Transcription

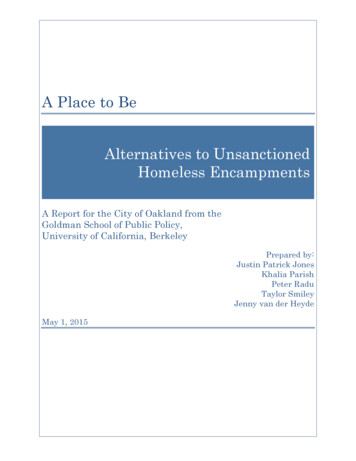

A Place to BeAlternatives to UnsanctionedHomeless EncampmentsA Report for the City of Oakland from theGoldman School of Public Policy,University of California, BerkeleyPrepared by:Justin Patrick JonesKhalia ParishPeter RaduTaylor SmileyJenny van der HeydeMay 1, 2015

Table of ContentsACKN OW LEDGEM EN TS . 4N AVIGATIN G TH IS REPORT . 5EXECU TIVE SU M M ARY . 6INTRODUCTION . 12PROJECT M OTIVATION . 13REPORT OU TLIN E . 14Research . commendationsandNextSteps.16Evaluative Criteria . tationFeasibility.17Analysis . 18OAKLAN D’S H OM ELESS EN CAM PM EN TS . 19Definition of “Encam pm ent” . 19Quantification of Oakland’s H om eless Population . 19Distribution and Characterization of Encam pm ents . .22Alam eda County Shelter and H ousing Resources . ty.22ShelterBedInventoryinAlamedaCounty.24Shortage of Affordable H ousing . 26Encam pm ent Abatem ent Expenditures and Activities . m pm ent Resident N eeds Assessm ent . tServicesPerspective.33STATU S QU O: Oakland’s Standard Operating Procedure .Stakeholder Perspectives on the Problem .Encam pm ent Cleanup Procedure .Obstacles to Im proving Outcom es .36363840ALTERN ATIVE #1: City-Sanctioned Encam pm ent . 44Case Study #1: Ontario, CA: Temporary Homeless Services Area . 45Overview.45EligibilityandServiceModel.451

easibilityConsiderations.47Case Study #2: Portland, OR: Dignity Village . dingandCosts.50Case Study #3: King County, W A: Tent Cities #3, #4, & Nickelsville . ityandConsiderations.55Design Feature Considerations for Sanctioned Encam pm ents . .63Summary.63ALTERN ATIVE #2: H ousing First Innovations . 66Case Study #1: Portland, OR . ns.68Case Study #2: N ashville, TN . tyConsiderations.71Case Study #3: Seattle, W A . sibility.76EVALU ATION OF ALTERN ATIVES . 79Analytic Fram ework . 79Oakland’s Status Quo – Current Costs of H om eless Encam pm ent Abatem ent. easibility:High.83Alternative #1: City-Sanctioned Cam pground . 842

plementationFeasibility:Medium/High.91Alternative #2: Am endm ents to H ousing First . h.97ImplementationFeasibility:Low.99RECOM M EN DATION S .Appendix 1: Interview Questions .Appendix 2: Home Forward’s Sources and U ses of Funding - FY2016 .Appendix 3: How’s Nashville Funding Sources .Appendix 4: Potential Sites for Pilot Sanctioned Encam pm ent in Oakland .102108109111112TABLE OF ofDecember2014).27Figure6.Encampment- dataasofMarch2015).30Figure11.CalTransfiscal- e.313

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe would like to thank the following individuals. Without their generous supportand time, this report would not have been possible.City of Oakland:Lt. Chris Bolton, Officer Doria Neff - Police DepartmentBrian Carthan - Parks DepartmentRachel Cole-Jansen, Tomika Perkins - Operation DignityJoe DeVries - City Administrator’s OfficeCasey Farmer - City Council, Councilmember Lynette McElhaney’s officeFrank Foster - Public WorksWendy Gorges, Wilma Lozada - Alameda County Trust ClinicSusan Shelton, Susan Katchee, Kennedy Solomon, Angela Pride - HumanServices Department Homeless Encampment ResidentsLocal and national organizations: Kathie Barkow - Alameda County Homeless Court Will Connelly - Nashville's Metro Homelessness Commission Kirby Davis - How's Nashville Bevan Dufty - San Francisco's Navigation Center Rachael Duke - Portland's HomeForward Rick Foot - Portland's Dignity Village Chris Herring - Doctoral candidate of Sociology at UC Berkeley Bill Hobson - 1811 Eastlake, Seattle’s Downtown Emergency Service Center Lucy Kasdin - Bay Area Community Services Heather Pollock - San Diego's Girls Think Tank Mark Putnam - King County's Committee to End Homelessness Robert Ratner - Housing, Alameda County Behavioral Health ServicesAgency Brent Schultz - Ontario's Housing and Municipal Services Judy Tackett - Nashville's Metro Homelessness Commission Residents of Oakland's homeless encampments4

NAVIGATING THIS REPORTThe breadth and depth of this report, while necessary for a meaningful analysis ofthe alternatives to Oakland’s unsanctioned encampment procedure, likely poses achallenge for those who are interested in a brief overview of the issue. The report isintentionally structured in such a way that readers are able to read just one sectionand still gain an understanding of the issue.For those who need a high-level overview, the Executive Summary (found on pages6-11) provides a broad summary of the following: Problem definition Key findings from analysis of the status quo Key findings from Alternative #1 research (city-sanctioned encampments) Key findings from Alternative #2 research (Housing First innovations) Recommendations Next StepsFor more detailed information about:The City’s motivation behind initiating the project, as well as the report’sresearch methodology and analysis, go to pages 13-18.The City’s status quo regarding standard operating procedures, stakeholdergoals, and the current characteristics of homeless encampments throughout theCity should visit pages 19-42.For best practices analysis regarding sanctioned homelessencampments and Housing First approaches please see pages 43-76. Thissection covers how jurisdictions across the country are responding to homelessencampments in their communities.The authors’ evaluation of the status quo against both alternatives canbe found on pages 77-99. This section outlines the criteria that the report’s authorsused to evaluate the status quo against possible policy alternatives as well as theevaluations themselves.Recommendations please see pages 100-105. This section describes short-,medium-, and long-term recommendations for the City to improve its currentapproach to unsanctioned homeless encampments.5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYIntroduction: The City of Oakland spends 9 million annually on homelessservices, yet an estimated 600-1,200 individuals sleep on the street on any givennight. Many of these individuals establish unsanctioned homeless encampments tosleep and store their belongings. As outlined by the City, the human health hazardsand blight associated with camps prompts residents’ complaints to city staff whichtriggers a cleanup. However, the status quo policy of continually sweeping camps isineffective as it (1) does nothing to address the root causes of homelessness and (2)is disruptive to homeless individuals attempting to access the pathway to housing.Problem Definition: The literature suggests that Housing First is not only themost effective, but also the only long-term solution to the problems associated withhomeless encampments and ultimately homelessness. However, creating affordablehousing is a challenge that the City of Oakland continues to face given rapidlyrising rent costs and a diminishing City budget. The City needs an interim solutionto address the needs of individuals living in homeless encampments while alsoreducing the City’s social and administrative burden of continually clearing andcleaning those camps.Approach and Methodology: In order to recommend alternative policies thatwould improve the status quo in Oakland, the authors performed a needsassessment of camp residents and city stakeholders, and analyzed best practice casestudies of two alternatives (1) city-sanctioned campgrounds and, (2) Housing Firstinnovations as they related to Oakland. Our best practices research informed ourconception and evaluation of each alternative in terms of its effectiveness atreducing the burden of perpetual cleanup on city staff, the equity of anticipateddistributional outcomes and finally, the feasibility of implementation.Key Research Findings:Status Quo: Oakland’s Standard Operating ProcedureThe analysis of the status quo consisted of interviewing City stakeholders on eachdepartment’s definition of the homeless encampment problem, strategies theycurrently use to address it, and the impact of these strategies on the homelesscamps and their occupants.One of the key takeaways is that city staff members have different perspectives onthe problem itself, which prompts departments to define success in solving theproblem quite differently. The diversity in perspectives is a product of eachdepartment engaging with homeless camps according to the overarching mission ofthat particular department. After clarifying the independent goals and duties ofeach department as they relate to homeless encampments, we found that these6

often contradictory approaches became problematic when one department’sdefinition of a successful outcome directly undermined another’s.This problem of the status quo undermining attempts of camp residents to get andstay on the pathway to housing became sufficiently clear throughout our needsassessment of the encampment residents. The needs assessment consisted ofmultiple interviews with outreach workers and a series of interviews with homelesscamp residents throughout the City, facilitated by Operation Dignity. The keytakeaway of these interviews is that these residents face serious barriers to bothhousing and shelter use that makes unsanctioned camps their only viablealternative. More importantly, despite best efforts of the City to coordinate withoutreach services and give ample notice to camp residents, the process of clearingcamps prevents residents from complying with important housing or healthappointments. In short, the status quo serves as a cyclical disruption forcamp residents and creates an additional barrier on their pathway tohousing.Alternative #1 – City-Sanctioned EncampmentThe report’s authors looked at three case studies to gain a better understanding ofthe motivation, design, and operation of sanctioned campgrounds on the WestCoast. These include Ontario, CA’s Temporary Homeless Services Area, PortlandOR’s Dignity Village, and three locations in King County, WA: Tent City #3, TentCity #4, and Nickelsville. The report also analyzes various design features that arecommonly found in sanctioned encampments; a description of each of theseconsiderations can be found on pages 56–64.The case studies vary in terms of the relative informal governance structures withincamps; some camps sprung from political protests while others are self-governed bypragmatic individuals seeking an alternative to shelters. They also differ in terms ofexternal involvement ranging from simple legal recognition to active serviceprovision.For the City of Ontario in San Bernardino County, CA, a unified and ongoingcommitment from City leadership was essential to getting the project off theground. Initially established in 2007, the encampment saw a rough period in termsof ballooning usage in its early years. Until very recently, the camp had stabilized toserving roughly 120 chronically homeless adults through a variety of local nonprofitand charitable groups; the camp closed last year after all but two of the residentsattained permanent housing.In Portland, Oregon, the camp Dignity Village initially grew out of a politicalprotest in 2000 and became formally established as a nonprofit the following year.Not until 2006 did Portland’s City Council sign a resolution designating the landthe camp had settled on as a formal campground, which now serves up to 607

individuals. Due to its distance from downtown Portland, the Village does not servechronically homeless individuals; as such, the average stay is 18 months. ThoughDignity Village is technically contracted with the City to manage the camp, thereare no City service providers on staff. Village residents are responsible for providinginternal security, with residents participating in the decision-making processgoverning the camp. As residents are required to pay 35 per month in rent, thecampground is also financially self-sustaining.Lastly, King County in the State of Washington has a number of sanctionedhomeless encampments that rotate every three months throughout the County andCity of Seattle. Developed in 2004, the policy ensures that a camp never stays atany one site, either private or public, for more than twice in a two-year period.Despite the transitory nature, community retention is high and the encampmentsconsistently meet their maximum capacity of 100 individuals. This approach reliesheavily on both strong internal governance by camp residents and engagement fromthe faith-based community, which often hosts the encampments.Alternative #2 – Housing First InnovationsThe report’s authors considered the Housing First approach as one of ouralternatives. The City of Oakland already has access to housing programs, chieflythe Permanent Access to Housing strategy (PATH). Therefore, we sought examplesof Housing First innovations that differ from Oakland’s current model. Our teamanalyzed three case studies: How’s Nashville in Nashville, TN; Home Forward inPortland, OR; and Downtown Emergency Services Center in Seattle, WA.The three case studies analyzed had several similarities. For example, each cityleveraged scattered-site units to house residents. These are apartments, typicallyrented from private market landlords, located throughout the jurisdiction of eachcity. The cities also all leveraged existing Federal funds to finance the expansion ofHousing First. In addition, each city employed a Vulnerability Index to prioritizewho would gain access to Housing First units, whether they be in scattered-siteunits or permanent supportive housing units. Two case studies, Portland andSeattle, included permanent supportive housing as part of their models. Finally,each city provides wraparound services to aid unsheltered residents in their effortto access housing.Portland’s Home Forward provides multiple programs for the people they serve.These include apartment assistance through low-income housing subsidized byHUD and managed by Home Forward; rental assistance, which consists of themanagement of Section 8 vouchers and their own programs to provide short-termrent assistance and support for veterans and renters with disabilities; and supportservices for recipients of Section 8 vouchers. Home Forward has also championed aLocal Blended Subsidy (LBS) Program, “to improve the financial viability of adding8

“banked” public housing units back into the portfolio.”1 They combine tenant-paidrent, Section 8 funds, and public housing funds to achieve total per-unit rent that iscompetitive with market rates.Home Forward also has a permanent supportive housing facility called Bud ClarkCommons, which determines eligibility through the administration of aVulnerability Index Tool by four medical clinics. The commons has an on-siteoperations team and case management that provide a number of supportive servicesincluding mental health, vocational rehabilitation, and money managementservices. When a resident no longer needs intensive supportive services, HomeForward staff work to support his/her applications to other public supportivehousing units in an effort to create space for the most vulnerable individuals at BudClark Commons. This program is reserved for individuals earning 80 percent orbelow of area median income and has supported 284 units to date.The How’s Nashville campaign is focused on ending veteran and chronichomelessness in Nashville, Tennessee. How’s Nashville, a play on “houseNashville,”

The authors' evaluation of the status quo against both alternatives can be found on pages 77-99. This section outlines the criteria that the report's authors used to evaluate the status quo against possible policy alternatives as well as the evaluations themselves. Recommendations please see pages 100-105. This section describes short-,