Transcription

Eademote cameras capture images of elusivesnow leopards; high-speed electronic flashfreezes every feather of a hummingbirdin midaiq creative blur reveals sprintingzqodqizqcheetahs as wdve never seen them before.We are so used to seeing amazing wildlifephotographs that it's hard to imagine what it must havebeen like for the pioneers. Back then, even talting a simpleporhait was a major undertaking.At the end ofthe rgth century, a photographic safariwas often a fir1i-blown expedition, withateam ofportersmanhandling enormous brass'bound cameras, healylenses, sensitised glass plates, plate-holders, hefty tripods,a portable darkroom and developing chemicals in giasscontainers. Not to mention tents, guns (for protection andito provide a supply offresh meat), cooking pots and amountain of other gear sufficient to last a year or more.Even in their wildest dreams, those trailblazers couldnhave imagined how easy photographers have it today. qNone oftheir images would win our competitions, butthose foi.rnding fathers (and th ey were mirly men) wereremarkable for their time. They enthralled a wide-eyedpublic that had never before seen photos of wild animals.ltCHALLENGES AND BREAKTHROUGHSa\;The genesis ofphotography as we now know it was in1826, when foseph Nic6phore Ni6pce producedthe firstpermanent photograph on a metal plate coated withbitumen. Wildhfe photography was born a little 1ater, inthe early r86os, when a hand6-rl ofpeople began takingpictures of domestic and zoo animals.Some images from this period - such asthe poignant photo oflondon Zoo s lastquagga, taken by rr'1 unkl6pn photographerin the early r87os - are widely reproduced toLhis day. The oldest survivixg portrait of awild animal is probabiy one of a white storkon its nest in Strasbourg, photographed inr87o by an American, Charles A Hewins.One of the greatest challenges at this timewas the heary, unwieldy equipment, which,,,made wildlife photography an essentiallystatic endeavour. This is why most people )

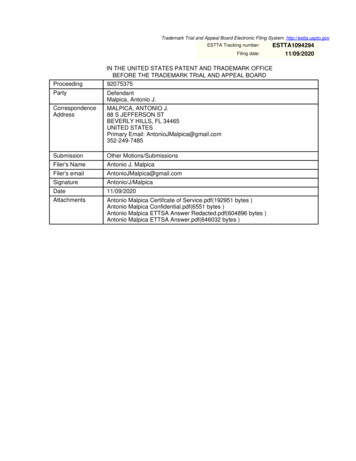

This perfectlycomposed barn.','owl photo,from1936, is oneofthe most famousimagei taken by;"- .celebrated bird#i.'photographer EricHosking (below).concentrated on photographing birds at or near the nest.In the mid-r89os, RB Lodge and his young assistant, OliverPike, used to push a rz x ro-inch plate camera around theEnglish countryside in a wheelbarrow. But Pike became sofrustrated with all the pushing that he developed his own'Bird-land Camera, which was portable enough to be usedfor stalking as well as from static hides.By now, wildlife photographs were already appearing inbooks and joumals. Initially, though, what readers saw wasnot the actual photo but the print of a wood engraving. Thiswas prepared by painstakingly translating all ofthe tones of:,:ethe original image into delicateiy engraved lines on wood.COUNTERFEIT CATTLEoBrothers Richard and Cher:ry Kearton.:were perhaps thebestknown oftheearly pioneers. In 1895, inspired bytheir bird-loving grandfather andamateur-naturalist father, who tookthem birdwatching on the Yorkshiremoors, they produced Bitish Birds'Nesfs. It was a landmark - the firstnatural-history title illustrated entirelywith photos instead of artwork.The Keartons devised a number ofnewtedrriques to obtain their reveaiing wildlifeshots. They would stand on one anothelsshoulders, for example, and employ;,.,gxceptionally tall tripods to glirffilodW-,':'. -:.i,s I:ri:-: - iE\ Itoli6&E,}.,8.a. ;"" - lii:':ti:li*:!

I,nxq:r jEa-ffiULLSffiK'Y*THE KEARTGNS ALS& ffiLJELT A LIFE-SIU ffiffiT *L*SE-UPS &F L&CAL BIRDS. UNFSffiYUhXEYMLKffihjg MAYTHE B*GUS ffi*VgE\IE T'OPPt B *VMR,linside birds' nests. But their main innovation was theiruse ofhides. The brothers designed a variety ofingeniousartificial rod s and tree tmnks, erected stone shelters andcovered tents with grass arld heather.Most famously, the Keartons also built a life-size 'builockto get dose-ups oflocal birds. Unfortunately, one dayfuchard became so dizzi after squinting through a sma11peephole for hours (if s uncertain exactly where the openingwas) that he lost his balance and the bogus bovine toppledover. Cherry came to the rescue an hour later, but not beforetaking a photo ofhis brother's predicament - surely one ofthe funniest images of a wildlife photographer at work.The IGartons soon realised that their complex hides wereunnecessary replacing them wiih simple square versionsIil e those sti11 in use today. They went on to publish manysuccessfll nature books showcasing their ground-breakinginduding Will.life Across the World, which featuredan introduction by US president Theodore Roosevelt.pich-rres,FLA I-{Es, FAKN AruM AUT*ffi*E*L SBy the end of the rgth century there were no fewer than256 photographic dubs and an estimated four millioncamera-owners in Britain. There were so many wildlifephotographers (sti11 mostly men), shooting such a rangeof subjects in the wildest corners of the country, that aZoological Photographic Club was established.At around this time, Carl Georg Schillings embarkedon an ambitious proiect to create a pictorial record ofthewiestled with massive, clumsywildlife oflast,tfricaa F

{8" EE!{ln the 1960s,Jacques-YvesCousteau (aboye,foreground) beganto document theundersea realm onfilm, and created aprototype for theNikonos (be/ow),a submersible35mm camera.telephoto lenses (which were incredibly difficult to focus) anddabbied in flash photography. He had to mix the magnesiumflash powder in a mortar immediatelybefore taking eachpicture, itselfa very risky operation. The subsequent explosionsometimes set fire to the hide, or even to his cameras.Schillings nearly gave up on many occasions, but did enjoysome remarkable successes. Take, for example, this elatedentry in his dlary "Almost exactly at midnight my flashlightapparatus gave me a rea1ly hard-to-get nature document:the picture of a magnificent 1eopard."The early rgoos also saw the first acknowledged exampleof 'animal faker/ - a term coined by Roosevelt - when anrlnnamed photographer tied a woodlark to the top of a smalltree and tried to pass his pich.res offas authentic. Apparently,his peers were disgusted and scandalised.During the rgzos and r93os, wildlife photography wasto receive a welcome boost, but this timethe innovation had nothing io do withphotographic paraphemalia. Massproduced motor cars meant sebackandfoot.African expeditions, in particular,became much safer as there was lessrisk ofhaving to shoot an irate rhino,elephant or bufialo. And, since none ofthe big game feared vehides, they couldbe approached more dosely.THE MODERN ERANo history would be complete without a mention of one ofthe true greats: Eric Hosking. His 6o-year career is significantbecause it marks the start ofrecognisably modem wildlifephotography. Hosking was the first to resort to tower hides,in the r93os, and to use electronic flash for bird photography,nry46; he also made a decent living from his photos.One of Hosking's most momentous decisions was hisswitch to the 35mm system (see box, oppositel in 1963. Muchsmaller, tougher and more user-friendly than anlthing thathad gone before, 35mm cameras heralded a new dawn inwildlife photography. They were higtrly portable, ideal forcapturing action and panrring with moving subjects, andwhen modified could even be taken underwater. Ifs nocoincidence that the early r96os also saw the launch of themagazine you are reading now, and the world s leadingwildlife photography contest. The rest, as they say, is history.rfFSCHILLINGS HAD TO MIXTUAGNESIUT\fi FLASH POWDERIN A MORTAR.THE EXPLOSIONSOMETIMES SET FIRE TO THErDE, oR EVEN Hrs CAMERAS" I

85: & M&ffi4ffi ruMfWffiffiffiFn{cr*188Os exposuretimes had also beenthar: amyether desEgn*ffalling dramaticallyeamena, t{re SSrmrsrSLR has shaped tl"*e.cvolutisra *f wildlifeph*tegraptug"- from severalseconds to afraction of a second, - as'wet'platesII ;s pa!aEs!{BThe standardisation of, were replaced by35mm film for motionpicture use in 1909 ledto the development ofstills cameras based onthe same format. Thefirst successful modelwas the Leica A, whichwent on sale in 1925.r dry1plates and film."camera; manufacturers'.' continued to adaptI,forAdvertisements35mnr cameras, suchthis one for a Leica modelfrom 1932 ernphaslsedtheir speed ofThese cameras were morecompact and cost-effective thanthose that used glass plates, andexposures could be made much more rapidlywith them. ln time, they were to transformwildlife photography - a technicallyproblematic genre that frequently involvescapturing fast-moving, distant, dangerous orshy animals in less than ideal light.There were many incremental improvementsto the 35mm camera system, explains ColinHarding, curator of photographic technologyat the National Media Museum. "Longer-focustelephoto lenses meant that photographersdidn't need to get so close to their oftenreluctant subjects, and the introduction ofSLRs during the mid-1930s brought easilyinterchangeable lenses. Meanwhile, since the;::,Iiii::;asand enhancethroughout the 2Oth century.The first 35mm SLR with apentaprism viewfinder waslaunched in 1949' ensuring thatuse.what you saw before pressingthe shutter was what you got on film. ln 1959came the Nikon F, a 'system' SLR that hadinterchangeable components."From the mid-1960s onwards, increasingautomation led to big strides in 35mmcameras," says Michael Pritchard, directorgeneral of the Royal Photographic Society."Autofocus and auto-wind on were keyadvances. And photographic emulsionsimproved, becoming ever more sensitive."Today, of course,35mm film is practicallyobsolete. Kodak produced its last roll ofKodachrome in 2O09. Photography has gonewholeheartedly digital - the new revolution.Sarah Baxter, travel writer and photographerffi,'{ooj:tlsl *nsffiyt3x&"*[ir{iIiiififrow

WILD WOMENSa tur" wildlife photography hasbeen dominated by men. But why?E qajPf dCompared to other genres, wildlifephotography is very, well, male. Clearly,it's physically challenging, and there'san issue of personal safety - a womanworking on location needs to be careful.But is it also inherently macho?"With men, it's a kind of competition,"says Sandra Bartocha, who specialises inphotographing natural landscapes andplants. "The harder it gets, the heavier thebackpack is, the longer the lens and thegreater the adventures, the better thepictures. Women do photography morefor themselves, to express their views.""Men tend to be more aggressive andpushy in the field," adds Africa-basedwildlife photographer Angie Scott, "andmany women find that hard to handle.Also, some guys can be patronising;I try to ignore it. You earn respect byproving you're up to the challenge."There's a lifestyle issue, too. "Thoughthere are lots of women who'd like towork in this business, the practicalitiesare often too much to deal with," admitsAngie. "Having a family is unusual for aprofessional female wi ldlife photographer- and for many women that's a probleml'Sarah BarterWHATNOW?'Ti] ENIXTIOOYIARSMark Carwardine reflects on wildlife photography in2O12,and wonders how it might develop overthe coming century.ildlife photography has changedmore over the past decade thanduring the whole of the previouscentury. And it's ail due to digrtal.To appreciate the scale ofthe transformation,one has only to look at Wildlife Photographer, ofthe Year. The competition first accepted'digial images in zoo4, and was roo per centjust sixyears the industry':digi.tal by zoog - inhad changed beyond recognition.Digital has countless advantages over film.Therds no need to carry around umpteen rollsi:of:Kodachrq.me; you can take manymoresolcan affordto experiment and takendydr.cari adaptyour shooting - andifuar,niigffidi*thitein the field.Where the digital revolution will take us nextis anybody's guess. Technology is advancing inleaps and bounds: cameras that print, projectpicrtres onJo a screen, upload to websites suchas Facebook and take 3D images are either[torr PREDT.TTHAT ITHE CAMERA ITSELFWILL DISAPPEAR,LEAVING A LENS WITHA GHIP AND A SCREENrHE BAGK.Lo*with us or just around the comer. Someexperts even predict that the camera itseHwilldisappear, leaving only a lens with a chip and ascreen on the back. The concept oftaking stillimages might go, too: we may be able to shootdigital video of such high quality that we simplypick our favourite fiames from thousands.alreadyTHE PHOTOGRAPHER RULESLlltimateh though, it doesn t matter whetheryou have the latest DSLR or stick with a trustyplate camera. One thing your kit can neverdo is decide where to point the 1ens, whatto indude in the frame and when to releasethe shutter. That will always be down to you,the photographer - and that's a good thing.I

camera-owners in Britain. There were so many wildlife photographers (sti11 mostly men), shooting such a range of subjects in the wildest corners of the country, that a Zoological Photographic Club was established. At around this time, Carl Georg Schillings embarked o