical home’ (PCMH), some of the key values of the CHC model—a wholeperson orientation, accessibility, affordability, high quality, and accountability—could well informtomorrow’s primary care paradigm for all Americans. Despite the challenges they face, the CHCsare already built on a premise resembling that of the PCMH, a holistic concept encompassing highly accessible, coordinated, and continuous team-driven delivery of primary care that relies on theuse of decision-support tools and ongoing quality measurement and improvement.”3Medical home initiatives within safety net popu-A National Demonstration Project by the American Acad-lations are in abundance, and FQHC engagement isemy of Family Physicians (AAFP) randomized 36 fam-on the rise. Over 40 FQHCs have already achievedily practice sites to facilitated versus self-directed groupsNCQA medical home recognition. According to thein implementation of the PCMH model. They foundNational Academy for State Health Policy, more thanthat transformation of practices required a tremendous35 state Medicaid agencies have legislated medicalamount of resources and external support. And whilehome initiatives, with many fully engaged in dem-greater adoption of medical home components was asso-onstrations, and the Medicare-Medicaid Advancedciated with improvement in measures of quality, preven-Primary Demonstration Initiative was announced intion and chronic disease care, patient ratings declined inSeptember 2009. The Safety Net Medical Home Ini-both the facilitated and self-directed groups during thistiative, a five-year demonstration launched in 2008transformation process. This evaluation reports that theby the Commonwealth Fund, Qualis Health, and the“jury is still out on the actual impact on quality of care andMacColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation, reliespatient outcomes .Realistically, it may require reform ofheavily on FQHCs as it seeks to produce a replicablethe larger delivery system, integrating primary care withnational model for implementing the PCMH in safe-the larger health care system, for the full impact of a PCMHty net primary care practices.implementation to result in statistically significant enhancements to most patient quality-of-care outcomes.”5A 2009 study by the Commonwealth Fund examinedFQHC capacity to function as a medical home based on3Health Care Reform and Primary Care — The Growing Importance of theCommunity Health Center, Eli Y. Adashi, MD, H. Jack Geiger, MD, and Michael D. Fine, MD. New England Journal of Medicine 362:2047-2050 (2010).4Enhancing the Capacity of Community Health Centers to Achieve HighPerformance, Findings from the 2009 Commonwealth Fund National Surveyof Federally Qualified Health Centers, Michelle M. Doty, Melinda K. Abrams,Susan E. Hernandez, Kristof Stremikis, and Anne C. Beal, May 2010.5Summary of the National Demonstration Project and Recommendationsfor the Patient-Centered Medical Home, Benjamin F. Crabtree, PhD, Paul A.Nutting, MD, MSPH, William L. Miller, MD, MA, Kurt C. Stange, MD, PhD,Elizabeth E. Stewart, PhD and Carlos Roberto Jaén, MD, PhD Annals of Family Medicine 8:S80-S90 (2010) doi: 10.1370/afm.1107.the presence or absence of five indicators developed fromthe National Committee for Quality Assurance’s medicalhome measures: Patient Tracking and Registry Functions;Test Tracking; Referral Tracking; Enhanced Access andCommunication; and Performance Reporting and Improvement. Twenty-nine percent of FQHCs had capacityin all five domains; 55% in 3-4 domains; and 16% in 0-2domains. A key opportunity for improvement is in care coordination across different settings of care.4National Association of Community Health Centers10

1 Federally Qualified Health Center-Local Health Department Partnerships: A Strategic AllianceWhile the health reform law is national in scope,technologies, particularly electronic health records,the task of implementing it and ultimately transform-that have the “capability to exchange key clinical in-ing the way health care is delivered in this countryformation (for example, problem list, medication list,will fall on state and local public health and primarymedication allergies, diagnostic test results), amongcare systems. Meaningful transformation will requireproviders of care and patient authorized entitiesan unprecedented level of cooperation and integra-electronically” to improve care coordination.7 Eligi-tion among various systems of health care delivery—ble professionals working in FQHCs and meeting theboth public and private. Furthermore, the PCMH or“30% needy individuals” patient volume thresholdhealth care home for underserved and vulnerablewill be required to demonstrate successful exchangepopulations must support and build individual effi-of clinical information by their second year of partic-cacy to maintain or improve health while providingipation in the Medicaid Incentive Program to receivea structure for community participation in the op-an incentive payment for that year. In subsequenteration of the health care home. Safety net practicesyears they will be required to have the ability to ex-should be engaged partners in a community healthchange this data on a regular basis.system that ensures access and coordination withThe rules also specify that eligible professionalsspecialty care, diagnostic services, public healthmay choose to have the “capability to submit elec-services, health information exchanges, hospitals,tronic syndromic surveillance data to public healthand other care settings as well as agencies and com-agencies and actual submission in accordance withmunity organizations providing social, education,applicable law and practice” and/or the “capabilityhousing, and other services necessary to maintainto submit electronic data to immunization registriesand improve health. For underserved and vulner-or immunization information systems and actualable patients, the health care home should functionsubmission according to applicable law and prac-as more of a village, requiring the transformationtice” as an element of meaningful use for purposesof the local primary care and public health systemsof qualifying for an incentive payment under theand strong leadership from within each.Incentive Program.8 These two options, along withthe capacity to submit electronic data on reportableC. Meaningful Use of Health InformationTechnologylab results to public health agencies (applicable onlyIt is essential that FQHCs and LHDs establish theproving population and public health.to hospitals), comprise the objectives aimed at im-ability to exchange information for the purposes ofFor more information regarding electroniccoordinating care for their shared patients and tohealth records and meaningful use, readers may re-provide the ability to improve population health. Thefer to the Department of Health and Human ServicesCenters for Medicare and Medicaid Services released(DHHS) website.its Final Rule on the Medicare and Medicaid Electronic Health Record Incentive Program on July 28,642 Fed. Reg. 44314, July 28, 2010.2010 in the Federal Register. These rules require742 Fed. Reg. 44360, July 28, 2010.that eligible professionals use health information842 Fed. Reg. 44367, July 28, 2010.6National Association of Community Health Centers11

1 Federally Qualified Health Center-Local Health Department Partnerships: A Strategic AllianceD. Partnership BenefitsClinical OutcomesThe potential benefits of FQHC-LHD partnershipsnextend beyond the four walls of the exam room andof risk factors, such as smoking.into the greater community. Partnerships put thenwell-being of a community into greater focus withnhealth outcomes, and decrease health disparities.nimmunizations, and nutrition; prevent mother-Enhance the capacity of community providersto-baby transmission of HIV; and decreaseto provide value, high quality, cost-effectivepremature birth and morbidity.medical homes for vulnerable populations.Assist low-income individuals to access the fullPublic Health Monitoringrange of safety net services and public benefitsnhealth assessments through collaboration andsubstance abuse counseling, Medicaid eligibil-sharing of surveillance and other population-ity, and other social services).based data.Generate more positive patient and communitynnand ultimately strengthening the existing safetynet delivery system.Reduce the need for more expensive in-patientand specialty care services as well as emergency room visits, resulting in significant savingsto a community’s health care system.Allow limited federal, state and local resourcesto be targeted and allocated to areas that mostrequire them.National Association of Community Health CentersFacilitate the partner notification process forHIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.Help to avoid the unnecessary duplication ofservices, lowering the costs of providing carenAllow providers to gather vital patient leveldata through disease registries.ResourcesnSupport comprehensive community publicavailable in the community (e.g., food stamps,experiences of care and engagement in health.nImprove access to prenatal care; educatewomen about well-baby care, childhoodSystems of CarenImprove immunization rates against vaccinepreventable diseases.Specifically, an FQHC-LHD partnership may:nReduce the spread of infectious disease in thecommunity.overall goals to improve access to care, improvenReduce chronic disease through the reduction12

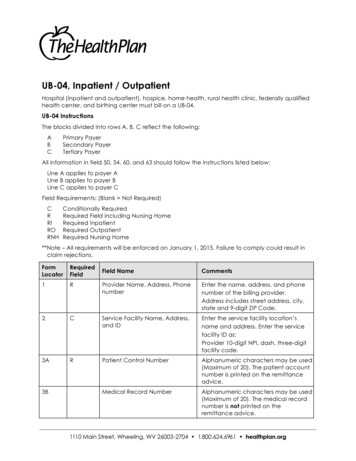

Partnerships between Federally Qualified Health Centers and Local Health Departments2 Defining Safety Net Providers: FederallyQualified Health Centers and LocalHealth DepartmentsFQHCs successfully overcome barriers to careA. Federally Qualified Health CenterFundamentalsbecause they are located in high-need areas; are1. Defining a Federally Qualified Health Centervices that facilitate access to care, such as outreachAn FQHC is a public or private non-profit, charita-and transportation; and tailor their services to theirble, tax-exempt organization that receives fundingpatients’ and their communities’ unique culturalunder Section 330 of the Public Health Service Actand health needs.12open to all residents of their service areas; offer ser-(Section 330), or is determined by the DepartmentFQHC patients are some of the nation’s mostof Health and Human Services (DHHS) to meet re-vulnerable individuals. Recent surveys indicate:13quirements to receive funding without actually re-nceiving a grant (i.e., an FQHC “lookalike”).97

partnership opportunities available to FQHCs and LHDs seeking to improve health outcomes in their community, while promoting cost-effective care. Through the lens of partnership, LHD readers will benefit from information presented about the key features of FQHCs and the various federal require-ments applicable to the program. Likewise, FQHC