Transcription

LEARNING FROM PR ACTICE SERIES J U N 2 013Life Skills: What are they, Why do theymatter, and How are they taught?“[Life skills training]has helped usknow how to talk topeople.”Liberia EPAG traineefrom Doe CommunityWhat Are Life Skills?Life skills programs are designed to teach a broadset of social and behavioral skills—also referredto as “soft” or “non-cognitive” skills—that enableindividuals to deal effectively with the demands ofeveryday life. Programs can build on any or all ofthe following skills: decision-making (e.g. critical and creativethinking, and problem solving);community living (e.g. effective communication, resisting peer pressure, building healthyrelationships, and conflict resolution);personal awareness and management (selfawareness, self-esteem, managing emotions,assertiveness, stress management, and sexual and reproductive health behaviors andattitudes).Life skills programs can empower and guidelearners to think critically about how gender normsand human rights govern their interactions with others and affect their behaviors, which is a feature ofthe Adolescent Girls Initiative (AGI) Pilots.These skills can be particularly important duringadolescence, which is filled with new feelings, physical and emotional changes, excitement, questions,and difficult decisions. It is also a time when thedifferences between young men and women becomemore pronounced and gender norms take a strongerhold in governing young people’s aspirations andbehaviors. As they move through adolescence, lifeskills can help young people overcome the challengesof growing up and improve the quality of their youngadult lives. Unfortunately, not much is known abouthow malleable these skills are at different ages orif there are important differences across the sexes.However, it is generally acknowledged that theseskills can be augmented at least up until the endof the teenage years1, and that they are importantfor both young men and women.Life skills programs move beyond providinginformation. Although it is important to deliverinformation and to reinforce such knowledge periodically, this alone is rarely enough to motivatepeople to change behavior. Life skills programsaim to develop young peoples’ abilities and motivations to make use of all types of information. Theapproach should be interactive, using role plays,games, puzzles, group discussions, and a variety ofother teaching techniques to keep the participantwholly involved in the sessions.Why Do Life Skills Matter?LIFE SKILLS MATTER FOR HEALTHOUTCOMESEconometric analysis shows that non-cognitiveabilities (e.g. self-control, sociability, and so forth)explain a variety of correlated risky behaviors andoutcomes such as teenage pregnancy and marriage,drug use, and participation in illegal activities.2 Thepublic health literature finds that young people withgender equitable attitudes have better sexual healthoutcomes than their peers, and the converse is alsotrue. For example, young people who believe thatmales should be “tough” and more powerful thanfemales are less likely to use condoms or contraception, more likely to have multiple sex partners,

2AGI LEARNING FROM PR ACTICE SERIESand more likely to be in intimate relationships thatinvolve violence.3LIFE SKILLS MATTER FOR EDUCATIONAND LABOR MARKET OUTCOMES“I’ve never taken aclass like this before—it is so useful—nowI know the real skillsyou need for life.”Nepal AGI trainee fromoutside KathmanduEconometric and psychology studies in developedcountries suggest that non-cognitive skills canaffect both education and labor market outcomesin developed countries.4,5,6,7 However, much less isknown about how to develop these skills and aboutthe impacts of comprehensive (vocational/technicaland life skill) training programs.Comprehensive interventions to improve youthemployability and human capital were first introduced in developing countries in the early to mid1990s with the Jóvenes programs in Chile, Venezuela,Argentina, Paraguay, and Peru, and later replicatedthroughout Latin America. Experience from theseyouth training programs suggests that life skills area key complement to increase the effectiveness ofvocational skills.8 There have been a number ofrigorous evaluations of comprehensive interventions,however the evaluation designs have focused onmeasuring the impact of the total program package on non-cognitive, behavioral, and employmentoutcomes, rather than the stand-alone impact of thelife skills component.9,10,11The Jordan AGI measured the direct impactof training in a sub-set of life skills focused onemployability among community college graduates(see Table 1 for more program details). A rigorousimpact evaluation of the intervention found thatthe life skills training had no average impact onemployment (1 year later), although there is aweakly significant impact outside the capital city.12The life skills training did improve positive thinkingand mental health among the beneficiaries. It is notknown why the life skills training did not work inJordan, although it is thought that structural issuesin the labor market interfered with the effectivenessof the project.More research is needed to understand boththe direct and indirect effects of life skills programs.Life skills programs might matter on their own, andthey may have an interaction effect for vocational/technical skill training programs to be effective. Thisevidence is particularly important for policymakinggiven that life skills programs can be implementedfor approximately one-half to one-third of the costof a full vocational course.13 More research is alsoneeded to understand the mechanisms throughwhich life skills training can improve youth laboroutcomes and to improve the instruments used tomeasure such skills.14How Does the AGI Teach Life Skills?There are many different models for implementinglife skills programs—whether formally throughschools, informally through community organizations, or—as in the AGI—in the context of a programdesigned for another purpose (e.g., livelihoods,vocational training).15 Life skills programs—or inthe case of Lao PDR and Jordan, a subset of theseskills focused on employability—are incorporatedinto all of the AGI pilots. Typical duration of programswithin AGI pilots is approximately 40 hours overthe course of several months. For each of the AGIpilots, Table 1 summarizes (i) the key steps in thecurriculum development; (ii) the training content;and (iii) the implementation model.16 This sectionsynthesizes key lessons learned from the AGI pilotson how to design and implement a life skills program.Lesson Learned: Adapt life skills programs for local lives.An assessment of the community and the targetaudience should be conducted to help tailor thelife skills program to specific local needs. If avulnerability study was conducted to inform theproject design, this analysis can also help identifykey issues to include in the life skills curriculum.Other organizations that may also be teaching lifeskills should be consulted to see if locally-adaptedcurriculums already exist. If not, international bestpractices can be drawn on to develop the programcontent, but then adapt sessions to make them moreappropriate to the local culture.17 This may entailtranslating the curriculum into local languages,changing names or situations in role plays, and adding or discarding certain modules. The curriculummay need to be updated on a regular basis to remainrelevant. Remember to think carefully about the ageand literacy levels of the beneficiaries. Curriculumsworldbank.org/gender/agi

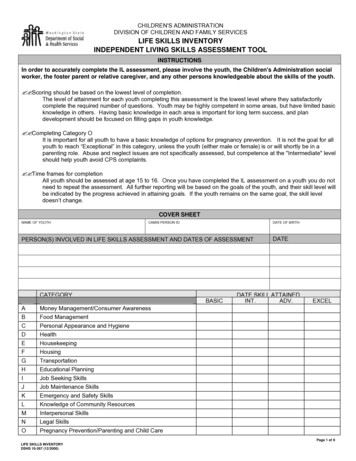

3Table 1: Life Skills in the AGI PilotsContentImplementation Curriculum developed by the Banktask team based on internationalexperience. Informed by consultations withadolescent girls. Local consultant hired to adapt thecurriculum. Vetted among Government Ministries. Psychosocial educationCivic engagement and leadershipSex, gender and violenceSexual and reproductive healthPreparing for workReducing risks related to naturaldisasters Financial literacy Implemented by CBO’s and technicaltraining providers. Curriculum developed by BusinessDevelopment Center (BDC), aJordanian NGO. Informed by consultations withemployers. Effective communication and businesswriting skills Team-building and team work skills Time management Positive thinking Customer service CV and interview skills Implemented by BDC. 45 hours over a 9 day period (5 hoursper day), with a maximum of 30participants per group. Sessions held during daylight hours atlocally known and trusted institutionssuch as the Chambers of Industry andlocal universities. Curriculum developed by serviceproviders with EPAG coordinationteam. Informed by “Girls VulnerabilityAssessment” conducted prior toproject implementation. Adapted from several resources, bothin-country and international. Preparing for the world of workSexual and reproductive healthFamily skillsHealthy livingPreventing and responding to SGBVCommunication, self-esteem, andleadership Know your rights Community service Implemented by EPAG serviceproviders (a mix of Liberian andinternational NGOs). Classroom training phase runs for sixmonths. Training tracks vary: 3–4 hoursper day, 3–4 days per week. All classes held during daylight hoursat training venues in communitieswhere trainees reside. Curriculum developed by the Centrefor Development and PopulationActivities (CEDPA). Consultant hired to tailor thecurriculum for the target group ofthe AGEI and field test with the T&Eproviders. Classroom training is 40 hours over 5days following the technical training. The T&E providers subcontractspecialized trainers to deliver the lifeskills training. Trainers trained via a training oftrainers (ToT) model, with a refreshercourse.South SudanNegotiation skillsDealing with discriminationWorkers’ rights educationSexual and reproductive healthBusiness development skills andfinancial management Curriculum developed by BRAC based Skills of making effective decisions Course is conducted over 5 monthson a similar AGI project in Uganda, Skills of knowing and living with others(20 hourly sessions) within the Girlsand adapted to the South Sudan Skills of knowing and living withClub premises.environment.oneself Adolescent Girl Leaders trained by Sexual and reproductive healthBRAC to deliver the life skills via a(menstruation, early pregnancy, STI/training of trainers (ToT) model, with aHIV prevention, family planning, etc.)mid-way refresher course. Leadership Gender and bride price Rape (meaning, prevention strategies,responding and coping)Lao PDRNepalLiberiaJordanHaitiDevelopment Local firm hired to provide certifiedtraining on counseling and soft skillsto career counselors. Training session and materials werethen developed by the counselors,informed by a needs assessmentamong students. Team work skillsNegotiation skillsProblem solvingCV and interview skillsworldbank.org/gender/agi 1–2 day training with co-ed classes. Implemented by career counselors atthe National University of Laos andPakpasak Technical College.

4AGI LEARNING FROM PR ACTICE SERIESshould incorporate pictures and images to deliverinformation to less literate audiences. The life skillscurriculum should be piloted in various settings toensure that it is appropriate for the target group.Lesson Learned: Nurture a supportive communityenvironment where beneficiaries can exercise their life skills.“Before the training Iwould never stand infront of a group andspeak but that nowI am comfortable todo it.”Nepal AGI traineefrom BirgunjMost life skills curriculums deal with sensitiveissues like sexual and reproductive health. Theyalso deal with aspects of community life, seekingto influence gender norms and create awarenessaround the responsibilities and rights of living ina community. The project should help to build asupportive environment in which beneficiaries caneffectively exercise their new skills. If the project isworking with younger beneficiaries, it is important tofamiliarize parents with the project and to get theirbuy-in and consent. Projects can engage families andcommunities through community events, workshopsand meetings. In Liberia, AGI beneficiaries have heldcommunity performances demonstrating some oftheir life skills through role-plays.Lesson Learned: Designate safe spaces that are conducive tolearning life skills.Life skills programs should be delivered in spacesthat are suited to the sensitive processes of buildingsocial and behavioral skills. This means that the spaceshould be physically safe for beneficiaries to gatherin and travel to and from. It should also be a comfortable place for beneficiaries to explore life skillstopics in a confidential manner. In South Sudan, lifeskills are delivered in adolescent girl clubs in projectcommunities—reports from project beneficiariesand staff indicate that these safe spaces are criticalfor implementing the project activities. The timingof classes matters too—in Haiti, community-basedorganizations administer the classes on weekendsin community safe spaces to minimize interferencewith girls’ work schedules and household duties.worldbank.org/gender/agi

5Lesson Learned: Carefully select life skills trainers.The local context will affect the characteristics ofwho is needed to implement the program (age, sex,experience, etc.). It may be appropriate to have allfemale trainers—as in South Sudan—or to requirethat all male trainers are paired with a femaletrainer—as in Nepal. Projects should establishcodes of conduct (professionalism, respectfulness,etc.) for trainers, and enforce them through diligentmonitoring. In Liberia, the training delivery is guidedby the principle of “Do No Harm,” meaning thattrainers should only train on topics that they knowvery well. Service providers should ensure thatfacilitators are well-versed on topics in which theytrain. If the curriculum is addressing very specific orsensitive topics, it may be important to work withlocal organizations to implement certain modulesof the curriculum or to participate as expert guestspeakers. In Liberia, several organizations providedvolunteer guest speakers on life skills topics, andguest speakers were also recruited from the project’sPrivate Sector Working Groups.Lesson Learned: Strengthen the capacity of trainersthroughout the program.The project should familiarize the recruited trainers with the content of the curriculum and practiceinteractive teaching techniques. In South Sudan andNepal, the AGI built a cadre of life skills trainersthrough a “training of trainers” system. This modelof cascade training is often an efficient and costeffective way to transfer knowledge and skills tonewly recruited trainers. Several of the AGI pilotsoffer refresher courses mid-way through implementation. Peer educators may or may not be appropriate,depending on the context and the program content.Projects should ensure there will be adequate support for peer educators before embarking on sucha program.worldbank.org/gender/agi

6AGILEARNING FROM PR ACTICE SERIES Lesson Learned: Life skills are built, not taught.Life skills need to be practiced in order to be learned.Delivery of life skills programs is based on activeparticipation and cooperative learning as opposedto lectures. The AGI pilots use innovative teachingtechniques, such as: Guest speakersGroup work and discussionsRole plays and theatreEducational games Story-tellingDebatesArts and musicField tripsCommunity service projectsSporting eventsA good life skills program will foster socialcohesion among the beneficiaries and empowerthem to take charge of their own learning.Lesson Learned: Help spread the spill-over benefits of a lifeskills program.A locally-adapted life skills curriculum can be auseful public good. Projects should disseminate andshare the curriculum with government stakeholdersand other development partners. If the communitygets energized, leaders may even start programswithin their own groups—in churches, women’sorganizations, etc. Likewise, a cadre of specializedlife skills trainers can be of value to other programswith similar goals.worldbank.org/gender/agi

7Summary Checklist for Designing and Implementing a Life Skills Program Has the program perform an assessment of the community and the target audience to helptailor the life skills program to specific local needs? Has the program consulted with other local organizations and referred to international bestpractices to develop the program content? Has the life skills curriculum been piloted in various settings to ensure that it is appropriatefor the target group and the context? If the program is working with youth, has the program informed parents and guardians aboutthe program content and gained their informed consent? Is the content and length of the curriculum realistic to implement? Has the program designated safe spaces where the life skills program will be implemented? If the program is working with males and females, is it appropriate to hold same-sex sessionsfor all or portions of the program? Who is needed to implement the program (consider age, sex, experience, etc.)? Will the program conduct trainings for the trainers and also consider offering periodic refreshercourses for trainers? How will the program support trainers to implement programs in an interactive fashion andfully engage learners in the program? Will the program disseminate and share the curriculum with government stakeholders andother development partners? Can the program evaluate the impact of the life skills program? Scant evidence—particularlyrigorous evidence—is available on the impact of life skills (for labor market, health and variousbehavioral outcomes), delivery mechanisms for teaching life skills, and cost-benefit analysisof programs.worldbank.org/gender/agi

8AGILEARNING FROM PR ACTICE SERIES Endnotes1.2.3.4.5.6.7.8.9.Brunello G and M Schlotter. 2011. “Non Cognitive Skillsand Personality Traits: Labour Market Relevence and theirDevelopment in Education & Training Systems.” DiscussionPaper No. 5743. Bonn: IZA.Heckman J, J Stixrud and S Urzua. “The Effects ofCognitive and Noncognitive Abilities on Labor MarketOutcomes and Social Behavior.” Journal of LaborEconomics 2006 v24(3), 411–482.Cited from: The International Sexuality and HIVCurriculum Working Group. 2009. It’s All One Curriculum.New York: The Population Council, page 15.Heckman J, J Stixrud and S Urzua, 2006.Brunello G and M Schlotter, 2011.Farrington, C.A., et al. 2012. “Teaching Adolescents toBecome Learners. The Role of Noncognitive Factors inShaping School Performance: A Critical Literature Review.”Chicago: University of Chicago Consortium on ChicagoSchool Research.Heckman J and T Kautz. 2012. “Hard Evidence on SoftSkills.” NBER Working Paper 18121.Personal communication with Wendy Cunningham, citedin: Katz, Elizabeth. 2008. “Programs Promoting YoungWomen’s Employment: What Works?” Washington DC:The World Bank.Ibarraran, P., et al. 2012. “Life Skills, Employabilityand Training for Disadvantaged Youth: Evidence from aRandomized Evaluation Design.” Discussion Paper No.6617. Bonn: IZA.10. Bandiera, O., Buehren, N., Burgess, R., Goldstein, M.,Gulesci, S., Rasul, I. and Sulaiman, M. 2012. “EmpoweringAdolescent Girls: Evidence from a Randomized ControlTrial in Uganda.”11. Betcherman, G., et al. 2007. “A Review of Interventionsto Support Young Workers: Findings from the YouthEmployment Inventory.” SP Discussion Paper No. 0715.Washington DC: The World Bank.12. Groh M, N Krishnan, D McKenzie and T Vishwanath.2012. “Soft Skills or Hard Cash? The Impact of Trainingand Wage Subsidy Programs on Female Youth EmploymentPrograms in Jordan.” Policy Research Working Paper 6141.Washington DC: The World Bank.13. Martinez, S. June 2011. “Impacts of the DominicanRepublic Youth Employment Program: Hard Skills or SoftSkills: Intermediate Impact Results.” Powerpoint deliveredat the World Bank–SIEF Working Camp in Washington, DCon April 19th, 2010.14. Ibarraran, P., et al., 2012.15. See http://www.unicef.org/lifeskills/index resources.htmlfor life skills implementation models.16. The Afghanistan and Rwanda AGIs will include life skillsbut the program design is not yet determined.17. Examples include: Advocates for Youth’s Life PlanningEducation Manual; PATH’s Adolescent Reproductive Healthand Life Skills Curriculum; Population Council’s It’s AllOne Curriculum; CEDPA’s Choose a Future: A Sourcebookof Participatory Learning Activities; HDN and Ipas’s Genderor Sex: Who Cares?; and Peace Corps’ Life Skills Manual.The World Bank’s partners in the AGI are the Nike Foundation and the governments of Afghanistan, Australia, Denmark, Jordan, Lao People’sDemocratic Republic, Liberia, Nepal, Norway, Rwanda, Southern Sudan, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. This brief features work by the WorldBank’s Gender and Development Department in the Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Network . For more information about theAGI please visit www.worldbank.org/gender/agi.1323447

differences between young men and women become more pronounced and gender norms take a stronger hold in governing young people’s aspirations and behaviors. As they move through adolescence, life skills can help young people overcome the challenges of growing up and improve