Transcription

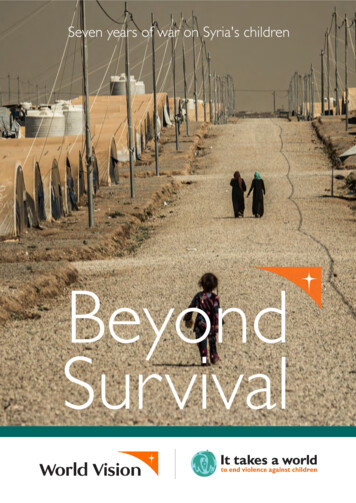

Seven years of war on Syria's childrenBeyondSurvival

?It's notenough tolive. You haveto be allowedto DREAM.?Virginia Gamba,Special Representativeof the UN SecretaryGeneral for Childrenand Armed Conflict,Global Partnership toEnd Violence againstChildren, SolutionsSummit February2018World Vision is a global Christian relief, development and advocacy organisation dedicated to workingwith children, families and communities to overcome poverty and injustice. World Vision serves all people,regardless of religion, race, ethnicity or gender. World Vision International 2018All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any form, except for briefexcerpts in reviews, without prior permission of the publisher.Published by World Vision Middle East and Eastern European Regional Office on behalf of the WorldVision Syria Crisis Response team and World Vision International.

SURVIVINGChildren in Syria live under the constant threat ofviolence. The blatant flouting of internationalhumanitarian (IHL) and human rights law (IHRL)has earned this crisis the dubious honour of beingrecognised as the most significant humanitarianprotection crisis in living memory.1 Over 13million people are in need of humanitarianassistance inside Syria, with deepeningvulnerability disproportionately affectingchildren.2 Conflict contexts, by their very nature,are crises of humanitarian protection, however,the brutality and indiscriminate actions by warringparties within Syria, are exceptional.In February 2018, World Vision spoke to 1,254Syrian girls and boys in Southern Syria, Jordan andLebanon.3 They talked about their daily lives, theirhopes for the future and the things they thinkabout. Their stories included war-inducedviolence, displacement, and missing, separatedand deceased family members. They also talkedabout home and their eagerness to restore theirlives as they once were. All were stories of dailystruggle that showed hardships that thesechildren face yet cannot change on their own.Together, the children described material andsocial stressors that range from situations ofviolence to daily struggles for basic services4:conflict-induced violence, violence fromcaregivers, unsafe and overcrowded livingconditions, working to support their families, andfinally, poverty and isolation that limit access tosystems of protection, education, health care, andeven water. One quarter of the children namedfour or more stressors in their lives. Theaccumulation and combination of these stressorscontribute to life-altering and long-termconsequences for children who have alreadyendured years of violence, poverty and precariousliving conditions.5The children and youth of Syria have becomecollateral damage in a situation beyond theircontrol. The scale and continuity of violence, theyears of living in or under the threat of militaryaction, the loss of life, livelihoods, infrastructureand the risk of physical injury warrant immediateand uncompromising child protectioninterventions. This is not only about protectinglives, but also about protecting childhoods andchildren?s ability to become healthy andfunctioning adults in the future.The international humanitarian communitystruggles year on year to meet the mountingneeds as insecurity, lack of humanitarian access,gross violations of international law and a lack ofpolitical will exacerbate the complexity and scaleof suffering. As each year passes, children?sexposure to violence, exploitation and adoptionof negative coping mechanisms for survivalescalates.For children exposed to warfare and other typesof violence, stressors can have a significant effecton mental health including Post Traumatic StressDisorder (PTSD), toxic stress, depression,anxiety, and reduced levels of resilience.The severity and increasing number of stressors,if unaddressed, increase the likelihood thatIn February 2018, World Vision asked 1,254 of Syrianchildren, ages 11 to 17 (629 boys and 625 girls), living insideSouthern Syria and in refugee camps and host communitiesin Lebanon and Jordan about their daily lives.The research team held 409 interviews in Southern Syria,378 interviews in Jordan and 467 interviews in Lebanon.The survey is a purposive sample that is a non-representativesubset of the larger population of refugees in Jordan andLebanon and displaced persons inside Syria. The sample isconstructed to show that children are experiencing multiplestressors in the settings where they live.-3-

children will experience mental illness, longerterm health effects such as heart disease andstrokes, diminished coping abilities, violence andlife-long poverty in their lives.6If the number and severity of daily stressors canbe reduced, the potential long-term effects ofexposure to violence can be mitigated. Reducingdaily stressors strengthens coping mechanisms,builds back resiliency and sets a positive coursetowards recovery. Because stressors can besevere (violence) and/or chronic (daily, ongoing)and range from a lack of access to water, foodor medical treatment to acts of violence, thespectrum of programmes and interventionsneeded to reduce, mitigate and prevent stressorsmust also be broad.7Children and families need programmes thatpromote their resilience and increase copingmechanisms to mitigate the effects of stressors.Expansion and investment in mental health andpsychosocial support programmes (MHPSS) isurgently required.These programmes have shown to reduce levelsof stress, insecurity, emotional and behaviourdifficulty and protect childhood developmenttrajectories.8 Moreover, mental health andpsychosocial support programmes can strengthensocial support networks that enhance trust andtolerance among children and youth, help todevelop reconciliation, enable children to becomeactive agents of change in their communities andrestore hope.Families and children need systems andprogrammes that prevent violence and protectchildren from violence at the community andfamily level. Violence in the home, at school andin communities are stressors that require asystems approach; formal and informal actors andservices that offer reporting, referral andresponse mechanisms are essential. Programmesthat change attitudes and behaviours, offer copingmechanisms and build the resilience of caregiversare also needed.AHMAD'S STORY'Our home was completely destroyed; my motherwas killed and my brother was detained by one ofthe armed groups. They forced us to leave ourvillage. We left immediately as we no longer had ahome there. I remember that it took us threemonths to arrive into Southern Syria.'At 14-years-old, Ahmad* has already witnessedunspeakable violence and lives with hardship on adaily basis. He left his family village four years agoto travel to Southern Syria after surviving fouryears of ongoing conflict.'I don?t want to drop out of school. I am feeling abit behind in my schoolwork because I don?t havethe space to study and get the right support.My father, my six siblings and I are living in thesame room. Despite the constant fear ofairstrikes, I try to spend my own time playingoutside with my friends.'Like any child, Ahmad has dreams. He wants tosee the end of conflict, a return to normal lifeand hopes to be an engineer someday. 'My cousinshave left Syria. I miss them so much. I miss mybrother too. I hope one day we can all returnback to our village and build a bigger house foreveryone! I want to feel happy most of the time.I wish we had more money to buy enough foodfor us and a TV to watch my favourite show' headded.*Name has been changed to protect identity.

STORIES OFSURVIVALComplex and dire, Syria?s conflict rages into itseighth year. Warfare across the country has forcedover five million Syrians to flee the country, half ofthem children and another six million to leave theirhomes in search of safer spaces inside Syria.9In February 2018, World Vision asked 1,254 Syrianchildren, ages 11 to 17 (629 boys and 625 girls), livinginside Southern Syria and in refugee camps and hostcommunities in Lebanon and Jordan about their dailylives.10 The results reveal a fragment of the conflict?schallenges that need to be addressed by hostgovernments, donors and political actors yetdescribe some of the biggest issues that Syria?schildren face living in the midst of the region?sconflict.The survey shows that the conflict has dramaticallyaltered children?s familiar living environments andsocial structures.11 They have moved to new places,live in confined spaces, attend different schools, andmiss family members and friends who were oncepart of their lives. Talking to World Vision staff andpartners, eleven-year-olds Kareem* and Rania* spokeof their hope to be reunited with friends and familyfrom whom they are now separated. Eleven-year-oldMona* and sixteen-year-old Mariam* spoke aboutthe fear of air strikes and warfare. Sixteen-year-oldLeila* spoke of her family?s poverty andfourteen-year-old Nadar* shared his dream to returnto school. However, by far, the most referencedresponse focused on Syria?s protracted conflict.Children also referenced the condition ofdisplacement or exile as a negative experience intheir lives. Their stories suggest that they intrinsicallyaccept daily stressors they experience as part of lifeas a refugee or displaced person. Children identifiedtheir chronic daily hardships as merely part of livingas a refugee or displaced person.

Percentage of children surveyed who referenced the following experiences as negative:65%JordanSouthern SyriaLiving in exile23% 23%PovertyConflict unendingLiving indisplacementLiving inexile19%30% 30%Family separation20%UnpredictablefutureConflict unending33%Conflict unending51%LebanonThe survey is not illustrative of country-wide statistics and does not represent populations outside of the survey areas.LAMIA'S STORYinterventions that included counselling with afocus on issues and rights that were affectingLamia. After three months, Lamia started takingpart in all the activities. She joined computer andart classes, built friendships and favoured groupactivities over other individual choices forlearning and skill building. The instructors noticedthat Lamia finally allowed herself to enjoy andengage in activities that were right for her agegroup and level of development.Fifteen-year-old Lamia, is the eldest child in hersingle-parent household. After her father left hermother and two younger brothers to fend forthemselves, she has had to take on more familyresponsibilities.Her family relies on donations and assistance toput food on the table and cover a month?s rent.Her mother asked Lamia and her brothers totake jobs after school during the months wherefinances were short.After Lamia enrolled in one of World Vision?sChild Friendly Spaces as part of the NOURProject, the instructors noticed that Lamia didnot participate in any of the group activities.When asked why, Lamia replied, ?I?m a grown-up,I?m not a child like the rest of these people. I havemore important things to do than to play around.?The instructor introduced psychosocial support-6-'I used t o t hink t hat I couldn't play or laugh,but now I'm convinced t hat I can. N ow Iunder st and t hat at my age, t hat is what Ishould be doing. I'm a com plet ely differentper son aft er t aking par t in t he childfr iendly space. It t r uly is t he light in my life.'Lam iaNour means light in Arabic. The NOUR project inJordan is funded by The Government of Canada.

VIOLENCEEDUCATIONChildren naming at least one EDUCATIONRELATED STRESSOR such as violent discipline,bullying and difficulty of curriculum.99%PHYSICAL or SEVERE VERBALVIOLENCE AT HOME50%86%52%SouthernSyria15%Southern SyriaJordanLebanonJordan39%LebanonCHILD LABOURMore than 50%of the surveyed children in Lebanon arecurrently working or have worked in the past.Children experiencingPHYSICAL or SEVERE VERBALVIOLENCE AT SCHOOLLIVING CONDITIONS67%Southern SyriaOVERCROWDED HOMESJordan 18%three or more persons living in one roomLebanon45%73% 80% 73%35inSouthern Syriasurveyed children in Lebanon areJordanLebanonNOT ATTENDING SCHOOL.UNSAFE HOUSINGIn Southern SyriaIn Lebanon57%27%inadequate access to water, electricity,hazard and structural damage66%of the surveyed children are in33%NEED FOR EXTRA HELPSouthern Syria Jordan Lebanonor remedial assistance for school work.Southern en receiveNO PSYCHOSOCIAL SUPPORT20%Southern Syria12%Jordan20%Lebanonin school.HEALTHNO ACCESS TOHEALTH CARE59% 58% 54%Southern JordanSyriaLebanonThe survey is not illustrative of country-wide statistics and does not represent populations outside of the survey areas.-7-

TOLERATING STRESSORSTheir testimonies provide a snapshot of dailystressors that they tolerate and accept in themidst of conflict and displacement.had experienced domestic violence. In Lebanon,39 per cent and in Jordan 15 per cent of childrensurveyed talked of violent discipline in the home.In Lebanon, 63 percent of childrenEDUCATIONWorld Vision spoketo said they were notattending school. In Jordan and in Syria numberswere much lower, with only six per cent ofchildren in Jordan saying they were not in schooland seven per cent of children in Syria.HEALTHCAREAccording to the answers in the survey, life inSyria is unsurprisingly much more precarious andharmful conditions are more prevalent than inLebanon and Jordan. However, the survey resultsalso show that refugee children in Lebanonstruggle more than those in Jordan.In Syria, 57 per centof children who wentLEARNINGto school say theystruggle to learn.They expressed frustrations with the curriculumand the classroom environment. In Lebanon thefigure was also significant at 27 per cent. InJordan, only five per cent of children who went toschool believed they were struggling to learn.In Syria, 42 per centsaid they havewitnessed violentdiscipline by teachersand other school staff compared to 17 per cent inLebanon and 10 per cent in Jordan.CORPORALPUNISHMENTIn Lebanon, 55 percent of children saidthey had worked orwere working ascompared to 11 per cent in Jordan and eight percent in Syria.CHILDLABOUROVERCROWDEDHOUSINGOver 70 per cent ofall children surveyedlive in overcrowdedhousing.12In Lebanon, 63 percent, Syria, 66 percent and Jordan, 33per cent live inunsafe housing.Unsafe housing can include environmentalhazards, structural damage, no electricity, or noaccess to water.UNSAFEHOUSINGDOMESTICVIOLENCEMore than half of allchildren surveyedsaid they do not haveaccess to health care.In Syria, 50 per centof children said they-8-

According to the survey, there are higher levelsof corporal punishment in Syria than in Jordanand Lebanon. Teachers?own stressors andhardships may have a spill over effect in theclassroom. Therefore, efforts to providepsychosocial support to children should alsoextend to teachers to ensure appropriate copingmechanisms for everyone in classroom settings.Children in each country highlight differentstressors, which means that programmes toaddress their needs must be context specific,culturally appropriate and specific to eachenvironments.The findings also show that children continue toface violence as a stressor at home, at schooland in communities.The survey found little access to psychosocialservices in school settings, with 89 per cent ofchildren in Syria, 83 per cent in Jordan and 71 percent in Lebanon never having received theseservices. School must be a place of protection andsupport that builds resilience and the opportunityto learn.The data showed that children living inovercrowded housing were twice as likely toexperience violence in their homes. These samechildren express more nervousness about theirschoolwork and claim more barriers to learningthan children living in less populated housingconditions.In Lebanon, 57 per cent of children surveyedwork in the labour market.These children belongto families where the head of household is notemployed. The majority of these children confirmthat they supplement the household income tomaintain basic needs.Studies also confirm these same negative effectsfrom overcrowded housing on children?swell-being because children need space andprivacy to do homework, develop identity,maintain protection, practice skills and sleep.13Overcrowded housing is prevalent in all threecountries.The survey suggests that economic pressures, likein many settings, act as one push factor forchildren seeking employment. The survey showedthat 75 per cent of children working are notattending school.-9-

RECOMMENDATIONSIn all three countries, World Vision?s illustrativesurvey found children yearn for family reunions atthe earliest opportunity and hope for peace.Almost all children aspire to attendpost-secondary education. Despite all they havefaced, and continue to face every day, Syria?schildren are a source of hope for the country?sfuture.of extreme vulnerability where children andfamilies are unable to access basic services,both in Syria and in refugee settings, must beprioritised, not ignored.- At the local level, host governments anddonors must encourage strongeraccountability mechanisms both in host andrefugee communities to empower the affectedchildren and communities to participate inprogramme decision-making and servicemonitoring.14 This can strengthen access toservices and systems, create efficiencies indelivery and identify responsibilities on bothsides that need to be emphasised to bettersupport children, their families andcommunities.15In part, their futures will be defined by actionsthat take Syria?s children beyond survival. To dothis, the magnitude of harmful conditions enduredby Syrian girls and boys must be reduced,education must be provided, resilience building todecrease the effects of daily stressors needs to beoffered and local level child protectionmechanisms need to be scaled up to preventviolence as a key stressor in the lives of children.To decrease t he effect s of daily st ressor s;To reduce t he m agnit ude of har m fulcondit ions endured by Syr ia?s gir ls andboys;- Donors must prioritise funding for mentalhealth and psychosocial support programmes(MHPSS). These programmes promoteresilience and positive coping mechanisms andhave shown to reduce levels of stress,insecurity, emotional and behaviour difficultyand protect childhood developmenttrajectories.16 Mental health and psychosocialsupport programmes strengthen socialsupport networks that enhance trust and- At the national and local levels, hostgovernments and donors must concentratesupport efforts for children who experiencemultiple and overlapping stressors. Thesechildren are at higher risk of long-termnegative health and social outcomes. Pockets- 10 -

tolerance among youth, help to developreconciliation, enable children to becomeactive agents in their communities and restorespaces for children to develop the skills andbehaviours appropriate to their age groups.- Donors must renew efforts to fully fund theeducation of Syrian girls and boys. At the timeof writing, current donor funding foreducation was 50 per cent less than it was atthis time last year. With such losses, hostcountries cannot continue to maintain thesame numbers of refugee children in schoolor the quality of education. To expand access,donors must increase funding for mobileschools, push for informal education that isrecognised and accredited and digitisecurriculums.that include reporting and referralmechanisms, with case managementmethodologies and specific services thatrespond to children in need of protection.Social workers should be integrated intoschools and community services, includinghealth centres, to offer multi-sectoral supportto prevent violence and protect children whoare exposed to it.- Donors must support funding and innovationsin the education, child protection, and healthsectors to shift attitudes and create newbehaviours in caregivers and others whodirectly influence the day-to-day lives ofchildren. These interventions must also equipparents, caregivers and teachers with the skillsand coping mechanisms to prevent violence.- Donors must increase funding to end violenceagainst girls and boys. A 2017 review of officialdevelopment assistance (ODA) ? the reportCounting Pennies17 - found that in 2015, lessthan 0.6 per cent of total ODA spending wasallocated to ending violence against children.Violence severely impacts children?sdevelopment, health and education and has ahigh cost for society ? up to US 7 trillion ayear, worldwide. Syria?s families and childrenneed assistance to ensure survival, protectionand to avoid serious and long-term healthconditions.To prevent violence against gir ls and boys;- The UN Security Council and countries withinfluence must take steps to secure the fullsupport of all parties to the conflict to ceasehostilities and return to the negotiating table.The war must stop. Parties to the conflictmust be held fully accountable for the scale ofviolence that children inside Syria have beenrepeatedly exposed to and the resultantviolations against children, which have robbedchildren of their right to physical andpsychological well-being.- National and local actors must strengthenformal and informal child protection systems- 11 -

WORLD VISION RESPONDSTO CHILDREN LIVING WITHSTRESSORSChild friendly spaces in Idleb, Syria, offer life-skillscourses to build constructive relationships withpeers and adults as well advising on health,hygiene and positive social behaviour.The Back to Learning campaign targeted hard toreach areas in Southern Syria and engaged over2,000 people, resulting in high registration ofchildren in World Vision?s catch-up classes.from violence was the World Vision priority andincluded:- working with schools, parents?groups andfaith leaders to encourage families, andneighbours, to provide the safest possibleenvironment engaging teachers to promoteprotection and inclusion in schools;- training parents and caregivers in positive,nonviolent ways to discipline children;- establishing community-based child protectioncommittees to recognise and refer cases ofviolence or other rights violations againstwomen and children.In Syria, over 5,000 people per month receivedmessages about child protection issues throughmobile teams in schools and child friendly spaces,camps and communities, particularly around thenegative physical and psychological effects of childlabour as school has been interrupted and familiesare in desperate need of money.Child friendly spaces in Lebanon includingpsychosocial support activities resulted in 57 percent of children feeling better and more secure.In 2017, using local strategies to protect children1. 2017 Humanitarian Needs Overview, Syrian Arab Republic, p. 6, found public-enar2. 2018 Humanitarian Needs Overview, Syrian Arab Republic, found public-enar3. Research was conducted in Southern Syria (Dara?a and Qunaitra) and in refugee camps and host communities in Lebanon (Central Bekaa, West Bekaa,Akkar) and Jordan (Amman, Mafraq, Zarqaa and Irbid) during February 2018. The survey is a purposive sample that is a non-representative subset of the largerpopulation of refugees in Jordan and Lebanon and displaced persons inside Syria. The sample is constructed to show that children are experiencing multiplestressors in the settings where they live. The findings are based on desk review of existing reports and field research in urban, rural, and camp settings.Information was gathered through interviews with children living inside Syria and refugee children from Syria (boys and girls) and adolescent in the age rangebetween 11 and 17. The survey respondents were participants in World Vision programming that offers psychosocial support. All interviews were conductedthrough one to one interview using both open-ended and close-ended questions. The interviewers were trained to identify the answers of open-ended andclose-ended questions from their discussion with children. This methodology was employed to avoid bringing children?s attention to their daily hardships. Inaddition, this methodology allowed the interviewer to monitor the well-being of the child as the interview proceeds and take corrective steps accordingly.4. IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings,http://www.who.int/mental health/emergencies/guidelines iasc mental health psychosocial june 2007.pdfMiller, K. E. & Rasmussen, A., "War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide betweentrauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks,? 23 October 2009, Social Science & Medicine 70 (2010) 7?16.5. Self-Brown, S., LeBlanc, M., & Kelley, M. L. (2004). Effects of violence exposure and daily stressors on psychological outcomes in urban adolescents. Journal ofTraumatic Stress, 17(6), 519?527.6. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey ACE Data, 2009-2014 (2015). Atlanta, Georgia.7. Ibid, at 4.8. A study of Panter-Brick et al. (2017) with Syrian Refugees control groups in Jordan, on their eight weeks programme of psychosocial structured activitiesshowed that PSS has not only beneficial impact on symptoms of stress, insecurity, emotional and behavioural difficulty, but also protects developmenttrajectories of youth facing conflict and displacement.9. UN OCHA figures, March 2018, http://www.unocha.org/syrian-arab-republic; UNICEF Syria Crisis update, January n%20Situation%20Report%2C%20January%202018.pdf10. The survey methodology relied upon both open-ended and close-ended questions to provide space to hear from children and also to validate theirresponses and feelings.11. Betancourt, TS. & Williams, T., (2008). Building an evidence base on mental health interventions for children affected by armed conflict. InternationalJournal of Mental Health, Psychosocial Work and Counseling in Areas of Armed Conflict, 6(1):39?56.12. This is based on WHO definition of overcrowded housing as 2.5 or more persons living in the same ding.pdf13. Solari, C. & Mare R. (2012). Housing Crowding Effects on Children?s wellbeing. Social Science Research, 41(2); 464-467.14. UNICEF (2012), The Role of Child and Youth Participation in Development Effectiveness, A Literature /files/Role of Child and Youth Participation in Development Effectiveness.pdf15. Panter-Brick, C., Dajani R., Eggerman M., Hermosilla S., Sancilio A. & Ager A. (2017). Insecurity, distress and mental health: experimental and randomizedcontrolled trials of a psychosocial intervention for youth affected by the Syrian crisis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry.16. n/evaluation-child-friendly-spaces17. -against-children- 12 -

World Vision InternationalExecutive OfficeRoundwood AvenueStockley Park Uxbridge,Middlesex UB11 1FG, UKWorld Vision JordanPrincess Sumayya Bent Al Hasan Street,7th Circle next to Safeway, Al HuseiniBuilding # 22 - Sweifieh, P.O. Box941379, Amman 1149

of negative coping mechanisms for survival escalates. In February 2018, World Vision spoke to 1,254 Syrian girls and boys in Southern Syria, Jordan and Lebanon.3 They talked about their daily lives, their hopes for the future and the things they think about. Their stories included war-induced violence, displacement, and missing, separated

![[ST] Survival Analysis - Stata](/img/33/st.jpg)