Transcription

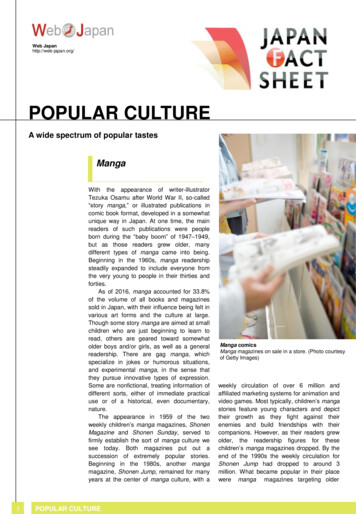

Web Japanhttp://web-japan.org/JAPANESE LANGUAGEA rich blend of outside influence and internal innovationCalligraphyCalligraphy is an artform in which the aim isto use brush and ink tobring out the beauty ofthe characters. (Photocourtesy of GettyImages)IntroductionAs of 2019, Japan's population stood at about126.14 million, and linguistically it is a nearlyhomogenous nation and most of thepopulation using the same language. Thismeans that the Japanese language is theninth most spoken language in the world.However, the language is spoken in scarcelyany region outside Japan.There are many theories about the originof the Japanese language. A number ofscholars believe that syntactically it is close tosuch Altaic languages as Turkish andMongolian, and its syntactic similarity toKorean is widely acknowledged. There is also1JAPANESE LANGUAGEevidence that its morphology and vocabularywere influenced prehistorically by the MalayoPolynesian languages to the south.The Japanese writing system comes fromChinese, although the languages spoken bythe Japanese and Chinese are completelydifferent. After Chinese writing was introducedsometime in the fifth or sixth century, it wassupplemented by two phonetic scripts(hiragana and katakana) that were transformedfrom the Chinese characters.A large number of local dialects are stillused. Whereas standard Japanese, which isbased on the speech of Tokyo, has beengradually spreading throughout the countryunder the influence of media such as radio,television, and movies, the dialects spoken bythe people of Kyoto and Osaka, in particular,

continue rs of Spanish and Italian will find thatthe short vowels of Japanese—a, i, u, e, o—are pronounced very similarly to the vowels ofthose languages. Long vowels—aa, ii, uu, eior ee, oo—are produced by doubling thelength of the short vowels (although ei is oftenpronounced as two separate vowels). Thedistinction between short and long vowels iscrucial, as it changes the meaning of a word.The consonants are k, s, sh, t, ch, ts, n, h,f, m, y, r, w, g, j, z, d, b, and p. The fricativesh (as in English “shoot”), along with theaffricates ch, ts, and j (as in English “charge,”“gutsy,” and “jerk,” respectively) are treatedas single consonants. The g sound is alwaysthe hard g of English “game,” not thatof ”gene.”A major difference from English is thatJapanese has no stress accent: equal stressis given each syllable. And whereas Englishsyllables are sometimes elongated, inJapanese, strings of syllables are spoken withthe regularity of a metronome. Like English,Japanese does have a system of high andlow pitch accents.GrammarAs for basic structure, the typical Japanesesentence follows a pattern of subject-objectverb. For example, Taro ga ringo o tabetaliterally means “Taro an apple ate.”Japanese often omit the subject or theobject—or even both—when they feel that itwill be understood from the context, that is,when the speaker or writer is confident thatthe person being addressed already hascertain information about the situation inquestion. In such a case, the sentence givenabove might become, ringo o tabeta (“ate anapple”) or simply tabeta (“ate”).In Japanese, unlike English, word order2JAPANESE LANGUAGEdoes not indicate the grammatical function ofnouns in a sentence. Nor are nouns inflectedfor grammar case, as in some languages.Grammatical function is instead indicated byparticles that follow the noun, the moreimportant ones being ga, wa, o, ni, and no.The particle wa is especially important,because it flags the topic or theme of asentence.There is no indication of either person ornumber in Japanese verbal inflections. In themodern language, all verbs in their dictionaryforms end in the vowel u. Thus in English itwould be said that the verb taberu means “toeat,” although actually it is the present tenseand means “eat/eats” or “will eat.” Some otherinflectional forms are tabenai (“does not eat”or “will not eat”), tabeyo (“let’s eat” or“someone may eat”), tabetai (“want/wants toeat”), tabeta (“ate”), tabereba (“if someoneeats”), and tabero (“eat!”).Written JapaneseWhile the Chinese use their characters orideograms to write each and every word, theJapanese devised two separate forms ofphonetic script, called kana, to use incombination with Chinese characters. Attimes the written language also containsroman letters—in acronyms such as IBM,product numbers, and even entire foreignwords—so that a total of four different scriptsare needed to write modern Japanese.Chinese characters—called kanji inJapanese—are actually ideograms, each oneChinese characters (kanji)Since 2010, the number of Kanji taught throughoutelementary and junior high school is 2,136.

Street signs use a mix of Japanesecharacters, loanwords and EnglishJapanese incorporates Chineseloanwords and manywords borrowed from English and otherEuropean languages.of which symbolizes a thing or an idea. It iscommon for one kanji to have more than onesound. In Japan, they are used to write bothwords of Chinese origin and native Japanesewords.There are two forms of syllabic kana script.One is called hiragana, which was mainlyused by women in olden times. It consists of48 characters and is used for writing nativeJapanese words, particles, verb endings, andoften for writing those Chinese loanwords thatcannot be written with the characters officiallyapproved for general use.The other kana script, called katakana, isalso a group of 48 characters. It is chieflyused for writing loanwords other than Chinese,for emphasis, for onomatopoeia, and for thescientific names of flora and fauna.Both kinds of kana are easier to write thanthe full forms of the original Chinesecharacters from which they were taken.Although the more complete Japanesedictionaries carry definitions of up to 50,000characters, the number currently in use ismuch smaller. In 1946, the Ministry ofEducation fixed the number of characters forgeneral and official use at 1,850, including996 taught at elementary and junior highschool. This list was replaced in 2010 by asomewhat expanded though similar list of2,136. Publications other than newspapersare not limited to this list, however, and manyreaders know the meaning of considerablymore characters than are taught in thestandard public school curriculum.It is customary for Japanese to be writtenor printed in vertical lines that are read fromtop to bottom. The lines begin at the righthand side of the page, and so ordinary booksusually open from what would be the back ofa Western-language book. Exceptions arebooks and periodicals devoted to specialsubjects—scientific and technical matter—which are printed in horizontal lines and readfrom left to right. Nowadays there is atendency to print books in horizontal lines.These publications open in the same way astheir Western counterparts.Loanwords3JAPANESE LANGUAGEJapanese has not only an abundance ofnative words but also a large number ofwords whose origin is Chinese. Many of theChinese loanwords are today so much a partof daily language that they are not perceivedto have come from outside Japan. Thecultural influence of China over the centurieswas such that many words used in anintellectual or philosophical context are ofChinese origin. When new concepts wereintroduced from the West during the latenineteenth and early twentieth centuries, theywere often translated by making up newcombinations of Chinese characters, andsuch words represent a significant body ofintellectual vocabulary used by modernJapanese.To these loanwords are added manywords borrowed from English and otherEuropean languages. While this coining ofnew words continues, it has been common touse Western words as they are, for example,“volunteer,” “newscaster,” and so on.Japanese also invented such pseudo-Englishwords as “nighter” for night games and“salaryman” for the salaried worker. Thistendency has markedly increased in recentyears.Although the volume of Japan’s loanword“exports” is much smaller than its “imports,” anumber of Japanese words are now infamiliar use in other languages. Examples inEnglish include the following: anime, dojo,futon, geisha, haiku, hara-kiri, judo, kaizen,kamikaze, karaoke, karate, kimono, manga,ninja, origami, ronin, sake, samurai, sashimi,sayonara, shogun, sudoku, sumo, sushi,tempura, and tsunami.Honorific LanguageThe Japanese have developed an entiresystem of honorific language, called keigo,that is used to show a speaker’s respect forthe person being spoken to. This involvesdifferent levels of speech, and the proficientuser of keigo has a wide range of words andexpressions from which to choose, in order to

produce just the desired degree of politeness.A simple sentence could be expressed inmore than 20 different ways depending on thestatus of the speaker relative to the personbeing addressed.Deciding on an appropriate level of politespeech can be quite challenging, sincerelative status is determined by a complexcombination of factors, such as social status,rank, age, gender, and even favors done orowed. There is a neutral or middle-groundlevel of language that is used when twopeople meet for the first time, are not awareof each other’s group affiliation, and whosesocial standing appears to be similar (that is,no obvious differences in dress or manner).Mastery of keigo is by no means simple,and some Japanese are much more proficientin it than others. The almost countlesshonorific terms are found in various parts ofspeech—nouns, adjectives, verbs, andadverbs. So-called exalted terms are usedwhen referring to the addressee and thingsdirectly associated with him or her, such asrelatives, the house, or possessions. Bycontrast, there are special humble terms thatone uses as the speaker, when referring tooneself or things associated with oneself. It isthe distance created by these two contrastingmodes that expresses the proper attitude ofrespect for the person being spoken to.NamesJapanese have family names and givennames, used in that order (while manyEnglish-languagenewspapersandmagazines in Japan present names in theorder common among Western cultures,presenting them with the family name first ispreferred.). When addressing another personit is common to use san—the equivalent ofMr., Mrs. (or Ms.)—after the family name. Thesuffix chan is often attached to children’snames and given names of close friends.Other titles, such as sensei for “teacher” or“doctor,” are also attached as suffixes afterthe family name.Given names and their Chinesecharacters are chosen for their auspicious4JAPANESE LANGUAGEmeanings and happy associations in the hopethat they will bring the child good luck. As of2017, the government has authorized a totalof 2,999 characters for use in given names.Typing Japanese TextTyping in Japanese used to be performed onbulky machines. In 1978, the first Japaneseword processor system went on sale, allowingthe Japanese language to be inputphonetically via a keyboard. When Japanesewords are typed using word processingsoftware, either one of the two kana scripts orthe roman alphabet can be used. Inputmethod editor (IME) software displaysphonetic matches and allows the user toselect the correct characters.The use of keitai (cell phones) to sendtext messages via either e-mail or instantmessaging has become hugely popular inJapan, particularly among young people. Textentry on the cell phone’s small keypad isdone by using the thumb and forefinger topush number keys multiple times to selectcharacters from a particular sequence of kana.Once the kana have been entered they canbe converted to Chinese characters asnecessary. In PC-based messaging there wasalready a tendency to make frequent use ofabbreviations, truncated words, and symbols,and this has further accelerated in keitaimessaging. Japanese has its own extensiveseries of emoticons known as kaomoji (“facecharacters”), and there are also manygraphical emoji (“picture characters”) whichcan be easily embedded in cell phone textmessages in place of words or phrases.As children who grew up communicatingwith short text messages sent via cell phonesand PCs become adults and enter theworkplace, they are changing the way thatwritten Japanese is used, often to the chagrinof their elders.

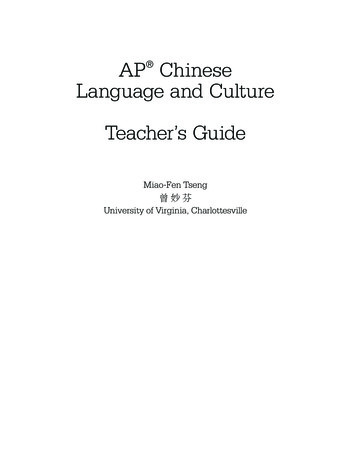

Hiraganaあ いakikかkaうえ おきゃ きゅ きょueokyaきくけこが ぎぐげ ごしゃ しゅ しょkikukekogagigugeshaさしす せ そsashisugoざじず ぜ ぞsesozajizuたちつ てとだtachitsutodatezezoぢ づ でどjizudedoな に ぬ ね のnaninunehahiば び ぶ べ ぼhehobaもぱ ぴ ぷ ぺ ぽmamopamumebipibupubepebopoJAPANESE LANGUAGEchuchoにゃ にゅ にょnyanyunyohyuhyoみゃ みゅ みょmyamyumyoりゃ りゅ りょryaryuryoゆよyayuyogyaじゃ じゅ じょらりる れろrariruroreわをwawoぎゃ ぎゅ ぎょjagyujugyojoびゃ びゅ びょbyabyubyoぴゃ ぴゅ ぴょn5chaやんKatakanashoちゃ ちゅ ちょhyaま み む めmifushukyoひゃ ひゅ ひょnoは ひ ふ へ ほkyupyaアイウエオakikueoカキクケコガ ギ グ ゲ ゴkakikukekogaサ シスセソsasusesoshipyupyoキャ キュ キョkyagigegoザ ジズ ゼゾzazuzojiguzekyukyoシャ シュ ショshashushoチャ チュ チョchachuchoタチツテトダ ヂ ヅ デドtachitsutetodadoナニヌネノヒャ ヒュ ヒョnaninunenohyaハヒフヘ ホバ ビブ ベ ボミャ ミュ パ ピプ ペ ポmamimumemopapuヤユヨyayuyoラリル レロrariruroreワヲwawopipepoニャ ニュ ニョnyanyuhyumyunyohyomyoリャ リュ リョryaryuryoギャ ギュ ギョgyagyugyoジャ ジュ ジョjajujoビャ ビュ ビョbyabyubyoンピャ ピュ ピョnpyapyupyo

JAPANESE LANGUAGE A rich blend of outside influence and internal innovation evidence that its morphology and vocabulary were influenced prehistorically by the Malayo- Polynesian languages to the south. The Japanese writing system comes from Chinese, although the languages spoken by the Japanese and Chinese are completely different. After Chinese writing was introduced sometime in the