Transcription

FEATURES“Integrating contracting into intelligence,plans and operations can serve as a force multiplierin obtaining our campaign objectives.”—Gen. John R. Allen, U.S. Marine Corps“Counterinsurgency (COIN) Contracting Guidance”September 18, 2011OperationalContract SupportPlanning:Evolution to the Next LevelEmbedding operational contract support planning capability into each Army service componentcommand may be the key to filling contracting gaps in the current force structure. By Lt. Col. John M. CooperThe conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, along with smaller operations, took a littleknown and often overlooked Armysupport function and placed tremendous responsibility on its shoulders. Over the past decade, Armycontracting, along with its joint siblings, has played a more prominentrole in the way the Army plans andconducts military operations and logistics support.In 2007, more than half of U.S.personnel in Iraq were contractors.The proportion of contractors supporting U.S. forces in Afghanistanis nearly identical. The Army hasbecome reliant on contractors andthat reliance may grow as the Armydownsizes and stresses its alreadylean sustainment capabilities.Operational Contract SupportThe Army responded to the influxof contractors by establishing, growing, and maturing its contract management capability and implementing the operational contract support(OCS) concept within units. Whilethe OCS concept takes the Army inthe right direction, additional organizational solutions may be requiredto better integrate contract planning, build contracting as a core capability, and bridge the gap betweenthe supporter and the supported.The Army’s present force structure and approach to OCS continues to overlook significant capability gaps and key tasks at the broaderoperational level. The Defense Department’s Initial Capabilities DocMay–June 201317

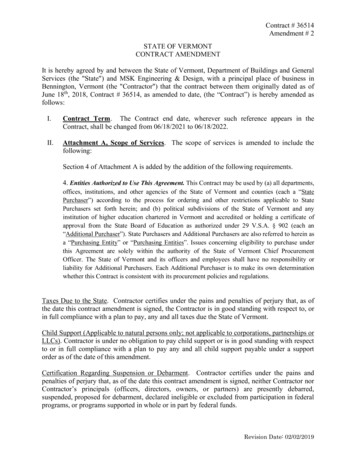

ument for Operational ContractSupport, dated July 19, 2011, provides a detailed list of OCS shortfalls above the tactical level. Included in that list are several operationalcapability gaps that the Army ischallenged to correct with the current force structure: A lack of OCS integration intocapability and task planning, operational assessments, force development, and lessons learned. A lack of synchronized OCSplanning across all operationalphases and among joint, multinational, and governmental andnongovernmental agency partners. Insufficient assessment of regional contract capacity, the extent ofexisting contracts, and commonuser contract support for keycommodities and services. A lack of centralized oversightto identify risk and recommendpolicies to control and monitorcontractors on the battlefield. Insufficient expertise among senior planning staffs to enablethe generation of synchronized,acquisition-ready requirementsdocuments. Insufficient awareness and appreciation of OCS significance andcomplexity, hampering the abilityto make full use of OCS in theoperational environment.Formal OCS ImplementationThe Army implemented OCS indoctrine, such as Army Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures 4–10, Operational Contract Support Tactics,Techniques, and Procedures, with astrong emphasis on execution at thetactical, rather than operational, level.One Army OCS solution includedcreating a non-acquisition force structure to support requiring-activityfunctions, such as developing contractrequirements, preparing performancework statements, and contracting officer representative management. Positions that perform those functionshave the additional skill identifier(ASI) 3C.18Army SustainmentSimilarly, military occupationalspecialty (MOS) 51C contingencycontracting officers (CCOs) aretasked to provide unit-level trainingand contracting support, execution,and management for the supportedelement. Despite education efforts,confusion lingers regarding the delineated roles and responsibilities ofASI 3C and MOS 51C personnel,indicating that OCS is not fully understood as a concept or task withinthe operational or acquisition communities.Regardless, this Army OCS solution focuses on tactical-level problemsassociated with the requirements development and contract managementphases of the contract life cycle. Although the solution has tremendousvalue in ensuring taxpayer dollars arewell spent, the current OCS conceptdoes little to address OCS-relatedplanning and effects at higher levels.Within the last 10 years, the Armycontracting community extracted itself from operational units to createseparate contracting organizations.That structure currently includes108 contingency contracting teams(CCTs) and 17 contingency contracting battalions (CCBNs) organizedprimarily to support tactical commanders at the division level andbelow. Seven contracting supportbrigades (CSBs) are committed totheater commanders and two additional rotational brigades are activating with alignment to corps headquarters.Contingency Contracting TeamsThe foundational unit for contracting is the CCT, which is chargedwith supporting maneuver and sustainment brigades, the division andcorps headquarters, and myriad otherunits operating within an assignedsupport area. The CCT comprisesfive CCOs awarding contracts underexplicit written authority.Most of the Army’s deployablecontract writing capacity resideswithin the CCTs. The team workshand in hand with the supportedunit’s ASI 3C-qualified personneland the supply or service end userthroughout the full life cycle of acontract, including requirementsdevelopment, training, monitoring,acceptance, and final payment.The CCT leader engages thesupported commander and staff tosynchronize and leverage contracting within operations. Early andconsistent involvement in the unit’splanning and execution cycle ensures contracting maintains a proactive, solution-oriented posture toenhance the commander’s mission.Ultimately, CCTs are concernedwith satisfying immediate requirements, contract management, andproviding tactical commanders withcritical tools to expedite urgent, lowcost requirements, such as the fieldordering officer program.Contingency Contracting BattalionsContracting’s initial level of command resides at the CCBN. Unlikethe CCTs, the 13-person CCBNs aremission command headquarters, notcontract-writing organizations. TheCCBN is generally aligned with asupported division, directing approximately six CCTs supporting the division area. A CCBN is also alignedwith each Army corps headquartersto provide equivalent command andcontrol to subordinate CCTs withinthe corps area.The CCBN implements, monitors, and assesses the effectivenessof higher-level contracting policiesand procedures, ultimately providingfeedback to commanders. Vested withgreater authority and responsibility,the CCBN commander reviews select solicitations and contracts to ensure compliance with policies, guidance, and service regulations.As contract administration ishistorically a high-risk and poorlyperformed task for the Army, theCCBN commander and staff provide critical contract managementoversight within the CCTs, ensuring contracting officers and unitrepresentatives are properly monitoring contractor performance, accepting supplies and services, and

OPERATIONALG–3ASCC HQs(Limited JTF HQs)CSTG–8 G–4 LOGCAPSJAHN REP(direct support)Contracting SupportBrigade (CSB)Theater-aligned(direct support)Contracting SupportBrigade (CSB)Corps-aligned(direct support)Contracting Battalion(Regional ContractingCenter)(direct support)Contingency ContractingTeams (RegionalContracting Offices)DLADCMAAFSBCorps HQs(primary JTF/JFLCC HQs)G–8 SJA G–4G–3Division HQsTACTICALG–3 CSB CdrBn CdrG–8 SJA G–4BCTS–3Tm LdrS–8 SJA S–4Sustainment BdeMANEUVER ANDSUSTAINMENTLegend:AFSBASCCBCTBdeBn CdrCSBCSTDCMAOPERATIONAL CONTRACTSUPPORT PLANNING Army field support brigade Army service component command Brigade combat team Brigade Battalion commander Contracting support brigades Contract support team Defense Contract Management AgencyTHEATER SUPPORTCONTRACTINGDLA Defense Logistics AgencyHN Rep Host nation representativeHQ HeadquartersJFLCC Joint forces land component commanderJTF Joint task forceLOGCAP Logistics Civil Augmentation ProgramSJA Staff judge advocateTm Ldr Team leaderFigure 1: Operational contract support from the tactical to operational levels.paying and closing contracts.Finally, the CCBN commandermust bridge many of the aforementioned capability gaps at the divisionlevel by directly engaging the division planning staff. This ensures thatcontracting is appropriately used andsynchronized within tactical plansand that contracting officers withinthe CCTs have sufficient warning toact quickly on emerging requirements.Contracting Support BrigadesThe next level of command isthe CSB, which can be either the-ater committed and aligned with anArmy service component command(ASCC) or rotational and alignedwith an Army corps headquarters.The CSB commander typicallyserves as the senior contracting official within a theater or Army corpsarea and, as such, the 24-personCSB’s primary functions include thefollowing: Plan and execute contract support for a supported theater orcommand. Establish and maintain contractingpolicies, procedures, and prioritiesto support operational objectives. Train, develop, and warrant contracting officers. Ensure contracts and other transactions comply with applicablepolicies, regulations, and public law.The CSB also provides missioncommand to subordinate CCBNsand CCTs as well as to joint contracting partners when the Armyis designated as the lead service forcontracting during an operation.Like their subordinate leaders,CSB commanders must engage withMay–June 201319

supported commanders and staffs.Understandably, consistent involvement in operational planning withany level of detail becomes a significant challenge at senior levels wheremission complexity and the numberof supported units increase dramatically. The CSB, particularly a theatercommitted organization, can quicklybecome overtaxed, lacking sufficientdepth to provide dedicated planningassistance to senior headquarters.An Organizational SolutionThe Army requires a more robustorganizational evolution to addressthe identified capability gaps. Sufficient structure presently exists at thetactical level to provide sound OCSsupport and planning assistance to division and brigade staffs. Even withinthe Army corps area, there is sufficient redundancy among the CSB,CCBN, and CCT to enable OCS engagement for major units, such as theexpeditionary sustainment command.However, OCS capability erodesconsiderably at echelons abovecorps, where significant operationalplanning occurs, particularly withG–1:RSOI; ContractorAccountability;MailG–2:Intel; ContractorBackground;Checks; CIG–3:AT/FP; ContractorArming; TrainingJARB; SecurityMortuary G–8/FM:Budget & FiscalManagementDisbursingSJA:Contract/FiscalLaw; ContractorUCMJDCMA:External & SystemSupport ContractAdminLOGCAP:Contracted LogAugmentationDLA:CoordinatedAcquisitions (Class I,III, V, Water, etc.)AFSB:Strategic Log Spt;Prepo Stocks;Depot Maint.G–4:Logistics RequirementsPlanning; Trans &SustainmentG–5:Effects; Plans;Contraints; RiskAnalysisG–6:FrequencyManagement; ITSecurityrespect to the development of theater-unique contingency plans, crisisaction plans, and shaping or theatersecurity cooperation missions. Thisdecreased capability directly correlates to the six identified capabilitygaps; therefore, a solution is requiredto resolve gaps and capability shortfalls within the ASCC.The Army should develop, activate, and resource a contract supportteam (CST) comprising three experienced contracting officers withineach ASCC headquarters. Thisteam would be assigned to a corre-Surgeon:Treat/Evac Injured;DBA sificationMP/CID:Fraud & Crime;Trafficking al ArmyCommandsTypicalParticipantExternal Legend:AT/FP Antiterrorism/force protectionCI CounterintelligenceDBA Defense Base ActFM Financial managementIT Information technologyJARB Joint acquisition review boardPAO:Convey the OCSMessageKM:OCS CommonOperating PictureKM Knowledge managementMP/CID Military Police/Criminal Investigation CommandOCS Operational contract supportPAO Public affairs officeRSOI Reception, staging, onward movement, and integrationUCMJ Uniform Code of Military JusticeFigure 2: OCS planning team and staff responsibilities and interaction. (Image courtesy of retired Army Lt. Col. George Holland)20Army Sustainment

sponding CSB, which would allowthe team to maintain a strong linkto the contracting community andwould permit the CSB commanderto select the best-qualified officersfor this assignment.A three-person team would facilitate 24-hour contingency operations, with a senior field grade officer and senior noncommissionedofficer during the day shift and acompany grade officer monitoringactivity during the night shift.The team would become an integral part of the supported commander’s headquarters, but its placement within that headquarters maybe unconventional to many. Thecontracting function is historicallyassociated with the G–4 sectionsince it is considered a logistics enabler, particularly at the tactical level. However, placing the OCS planning team within the ASCC G–4may not be the ideal solution.Each staff section has some contracting equities and bears some responsibility for indoctrinating, managing, providing for, and interactingwith contractors. Aligning the teamwithin the G–3/5 rather than theG–4 provides the best vantage pointfor emerging operations as desiredend states, branches, sequels, andrequirements are developed. Ultimately, this allows the team to coordinate with other planners andeliminates functional stovepipes andsituations where contracting is simply used to manage incomplete oruntimely requirements.The CST focuses on theater-wide,macro-level contracting issues, rather than tactical, micro-level contracting issues executed by CCTor CCBN leaders at the brigade ordivision level. The CST’s missionis not to write or directly managecontracts. Instead, the team concentrates on six fundamental tasks: Establish a foothold within theASCC planning staff to foster relationships and educate the supported organization. Actively participate in the ASCC’splanning process to leverage andintegrate contracting, guide decision making, develop planningdocuments, and conduct OCSrelated intelligence preparation ofthe operational environment. Develop contracting policies andprocedures to enable the commander’s mission. Act as the common link for various contracting activities withinthe theater. Identify operational problems anddevelop comprehensive contractedand noncontracted solutions. Articulate contract-related riskand develop mitigation strategies.While the CST assists in plan development and addresses operationalconcerns at higher levels, the CCBNand CCT perform similar functionsand provide technical advice locallyto their supported commanders.This leads to the desired end state,with contracting collectively assessing operation feasibility, guiding decision making, and proactively finding solutions at all levels to supportthe commander’s mission.The Six Tasks of the CSTLet us further explore the CST’ssix fundamental tasks.Establish a foothold within theASCC planning staff. The CST’sfirst task is to establish itself withinthe ASCC planning staff to enablehabitual interaction and greater education regarding contracting capabilities and challenges.Presently, the ASCC staffs haveinsufficient OCS expertise and thealigned CSB is not sufficiently resourced to accommodate suddenactivation and deployment of a contingency command post. Should amajor contingency event occur, therewould be a delay while the Armycontracting community identified,organized, and placed experienced,capable contracting personnel in theoperational headquarters.This occurred in Iraq, where contract planning was only marginaluntil the ad hoc Joint ContractingCommand–Iraq/Afghanistan (JCC–I/A) was created, contracting unityof effort was established, and CCOsbegan engaging the various headquarters. Pre-positioning a CST withineach ASCC eliminates any delays, establishes relationships, and overcomesthe aforementioned capability gaps.Actively participate in the ASCC’splanning process. The CST’s nexttask is to actively participate in operational planning. This enables theteam to guide decision making, identify shortfalls early in the planningcycle, assist in developing appropriate contracted and noncontractedsolutions, and then provide key intelligence to contracting leaders, enabling them to complete preparatorywork to reduce acquisition lead times.Active participation is particularlycritical when operations drive major acquisitions, such as establishingforward operating bases. This was achallenge during the Iraq surge whenJCC–I/A and the Logistics CivilAugmentation Program (LOGCAP)played critical roles. Contractingmaintained a position on the fringeof operational planning, resulting insuboptimal advance notice, synchronization, and operational input.Embedding the CST overcomesthat challenge while permitting routine preplanning for region-specificcontingencies, assessing local supplyand service capabilities, and planninghow to best employ high-demand,low-density contracting personnel.Develop contracting policies andprocedures. In some cases, the solution to an operational problem maybe a change in policies or procedures. In coordination with the CSBcommander and staff, the CST assists and guides the supported commander in establishing commandspecific, contracting-related policiesand procedures. The team providessubject-matter expertise to ensurethose policies and procedures comply with acquisition regulations, donot conflict with CSB policies, support the operational end state, andare executable by CCOs in the field.As an example, JCC–I/A andMulti-National Force–Iraq impleMay–June 201321

mented the Iraqi First program aspolicy, directing CCOs to give preference to Iraqi-owned businesses asa way of achieving the operationalobjective of improving local-national employment and reducing foreignbusiness intrusion.Alternatively, establishing acquisition boards, such as the Joint Acquisition Review Board, is a procedural option to ensure requirementsare actionable, properly staffed andprioritized, and possibly consolidated to benefit from economies ofscale.Act as the common link for various contracting activities within thetheater. The CST also serves as theheadquarters’ common link to external organizations and LOGCAPpersonnel to ensure that requirements and contract support are synchronized, feasible, and suitable.External contracting activities mightinclude the CSB, Army field supportbrigade, Defense Contract Management Agency, and Defense LogisticsAgency. Host-nation civil or militaryrepresentatives may also be consulted regarding acquisition and crossservicing agreement options. Ultimately, the CST acts as the hub forsynchronizing the contracting effort.Identify operational problems anddevelop comprehensive solutions.After identifying an operationalproblem and building relationshipsamong stakeholders, the CST canexecute its next task of developingcomprehensive contracted and noncontracted solutions. Positioned asthe command’s link to external contracting enablers, the team expandsthe number of options for the supported commander.Deploying military sustainment oliticalDecisive PointNodeLinkFigure 3: Political, military, economic, social, information, and infrastructure system analysis.(Joint Publication 5–0, Joint Operation Planning)22Army Sustainmentengineer assets may be a more timelyand cost-effective noncontracted solution for a short-duration mission.Activating LOGCAP to manage aseaport or to provide longer-term lifesupport for U.S. forces may be a viable contracted option using U.S.or third-country nationals. WhileLOGCAP may be one solution forreasons of scale, scope, or complexity,deployed CCTs may be able to execute similar contracts using local nationals to achieve the same support,but with different operational effects.The team can also tap into capabilities outside of the theater, such as theArmy Materiel Command’s Rock Island Contracting Center, which provides reach back support to purchaseurgently required supplies for contingencies from the United States. Likewise, the General Services Administration, Defense Logistics Agency,Army Corps of Engineers, and others maintain a contingency responsecapability. Fostering effective multiagency communication to find suitable solutions to operational problemsis an essential team function.Articulate contract-related risk anddevelop mitigation strategies. Finally,regardless of the environment or mission, the CST identifies, assesses, andplans to mitigate contract-related riskat the operational level. Contract-related risk is associated with a suddeninflux of U.S. military buying powerin an immature or austere marketplace. This influx can lead to a falseeconomy, cause rampant inflation,and create an economic dependencyon U.S. spending—each of whichcan have a catastrophic impact on thelocal populace and the host-nationeconomy.Another risk is that funds used topay contracts will be channeled tofund insurgent or terrorist activity.This risk is especially high wherecash is the primary payment method,as was the case in Iraq. A large contract workload, poor oversight, andhigh cash flow contribute to increases in fraud, corruption, collusion, andorganized crime, which must all bemitigated during planning.

Even currency selection for contract payments carries risk since using U.S. dollars exclusively may irreparably devalue a local currency.Risk will vary with every operation,but it must be balanced with potential outcomes or payoffs. Ultimately,the CST must consider contract-related risks and integrate mitigationstrategies into plans, policies, andprocedures.Employment on the BattlefieldThe collective effort of the commander’s planning staff and an actively engaged CST performing itskey tasks has the potential to positively influence the tactical and operational environments. The teamremains involved throughout allphases of an operation to enable various lines of effort, creating positiveeffects to achieve desired outcomes.On the battlefield, minor changesto the economic system can and willinfluence the political, social, military, infrastructure, and other systems. The CST must understand thesecondary and tertiary effects of eachdecision along the economic lines ofeffort in order to develop plans, policies, and procedures that enable contracting to help shape the environment, rather than fall victim to it.Decisions made at all levels willinfluence the operational environment. All CCOs, not just the CST,must understand that contracting’sinfluence goes beyond fulfilling ashort-term requirement, particularlywhen a contract does not support oris actually counter to the operationalend state. A simple decision to hirea small group of third-country nationals for a janitorial contract fulfills a unit’s requirement, but it doesso by possibly displacing employablelocal nationals.While that single contract mayhave been negligible, the social andpolitical systems can be affected,particularly at the local level. Accordingly, the CST must considerthe tactical and operational environment and take a “whole of government” approach, whether planningoperations on the Joint Task Forcestaff or considering contracting policies or procedures at the CCT level.OCS Tasks by PhaseThe assorted OCS tasks, effects,and focus will vary with the different phases of an operation, whichare described in Joint Publication(JP) 3–0, Joint Operations. During Phase 0 (shape), the militaryfocuses on theater campaign andcontingency planning. OCS planners strive to identify contractingshortfalls as plans are developed,assess marketplace capabilitiesthroughout the region, and ensurecontracting force structure is included in the early and overall deployment plan.Additionally, Phase 0 is the military’s opportunity to improve multinational relationships, interoperability, and cooperation amongforeign partners and allies. Thisis accomplished, in part, throughrecurring multinational exercises,such as Cobra Gold, and commandpost exercises, such as Yama Sakura. Contracting personnel are heavily involved in these events, spanning the tactical-to-operationalrange, providing critical planninginput, and executing contract support on the ground.As the operation moves intoPhases I through III (deter, seizeinitiative, and dominate), the CSTstrives to enable combat operations.The team continues to engage theplanning staff as various plans areupdated, implemented, and executed. While monitoring current operations, the team focuses on planning future operations.Accordingly, the CST examineseach branch and sequel to determine how and where to leveragecontracting to support and enablemission accomplishment. While theCST fulfills its mission at the operational level, most CCT personnelat the division-level and below perform “muddy boots” contracting,fulfilling urgent requirements tosupport reception, staging, onwardmovement, integration, other sustainment functions, and maneuver.With the transition to Phases IVand V (stabilize and enable civil authority) and the curtailment of sustained combat operations, the CSTfocuses on long-term tasks and effects along the economic lines of effort. The team continues to providekey inputs to the planning process,identifies contracting requirementsearly on, and liaises between thesupported commander and contracting stakeholders.In conjunction with the CSBcommander, the team also assistsin formulating long-term policiesand procedures to improve the operational environment. Meanwhile,tactical-level contracting personnelimplement CSB and ASCC policies and procedures locally whilecontinuing to fulfill sustainment,reconstruction, and redeploymentrequirements.Creating Favorable EffectsAlong with phase-specific tasks,the CST continues to be involvedacross the spectrum of conflict andrange of military operations to create favorable operational effects. AsJP 3–0 explains, the range varieswith the size, purpose, and intensity of the operation.At one end of the spectrum areshaping operations and activities,such as military-to-military engagements, civil assistance projects, and theater security cooperation programs. Toward the centerof the spectrum lie crisis responseand small-scale, limited-durationcontingencies. At the far end of thespectrum are major combat operations and campaigns generally associated with declared war.Within the range of military operations are two types of missionsfor which contracting is well-suitedto create favorable operational effects, particularly with early andactive CST engagement: stability/counterinsurgency (COIN) and humanitarian assistance/disaster relief(HA/DR).May–June 201323

Stability/COIN MissionsIraq and Afghanistan are familiar examples of the stability/COINenvironment. The increased forcepresence during the surge was instrumental in stabilizing Iraq; however, contracting also played a rolein the overall success by engagingMulti-National Force–Iraq leaders and mirroring the CST’s dutieswithin the ASCC. Analyzing thesituation in Iraq helped identify rootcauses of the insurgency, such aslarge-scale unemployment.Senior leaders within the operational and contracting commandsthen developed strategies to treat thedisease, rather than symptoms, of theinsurgency. The result was the Money as a Weapons System manual andthe Iraqi First policy. These innovative concepts used contracting to target an economic problem with clearsocial and political repercussions.JCC–I/A implemented policiesand procedures to achieve favorableOCS effects, such as increasing Iraqiemployment and injecting capitalbuilding funds into the economy,so as to enable the maneuver commander’s stability/COIN strategyand end state. JCC–I/A restrictedcompetition and gave preference toIraqi businesses, thereby increasingcontracting opportunities for thoseentities while decreasing intrusion byKuwaiti, Turkish, or U.S. businessesoperating within or adjacent to Iraq.To build Iraqi businesses, JCC–I/A and the civil-military operations centers hosted business development seminars, required vendorregistration, mentored business owners, and engaged local leaders toencourage participation in the contracting process.Using Iraqi businesses to fulfillU.S. and host-nation requirementsincreased Iraqi employment directlyand indirectly, improved the nation’sgross domestic product and currency,reduced U.S. and third-country national presence, and stabilized wages.In the end, properly developed andemployed OCS effects helped tomarginalize the insurgents’ influ-24Army Sustainmentence, improve Iraq’s domestic security, and enable the transition to alegitimate Iraqi government.HA/DR MissionsThe CST’s approach to an international HA/DR environment maybe considerably different. Stability/COIN OCS assets strive to bolsterthe economy through contracts withlocal businesses, but comparableHA/DR assets may prefer to avoidlocal purchases.CCOs tend to deploy as far forwardas possible to work directly with thesupported unit. This can be counterproductive in a decimated or austeremarketplace incapable of supportingU.S. demand or where U.S. forces arevying for the same critical commodities and services as the impoverishedcivilian populace, the host-nationgovernment, or relief agencies.For example, during the 2010Haiti earthquake response, forwarddeployed CCOs quickly learned thatfew supplies or services were available in Port-au-Prince and that thelimited quantities that did exist werein high demand. Because of the operational en

Formal OCS Implementation The Army implemented OCS in doctrine, such as Army Tactics, Tech - niques, and Procedures 4-10, Op-erational Contract Support Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures, with a strong emphasis on execution at the tactical, rather than operational, level. One Army OCS solution included creating a non-acquisition force struc-