Transcription

Dr. Eugene Alford had operated on thousandsof patients. When an accident left himparalyzed, he learned about healing fromthe other side. By Michael HaederleEugene'Alford needeci/.to relax after a particularly grueling peribd of work, he'd drive to his raneh'in Bellville, Texas, 70 miles west of hisHouston home, and lose himself in farm chores. He didn't make it out thereas often as he would have liked. As a plastic surgeon at Methodist Hospital,he'd,performed 800 operations over the previous year. December had beenespeeially busy, and he was booked solid in the OR for months ahead.So 0,n G\ chilly Sunday a fe,w days after Christmas, Alford decided to forgochurch imfavor of a spin around his 80-acre property. At the wheel of hisbright-orange tractor, he headed out through the pine bush and mesquite,intending to clear a trail for deer hunting.Whenever119

As he cut through underbrush in thesouth pasture, Alford brought the tractor to a halt in front of a dead whiteoak standing in his path. He nudgedthe trunk with the tractor's front-endloader, expecting the 40-foot tree totopple neatly to the ground. Insteadthe top half of the oak swayed towardhim. In seconds, more than a ton ofhardwood slammed down on him,crushing his spine.Pinned to the steering wheel, AI120ford could barely breathe. He tried tohit the brakes, but his legs failed to respond. When he found he could move 'his hands, he turned off the ignition,then with' great effort pulled his cellphone from his shirt pocket and calledhis wife on speed dial. "Mary," hegasped, "a tree fell on me. My back isbroken. I'm going to die.""Don't quit!" she shouted. "We'recoming to get you!" Alford promised tohold on, but he knew that if he wentreadersdigest.cominto shock, his chances were slim. Theidea of leaving behind his wife andthree teenage children was unbearable.A minute later, he called her back. "Incase I don't make it," he said, "I have totell you that I love you."He closed his eyes and prayed.Gene Alford, 49, grew up in Henderson, a small town in East Texas. Hisgrandfather, John Rogers Alford, wasa successful businessman and philan-thropist, and his father carried on bothtraditions. Alford was raised to workhard and help others. "You didn't tellanybody you did it," he said of his parents' values. "You just did it."After graduating from medicalschool, Alford built a lucrative careeras an ear, nose, and throat specialist anda facial plastic surgeon at Methodist. Inthe summers, he and Mary, a dentistand former pediatric nurse, would joina church-sponsored medical missionto Honduras, where he operated on theneedy in a rural clinic.At .home, Alford treated manyprominent Houston residents, but healso waived his fee for less fortunatepatients. Carolyn Thomas, for instance, went to see him 'with a largegauze bandage over a cavity in herface. She'd been shot by her boyfriend,who'd also killed her mother; the bullet had blown away Thomas's nose,upper jaw, and right eye. Reconstruction would have cost a million dollars,but Alford, his medical team, and hishospital did it for free.Like many of Alford's patients,Thomas valued his empathy almost asmuch as his medical skill. "On dayswhen I was down," she recalls, "he'dsay, 'I know something's wrong. Areyou missing your mother?' I could talkto him about stuff like that." Thomasbecame a spokeswoman for victimsof domestic violence, and Alford appeared with her on The Oprah Winfrey Show and Larry King Live.Now the man who had offered hopeand comfort to so many was fightingto stay alive.3/09121

potentially lethal risk. Alford hadalways been the one to handle bigmedical decisions for the family. "Ithought, He's supposed to be givingme instructions about this," Mary says."I felt horribly alone."After almost two weeks in the lCU,Alford awoke, and his condition improved enough for him to be taken offthe ventilator. He was soon movedacross the street to a rehabilitationunit, where he began physical therapyand learned to use a wheelchair.He confronted his new reality oneafternoon as he watched an NFL gameon TV from his hospital bed. He hadno movement or feeling below hisnavel. His doctors couldn't say if hewould ever recover them entirely. "IAlford was still conscious when hisneighbors Kevin Wingo and SnuffyGarrett, alerted by Mary, hauled thetree off him. They Were afraid thatdoing so would make Alford's injuriesworse, but they went ahead when besaid he'd die if they didn't. A rescuehelicopter touched down minuteslater, and Alford advised the paramedics on which drugs to administerto him. Then he blacked out.He was flown to the trauma unit atMemorial Hermann-Texas MedicalCenter in Houston, then quickly transferred to Methodist. The tree hadsmashed Alford's T4 vertebra anddamaged several others. His lowerback had been bent so sharply that itpinched off the blood supply to thespinal cord, paralyzing him from the122waist down. He'd also broken his collarbone and shoulder and eight ribs.That night, Mary took John, 19,Bess,17,and Charles, 15,to see their fatherin the lCU. Alford murmured reassurances, then passed out again. Thefamily set up a vigil by his bedside.The next evening, an orthopedic spinespecialist fused the vertebrae in Alford's middle back and reinforcedthem with titanium rods.The operation was successful, butthe patient was still in danger. BecauseAlford's lungs were bruised, doctorswanted to perform a tracheotomy andhook him up to a ventilator. With Alford still unconscious, it was up toMary to give consent. She also okayed.placing a filter in a vein near his heartin order to trap blood clots, anotherreadersdigest.com3/09wondered, Will I ever be able to goback to work?" he recalls. "Will I beable to be a surgeon again? Will I beable to be a husband and father?"In February 2008, six weeks after theaccident, Alford returned to his100-year-old home in Houston. Atfirst, he was so weak that he could situp only when strapped into a wheelchair; Mary lifted him in and out ofit using a sling attached to an electricw.inch. In constant pain and withfrequent muscle spasms, he spent histime in a bed set up in the family room."Every day was exactly the same,"Mary says. "Every bit of our energywas focused on just surviving."Before the accident, Alford had been

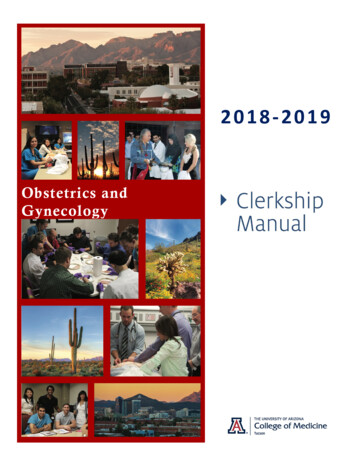

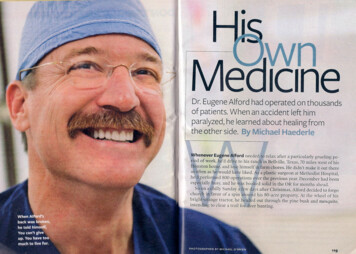

cided you liked work more than us,"Mary told him one day over lunch."But now I realize you didn't want toleave the hospital because there wereso many folks that needed you. Youcouldn't just abandon them."Alford was moved by his wife's un. derstanding-andgrateful for onething about the accident: It gave him anopportunity to focus on the people heloved most. When Mary wheeled himto the garage for a shower that she gavehim by hose, or when one of his children helped him dress in the morning,Alford says, it was as if God had usedthe accident to send him a message:"You need to slow down and appreciate what you've got at home.""Some of my happiestmoments have been inthe operatingroom,"says Alford, shownperformingsurgeryfrom his wheelchair.a solidly built six-footer and was usedto being in charge. Now, entirely dependent on others, he fell into despair."If it weren't for my wife and kids, Iwould have killed myself," he says.But then the love started pouringin. Alford's brother David, 40, a businessman in Henderson, maintained ablog to provide updates about Alford'srecovery. Over the next three months,124he received a staggering 40,000 messages from colleagues, former patientsand their families, acquaintances, evenstrangers. Carolyn Thomas wrote,"When you're back in the OR, I wantto be the first one on the table."Friends took hot meals to the AIfords every evening and drove Charlesto school and to lacrosse and otheractivities. One woman at church gavereadersdigest.comthe family a wheelchair-ready van thathad been used by her late husband."Anything I've done for other peoplehas been repaid to me a million timesover," Alford now marvels.The outpouring raised his spirits. Italso gave Marya new perspective onhim. For years, Alford's schedule ofIS-hour days hadn't left him much timefor her and the kids. ''I'd just about de-The couple refurbished their housewith ramps, a wheelchair-accessiblebathroom, and an elevator. Theybought an extended-cab pickup truckand fitted it with a wheelchair hoist, aswiveling driver's seat, and hand controls so Alford could drive himself.But Alford's goal was to make suchadjustments temporary. After a monthof physical therapy, he graduated froman electric to a manual wheelchair.One day last winter, he wiggled histoes. "It was huge," he remembers."Mary and I just cried and cried,we were so happy." More sensationand movement returned in his legsand feet.The daily workouts built strengthin his back and abdominal muscles,improving his ability to hold himselfupright. Soon he was able to standwith the aid of a tubular steel frame;3/0912"

"If I'd been alonethrough this, Iwouldn't be heretoday," saysGene, picturedwith Mary.seated in his chair, he could now drawhis legs toward his chest. In May, Alford began the next phaseof treatment-an experimental regimendeveloped by the Christopher & DanaReeve Foundation. Each morning, hewent to the Institute for Rehabilitationand Research at Memorial Hermann.By putting a paralyzed patient throughhis paces, therapists hoped to grow newneuromuscular connections.When Alford arrived at the clinic,a physical therapist and a team of assistants would strap him into a har126ness suspended above a treadmill.They swung his legs at a steady paceas Alford, eyes fixed on a full-lengthmirror, struggled to help by lifting athigh with each stride.After three months of this routine,Alford's coordination had improvedmarkedly. He felt ready to pick up ascalpel again, with the hospital's approval. He started small, with an office procedure on a friend's son whohad injured his nose. The operation·went smoothly. A few days later, usinga wheelchair specially designed to liftreadersdigest.com3/09him into position, he joined a colleaguein performing an hour-long optic nervedecompression at Methodist. "It feltwonderful," Alford says with a smile."It was just so good to be back in thatenvironment."Still, his limitations were never farfrom his mind. On the night that Hurricane Ike struck Houston withllOmph winds, Alford's bedroom windowexploded, showering him and Marywith glass. "I watched my wife and myIS-year-old son use a card table, a BoyScout tent, and duct tape to cover thewindow," he says. "I realized that I wasdifferent forever. I also realized thatMary was different forever-andshecould handle it."Alford still goes for four hours ofrehab every morning and spends hisevenings stretching and riding a motorized stationary bike to keep muscle spasms at bay. But in the hoursbetween, he sees patientI' or performssurgeries-asmany as five a week."My stamina has come back," he says."I don't hurt like I used to."On a recent afternoon in a MethodistHospital operating room, he repairedREALITYthe deviated septum of Darren DeFabo, a 40-year-old Houston engineer.Leaning in from his elevated chair, Alford cut through the bone and cartilage, working quickly and methodically,occasionally exchanging a commentwith a nurse or a surgical tech.With Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Fortunate Son" playing in thebackground, Alford sutured in temporary splints to support his patient'snose after the operation. In all, theprocedure took 22 minutes. "It wasvery normal, embarrassingly simple,"Alford remarked as he wheeled himself out of the OR.He's eager to do more complex surgeries and plans to increase his workload. Walking remains uncertain. "Ialways tell him if! had a crystal ball,I'd be a millionaire," says Marcie Kern,one of his physical therapists. Still, thedoctor considers himself a lucky man."I wondered if I could practice medicine as well as I used to, and I thinkI've answered that question," Alfordsays. "My brain works, my hands work.I'm closer than ever to Mary and mychildren. I've got so much. Whyshould I feel sorry for myself?"CHECKBill Maher is getting sick and tired of body modification. "Just because yourtattoo has Chinese characters in it doesn't make you spiritual," he argues."It translates to 'beef with broccoli.' ""The big oil companies must stop running ads telling us how muchthey're doing for the environment:' rants Maher. "If you folks at Shell arereally serious about cleaning something up, start with your restrooms."From New Rules by Bill Maher(Rodale)712

readersdigest.com 3/09 himinto position, h ejoin d a coll agu in performing an hour-long optic nerve decompression at Methodist. "It felt wonderful," Alford says with a smile. "It was just so good to be back in that environment." Still, his limitations were never far from his mind