Transcription

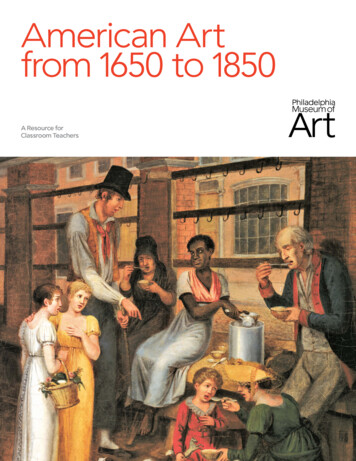

American Artfrom 1650 to 1850A Resource forClassroom Teachers

American Art from 1650 to 1850A Resource forClassroom Teachers02 Introduction03 Acknowledgments04 Maps07 Peale Family Tree08 Connections to Educational Standards10 Global Connections12 Punch Bowl Showing the Factories of Canton, China14 Pepper-Pot: A Scene in the Philadelphia Market16 The Peaceable Kingdom18 From Indian and Mestiza, CoyoteFrom Spaniard and Morisca, Albino20 San Diego de Alcalá (Saint Didacus of Alcalá)22 Power and Portraiture24 Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Mifflin (Sarah Morris)26 Portrait of Yarrow Mamout (Mamadou Yarrow)28 Benjamin Franklin Drawing Electricity from the Sky30 Portrait of Sor (Sister) Juana Inés de la Cruz32 Peale’s Museum34 Staircase Group (Portrait of Raphaelle Peale and Titian Ramsay Peale I)36 Cut-Paper Profiles38 Grapes and Peaches40 Crafting Identity42 Dish (Pennsylvania German)44 Dinner Platter (Wild Turkey)46 Wardrobe (Kleiderschrank)48“The Fox and the Grapes” High Chest of Drawers0222-14109CONTENTS1

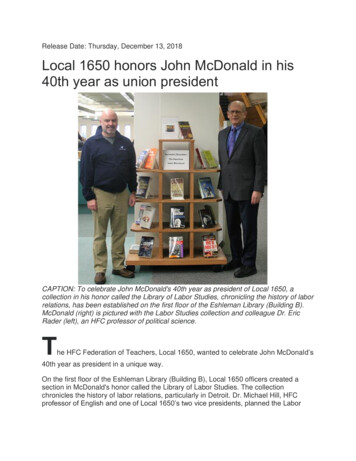

IntroductionAcknowledgmentsThe Philadelphia Museum of Art is home to an exceptional collection of Americanart. The work that spans the years 1650–1850 reflects the global forces that shapedthe new United States and Philadelphia’s central role as its cultural capital.American Art from 1650 to 1850: A Resource for Classroom Teachers wasdeveloped by the Division of Education at the Philadelphia Museum of Art andwritten by Rebecca Mitchell and Suzannah Niepold. It was edited by Amy Hewittand designed by Barbara Barnett. We are grateful to our museum colleagueswho contributed their expertise, insight, and support to the creation of thisteaching resource, especially Barbara Bassett, Kathleen A. Foster, Rosalie Hooper,Alexandra Kirtley, Sarah Shaw, and Carol Soltis. We received invaluable supportfrom additional experts, including Jean Woodley and Dr. Mey-Yen Moriuchi. Finally,we thank the Philadelphia area educators who provided us with essential guidanceand feedback: Audra dePrisco, Erin Haley, Roberta Jacoby, Joy Lai, Julie McNulty,Christine Meiskey, Andrea Mogck, Valerie Oswald-Love, and Tamarah Rash.This teaching resource highlights works of art chosen by educators to reflectmultiple perspectives on the history of the United States. The selection spotlightslesser-known or overlooked stories of the experiences of Black, Latinx, Asian,and Indigenous people as well as women. These works are sorted into fourthemes that highlight relationships among them: Global Connections, Power andPortraiture, Peale’s Museum, and Crafting Identity.We hope that you and your students enjoy exploring these works of art andmaking meaningful connections, both among them and to other things you learn.We also invite you and your students to the museum to see firsthand the artworksfeatured in this resource along with many more.How to Use This ResourceThis booklet provides an introduction, background information about selectedartworks, and suggested curriculum connections to classroom teachers. Thedigital presentation included on the enclosed USB card is designed as a teachingtool. The presentation includes additional images and text that will help youengage your students in looking closely at and responding to the selectedartworks. The USB card also contains a collection of multimedia files to engageyour students in American art and history. Many videos are also available atyoutube.com/c/philadelphiamuseumofart. The booklet and presentation arealso available for download at philamuseum.org/teacherresources.SupportThe installation of the new Early American Art galleries has been made possiblewith lead support from the Henry Luce Foundation, and by The Mr. andMrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation for the Arts, The Richard C. von HessFoundation, National Endowment for the Humanities: Democracy DemandsWisdom, an anonymous donor, The Davenport Family Foundation, Edward andGwen Asplundh, Dr. and Mrs. Robert E. Booth, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. James L. Alexandre,The Americana Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. S. Matthews V. Hamilton, Jr., The McLeanContributionship, Lyn M. and George M. Ross, Dr. Salvatore M. Valenti, the WunschFamily, Donald and Gay Kimelman, Boo and Morris Stroud, Mr. and Mrs. Ronald C.Anderson, Matz Family Charitable Fund, Marsha and Richard Rothman, and othergenerous donors.Additional support for the museum’s building project, including the constructionof the new Early American Art galleries, was provided by Robert L. McNeil,Jr., Leslie Miller and Richard Worley, Laura and William C. Buck, Kathy and TedFernberger, Joan and Victor Johnson, John and Christel Nyheim, Lyn M. andGeorge M. Ross, National Endowment for the Humanities, Marsha and RichardRothman, and other generous donors.Ongoing support for American Art initiatives and programs is provided by theCenter for American Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, established by RobertL. McNeil, Jr.2INTRODUCTIONACKNOWLEDGMENTS3

The United States’ GlobalConnections around 1800KEYThis global map will help students place the works of art in this resource intothe larger political, economic, and geographical context of the time period.U nited States Trade with ChinaC R aw Materials including LumberManila Galleon Trade Route (inset)D Sugar, Molasses, FruitT ransatlantic TradeE Rum, Iron, Gunpowder, TobaccoA E nslaved Persons, Gold, SpicesF Enslaved Persons, Sugar, MahoganyBG Fish, Flour, Livestock Manufactured Goods, Textiles, Furniture, LuxuriesGREATBRITAINNew YorkLOUISIANATERRITORY zhou(Canton)GGUINEAAcapulcoManilaPHILIPPINESEWEST AFRICANSLAVE TRADE REGIONSManila Galleon Trade RouteJAPANGuangzhou(Canton)MAPSUNITEDSTATESPacific OceanNew YorkPhiladelphiaNEWSPAINManilaPHILIPPINES4CHINAw SpainATrade route to Asia (see inset)CHINAo Neroute tTrade set)n(see iDAcapulcoMAPS5

Map of Pennsylvania around 1800Peale Family TreeBefore British colonization, these lands were the traditional territories of the Delaware, Susquehannock, Shawnee, andIroquois People. By 1800, many of these indigenous communities had been displaced by British and German immigrants.This partial family tree shows the artistic dynasty that descended from three siblings: Charles, Elizabeth, and James Peale.Ten of their eighteen children (see bold *) became artists. We have included pictures of Peale family members referencedin this resource (see bold). Some of the portrayals are self-portraits while most others are likenesses created by familymembers.MarriedRachel Brewer1744 – 1790CharlesWillson Peale*1741 – 1827see pages 26 – 27and 33 – 39Montgomery CountyRaphaelle Peale*1774 – 1825Germantownsee pages 34 – 35 and 39PhiladelphiaPredominantEthnic GroupAngelica Kauffmann Peale1775 – 1853GermanLancasterBritishElizabeth PealePolk*1747 – around 1776Map of Philadelphiaaround 1800Charles PealePolk*1767 – 1822Maria Peale1787 – 1866Elizabeth BordleyPolk1770 – ?James Peale Jr.*1789 – 1876Anna ClaypoolePeale*1791 – 1878COLUMBUS BLVDFRONT STREET2ND STREET3RD STREET4TH STREET5TH STREET6TH STREETSarah MiriamPeale*1800 – 1885Rubens Peale*1784 – 1865Penn Treaty Parksee pages 36 and 39(Shackamaxon)Two Miles NorthMary Jane Peale*1827 – 1902MarriedHigh Street Marketssee pages 38 – 39Eliza BurdPatterson1795 – 1864HIGH STREET (now known as Market Street)Sophonisba Peale*1786 – 1859Benjamin Franklin HouseState House(now known as Independence Hall)DELAWARE RIVERMifflin HouseCHESTNUT STREETMargarettaPeale*1795 – 1882see pages 34 – 35ARCH STREETJames Peale*1749 – 1831Jane RamsayPeale1785 – 1834Titian Ramsay Peale I1780 – 1798Moses Williams HouseMarriedMary C.Claypoole1753 – 1829Margaret JanePolk1766 – ?Rembrandt Peale*1778 – 1860RACE STREET7TH STREETMarriedRobert Polk1744 – 1777MarriedElizabethDePeyster1765 – 1804see page 36Titian Ramsay Peale II*1799 – 1885Image credits: one of the works on this chart is partof the George W. Elkins Collection. Three works ofart are gifts of the McNeil Americana Collection. Thephotograph of Mary Jane Peale is courtesy the AmericanPhilosophical Society.Philosophical HallWALNUT STREET(Home of Peale's Museum, 1794 – 1802.Then expanded to the State House.)PEALE FAMILY TREE7

Connections toEducational StandardsCommon Core State StandardsNational Visual Arts StandardsEnglish Language Arts/Literacy Standards College and Career ReadinessAnchor Standard for ReadingResponding: Understanding and evaluating how the arts convey meaningStandard 7: Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media andformats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.Anchor Standard: Interpret intent and meaning in artistic work.College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for WritingStandard 9: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis,reflection, and research.College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Speaking and ListeningStandard 1: Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations andcollaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing theirown clearly and persuasively.Anchor Standard: Apply criteria to evaluate artistic work.Connecting: Relating artistic ideas and work with personal meaning andexternal contextAnchor Standard: Relate artistic ideas and works with societal, cultural, andhistorical context to deepen understanding.Anchor Standard: Synthesize and relate knowledge and personal experiencesto make art.Standard 2: Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media andformats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.National Council for the Social StudiesStandard 4: Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such thatlisteners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization, development,and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.C3 Framework for Social Studies State StandardsEnglish Language Arts Standards History/Social StudiesStandard D2.Geo.7: Explain why and how people, goods, and ideas move fromplace to place.Standard 1: Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary andsecondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to anunderstanding of the text as a whole.8Anchor Standard: Perceive and analyze artistic work.Standard D2.Geo.2: Use maps, graphs, photographs, and other representations todescribe places and the relationships and interactions that shape them.Standard D2.Geo.11: Explain how the consumption of products connects peopleto distant places.Standard 2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondarysource; provide an accurate summary that makes clear the relationships amongthe key details and ideas.Standard D2.His.2: Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.Standard 7: Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented indiverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in orderto address a question or solve a problem.Standard D2.His.10: Compare information provided by different historical sourcesabout the past.CONNECTIONS TO EDUCATIONAL STANDARDSStandard D2.His.4: Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced theperspectives of people during different historical eras.CONNECTIONS TO EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS9

GlobalConnectionsThe art of the Americasreflects a complex historyof colonization, slavery,immigration, and trade.These forces brought togetherthe knowledge and customsof Indigenous people,Europeans, Africans, andAsians. In this context, artistsdeveloped new Americancultural traditions, using theirvoices to promote and shapethe ideas of their time.Many of the artworks thatsurvive were created forwealthy patrons and presenthistory from the point of viewof those in power. Investigatingthe layered stories of eachobject can reveal thecontributions of Indigenousnations, immigrants, traders,and people brought here inbondage. These important, yetoften untold stories prompt usto think about the multifacetednature of American culture,shaped by global connections.10CurriculumConnectionsAdaptable for all grades/ArtResearch the origins of a fruit, vegetable,spice, or recipe that we eat in America.Create a collage or still life that tells itsstory. Is it indigenous to the Americas?How has it been cultivated, prepared,and consumed over time? Reflect as aclass on the global culinary reach of foodinfluences in the United States.Adaptable for all grades/Criticalthinking skillsFocus on a single work of art. Recordyour first impressions. Read thebackground information and discusswith a partner. How did your perceptiongrow or change? How does this artworkconnect to your understanding ofUnited States history? How do imagesaffect our understanding of history?Middle and High School/SocialStudiesPhiladelphia was a center for Free Blackartisans and entrepreneurs, includingThomas Gross, James Forten, RobertBogle, and Peter Bentzon. Researchone of these makers and create apresentation to share with your class.Discuss: What does that person’s lifestory tell us about the experienceof the Free Black community inPhiladelphia when slavery still existedin the United States?High School/Social StudiesThere is no scientific basis for race, butEnlightenment thinkers developedbiological justifications for the socialconstruct. Research the origins of thisso-called scientific racism. Considerhow images and texts reinforcedpower structures. How do theseinvented concepts continue to affectsociety today? How can we continue todebunk these harmful misconceptions?GLOBAL CONNECTIONS 11

Punch BowlShowing Factoriesof Canton, ChinaLayers of architecture and activity are packed into thedecoration of this punch bowl. The scene is set in theChinese port of Guangzhou (gwaang-JOW, also known asCanton). In the foreground, small river boats cluster at thegates. They transport goods such as tea, silk, and porcelainfrom large ships to merchant buildings. Each building isa hong, or center of trade between China and anothercountry. Merchants from different countries used their hong,also called a factory, as an office, warehouse, and hotel.The flags flying in front of each factory represent thenation that traded there. The American and British flagshang beside each other, a powerful symbol given that theRevolutionary War had just ended in 1783. After protestingunfair taxation on Chinese goods, such as the tea thrownoverboard in Boston in 1773, the new nation won the abilityto trade directly. The first United States merchant ship sailedfor China just one month after the war ended. Establishingtrading relationships was important both for the newcountry’s economy and the recognition of its independence.To protect their own nation, the Chinese government strictlycontrolled access to the country. The port of Guangzhouwas the only area open to European and American trade.The blend of these influences is clear in the design of thehongs and the people’s clothing. Classical Roman columnsand pediments stand beside window screens with Chinesepatterns. European merchants are dressed in tricorn hats andknee-length frock coats while their Chinese counterpartswear long robes and rounded hats.Chinese artisans developed the methods to make porcelainand kept this knowledge a closely guarded secret for almostfive hundred years. Prized for their brilliant white surfaces,colorful decoration, and durability, porcelain objects werehighly desirable and expensive, especially since they wereshipped halfway around the world. Punch bowls, a partycenterpiece used to serve a mixed drink, were made for exportto the United States where they would have demonstrateda host’s status and connections to the wider world.Around 1790 Made in China for export to the American marketPorcelain with overglaze enamel decorationDiameter: 14 3/8 in (36.5 cm)On loan from The Dietrich American Foundation12Bowl, late1700s or early1800s, madein Japan (Gift ofMr. and Mrs. RalphBalestrieri, 1963-47-2)Compare and ConnectThis bowl was made in Japan for aJapanese audience. Protective traderestrictions meant that many Japanesepeople had never seen a Europeantrader. How does this object compareto the punch bowl made in China for anAmerican market?Find more detailed images and lookingprompts in the digital presentation.Let’s LookWhat kind of object is this? Does itremind you of something you use?How would you describe thesebuildings? How are they similarand different?How does the shape of the objectimpact the design of the image?Imagine stepping into this scene.What could you hear, smell, or touch?How many flags can you identify?What do the flags tell you about thepeople in the artwork?GLOBAL CONNECTIONS 13

Pepper-Pot:A Scene in thePhiladelphia MarketOutdoor markets were one of the rare places in Philadelphiaduring the early 1800s where people of all ages, professions,social classes, and races would interact. For an artist, theyprovided a lens to study these exchanges. In this painting,the circle of people around the soup vendor includes a tallman from the country, an older woman, a former soldier, akneeling woman feeding a young boy, and two girls witha basket of flowers. There are some elements of harmonybetween them, like in the shared gesture of raising a spoonor tilting their heads. But there are also signs of discomfort:the two girls, dressed in the fancy clothes of wealthycity families, look at the old soldier, perhaps with pity orcondescension. Their bright footwear stands out in contrastwith the bare feet of the street vendor, alone in the centerof the group.John Lewis Krimmel was born in Germany and had onlyarrived in Philadelphia a year before painting Pepper-Pot.His observation of street life in his adopted city appealedto his contemporary museum audiences. He providedan immigrant’s perspective on society in a country justbeginning to establish its national identity.One aspect of life in the United States that was differentfrom Germany was the presence of the large Free Blackcommunity. Many of the jobs that were open to Blackpeople depended on white attitudes about what wasappropriate. For entrepreneurial Black women withoutprofessional training, cooking and selling food was analternative to domestic labor. Black female street vendorswere an important part of Philadelphia’s economy by 1811.Many of them achieved economic self-sufficiency despitediscrimination. Pepper-pot soup was a popular dish oftensold by Black women on High Street (see map on page 6).Over many generations, as people were forcibly transportedto Philadelphia through the transatlantic slave trade,they incorporated food traditions of West Africa and theCaribbean into the spicy soup still enjoyed today (see mapon page 4).1811 John Lewis Krimmel (American, born Germany, 1786–1821)Oil on canvas19 1/2 x 15 1/2 in (49.5 x 39.4 cm)125th Anniversary Acquisition. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edward B. Leisenring, Jr., 2001-196-114Double Chest, 1805–10, by Thomas Gross, Jr.(Gift of Mrs. Leslie Legum, 1983-167-1a,b)History ConnectionIn the 1800s, Philadelphia’s Free Blackcommunity included many talentedartisans. However, it was rare for anyfurniture maker to sign their pieces,so it’s difficult to identify their worktoday. When cabinetmaker ThomasGross wrote his name on the undersideof this chest, he made an importantcontribution to Black history.Find more detailed images and lookingprompts in the digital presentation.Let’s LookWhat is going on in this picture?How would you describe the peoplein this scene? What clues can you findto each of their identities? What makesthem similar or different?How are the people interacting? Whatkinds of conversations can you imaginethem having with each other?Why might the artist have chosen topaint this scene? What does it revealabout life in Philadelphia in 1811? Whatquestions does it raise?GLOBAL CONNECTIONS 15

The PeaceableKingdomGentle animals gather around a barefoot young child inthis wooded landscape. Behind them, a large ship floats ina tranquil river. On the grassy riverbank, a group of peoplemeet under an elm tree. Look closely at their clothing andyou’ll notice that the men on the right are British colonistswhile the men on the left are Indigenous Americans. Whatcould they be discussing?Both scenes are meant to tell stories of peace. The child andanimals in the foreground illustrate a passage from the Bible.In this story, the prophet Isaiah predicts that one day all ofthe world’s creatures will live peacefully together:The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and theleopard shall lie down with the kid . . . and a little childshall lead them. And the cow and the bear shall feed;their young ones shall lie down together: and the lionshall eat straw like the ox. . . . They shall not hurt nordestroy in all my holy mountain. (Isaiah 11:6–9, KingJames Version)In the painting, Edward Hicks connected Isaiah’s vision to thelegendary meeting between William Penn and the Lenape(Luh-NAH-pay, also known as the Delaware) chief Tamanendthat took place at Shackamaxon, near Philadelphia, in 1682(see map on page 6). The story holds that Penn proclaimed:Armband, 1792–95, shop of Joseph Richardson Jr.(On permanent deposit from The Dietrich AmericanFoundation Collection to the Philadelphia Museum of Art)History ConnectionThis silver armband is engraved withthe Great Seal of the United States.The exchange of diplomatic gifts wasan important part of negotiationsbetween the federal governmentand Indigenous nations. Whateverthe intentions of these gifts, by thetime this armband was made, whiteAmericans had destroyed or displacednearly all of the Native Americansettlements in Pennsylvania.Find more detailed images and lookingprompts in the digital presentation.We meet on the broad pathway of good faith andgood-will; no advantage shall be taken on either side,but all shall be openness and love.Hicks, a Quaker like Penn, painted this picture almost 150years after the event occurred. His message of peace wasintended as an example for his Quaker neighbors, who werein the midst of disagreements. Today, we understand thatthe terms of the original treaty had not been honored andmost of the Lenape had been displaced to the Midwest bythe time Hicks painted this image. Nevertheless, the peaceagreement between Penn and the Lenape remained asymbol of harmony for the artist.Let’s LookWhat is going on in this picture?If you could step into this landscape,how would it feel?What kind of relationship do theanimals and child share? How canyou tell?1826 Edward Hicks (American, 1780–1849)Oil on canvas32 7/8 x 41 3.4 in (83.5 x 106 cm)Bequest of Charles C. Willis, 1956-59-116How did Hicks draw our attentionfrom one scene to the next? Whatseparates the two scenes?GLOBAL CONNECTIONS 17

Top:From Indian and Mestiza, CoyoteBottom:From Spaniard and Morisca, AlbinoThese artworks, known as casta paintings, illustrate a systemof racial hierarchy invented by elites in Spanish America toplace themselves at the top of a caste system (see map onpage 4). Each scene contains two parents of different racesand their child. The labels at the top use terms* that definethe racial heritage of each person. At the top of this castesystem are families with the greatest percentage of Europeanancestry, followed by racial mixes between Indigenous peopleand then Black Africans. These two images are probably partof a set of sixteen canvases, illustrating a system of strictstratification that was much more fluid in reality.In the bottom image, we are presented with a Spanish father,a Morisca mother (Spanish and African ancestry), and theirchild. The father and son wear elegant European clothing,conveying their higher status. The family uses expensive glassand ceramic objects, and a horse is visible in the background,another symbol of wealth. In the top image, the artistdepicts an Indigenous father, a Mestiza mother (Spanishand Indigenous ancestry), and their child. The father’s lowersocial status is shown in the simple draped cloth he wears. Thetable is overflowing with root vegetables in woven basketsand platters, perhaps items the father will sell at the market.Notably, both mothers in the paintings look similar, withrebozos (shawls) and beauty marks, suggesting that thesefigures were based not on individuals but types, and that thesame model may have been used throughout the series.When the Spanish first colonized Spanish America, marriagesbetween different races were common as initially few womenimmigrated to New Spain and marriages could be used toform alliances. As the false idea that there was a scientificbasis for race emerged, the Spanish government developedthe Casta System, which included a series of privileges andrestrictions, to maintain their power and superiority over otherracial groups. The legal system was abolished when Mexicowon its independence from Spain in 1821 but continues to havelasting impact on racial identities and social structures.Around 1760 Attributed to José de Alcíbar (Mexican, 1725/30–1803)Oil on canvas31 x 39 3/4 in (78.7 x 101 cm)Gift of the nieces and nephews of Wright S. Ludington in his honor, 1980-139-1,218* These terms were created as part of the development ofthe caste system and should not be used in reference torace or ethnicity.Let’s LookCompare and contrast the two images.What similarities or differences canyou find?How is each family interacting?What do you notice about the wayspeople are dressed?What details can you find in eachscene? What do they tell you aboutthe people’s daily lives?What do you think the artist isconveying about the social status ofeach family? What do you see thatmakes you say that? What does thatreveal about the culture of New Spain?GLOBAL CONNECTIONS 19

San Diego de Alcalá(Saint Didacus ofAlcalá)This small religious painting connects the arts and culture ofthree continents.Born in Spain, San Diego de Alcalá is a Catholic saint honoredfor his devotion to the poor and sick. In this image, he standsin the garden of a monastery wearing a simple tunic. Hisbare feet symbolize his humility. With one hand he supportsa large cross, a reminder of sacrifice. In the other, he holds abasket of bread and flowers. These symbols are a referenceto one of the miracles he performed, where bread he hadstolen to feed the hungry was transformed into roses toconceal the theft. The garden is echoed in the frame, wherean abundance of grape vines filled with birds connect thepainting to the wine used in religious rituals.The shimmer visible in San Diego’s robes and many otherparts of the painting is created by the addition of motherof-pearl, which is the iridescent inner layer of a mollusk shell.Artists create these enconchado paintings by insertingpieces of shell into the panel like tiles in a mosaic. In a timewhen art was lit by candles, the flicker of light across the shellwould create movement and luminosity. Small paintings likethis one were objects of personal devotion, and the richnessof the materials was intended to inspire reverence.Indigenous people in the Americas made shellwork paintinglong before Spanish colonization. Enconchados of religiousimagery gained popularity during the colonial period asspreading the Catholic faith was one of the main goals ofthe Spanish as they gained control in New Spain (see mapon page 4). Religious art like this painting was used as amissionary tool in that effort. This work was likely paintedby a Criollo artist, someone of Spanish descent born inthe Americas.The Spanish also used their colonies as a base for trade withAsia. New trade routes led to an exchange of artistic ideasand materials. Enconchado paintings were inspired by jewellike Japanese lacquerware with inlaid shell and Indigenousshellwork traditions. This melding of cultures expressed aunique identity, distinct from their European ancestors.Late 1600s Made in MexicoOil and mother-of-pearl inlay, with tempera accents, on panel18 1/4 x 15 3/4 in (46.4 x 38.7 cm)Purchased with the Edith H. Bell Fund, 2015-166-120Let’s LookHow would you describe the personin this painting? What is he wearing?What is he holding?What can you tell about the setting?What animals and plants can you find?What colors stand out to you? Canyou find them in both the picture andthe frame?What do you notice about texture?Which areas seem shiny?GLOBAL CONNECTIONS 21

Power andPortraiture22What can portraits tell us?At first glance, they candescribe a person’s physicalappearance. Looking moreclosely, they can communicatewhat was important to thesitter. They can suggestinformation about theirpersonality, beliefs, andaspirations. Many portraitsare commissioned, meaningthat the sitter paid the artistto create it. Other times,artists choose a person tohonor, sometimes long aftertheir death. In the 1700s andearly 1800s, commissioning aportrait was expensive, andso most paintings from thatperiod depict individuals fromwealthy and powerful groupswho lack racial, religious, andsocioeconomic diversity.However, as this selection ofportraits demonstrates, theAmericas were home topeople with many different lifeexperiences and backgrounds.CurriculumConnectionsAdaptable for all grades/ArtCreate a portrait of yourself orsomeone you want to honor. Considerpose, facial expression, setting,clothing, and other objects to expressimportant aspects of their identity.Were you inspired by any of theartworks in this guide?Adaptable for all grades/LanguageArtsSelect a portrait and write a letter tothe sitter. What do you see in theirportrait that makes you curious? Letthem know what you wonder abouttheir life, what you admire about them,and what you wish you could tell them.Middle and High School/ScienceResearch Benjamin Franklin’s kiteexperiment. Why did Franklin conductit? How did he use the results to solvea problem? Identify a problem in yourdaily life and brainstorm solutions.What experiments would help withyour design?High School/Social StudiesCompare and contrast the portraits inthis guide. What do the objects, poses,clo

The Philadelphia Museum of Art is home to an exceptional collection of American art. The work that spans the years 1650-1850 reflects the global forces that shaped the new United States and Philadelphia's central role as its cultural capital. This teaching resource highlights works of art chosen by educators to reflect