Transcription

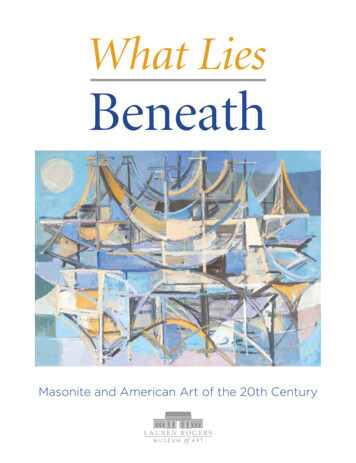

Masonite and American Art of the 20th Century

Masonite and American Artof the 20th CenturyIn the early years of the last century, technologywas providing artists with resources that were asnew as their modern styles. Masonite was one ofthe most prevalently used of the new materials.This manufactured hardboard, which lies beneaththe paint of innumerable 20th century artworks,was invented in Laurel, Mississippi, in 1924 byWilliam H. Mason. In celebration, the Lauren RogersMuseum of Art, founded in Laurel in 1923, presentsthis exhibition of American paintings on Masonite.As the material was an invention of the South,we have gathered work from several Southernmuseum collections, including our own, and manyof the featured artists have ties to our region. Theexhibition and this accompanying publication tellthe story of William H. Mason, the invention of hishardboard, its numerous applications, and the waysin which artists and art restorers used it in the 20thcentury.2

William Horatio Mason (fig. 1) was bornin Summer County, Virginia in 1877, andin 1884 his family moved to Lewisburg,West Virginia.1 After being educated byprivate tutors, he attended the VirginiaMilitary Institute and Washingtonand Lee University. In 1896, he wentto Cornell University in Ithaca, NewYork, leaving two years later to servein the United States Navy during theSpanish War as an engineering officer.After the war, in 1899, Mason became adraughtsman at the Edison Laboratoriesin West Orange, New Jersey. He workedin various capacities and locationsfor Edison until 1916, when he took aposition as General Superintendent incharge of construction at the MerchantsShipbuilding Corporation in Bristol,Pennsylvania. Next, he worked at GeneralMotors in Detroit to develop a hydraulictransmission for automobiles, for whichhe acquired patents.While working for Edison, Mason marriedMarian Alexander Dana, whose familybusiness was the Wausau-SouthernLumber Company. Based in Wisconsin,the company followed in the footstepsof the Eastman, Gardiner, and Rogersfamilies from Iowa, and began buyinglarge tracts in the Piney Woods ofMississippi. These Midwest industrialistsopened mills in the town of Laurel,which became known as the “YellowPine Capital of the World.” While onvisits to the Wausau-Southern sawmill inLaurel, Mason noticed the large amountsof waste materials produced by thelumber business, including sawdust,wood chips, and resin. Determined toFig. 1: Nicholas Basil Haritonoff (Russian/American, 1884-1944), William H. Mason, 1939,oil on Masonite, Collection of Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Gift of Charles White Gamble,78.7find uses for these waste products, in1920 he moved his family to Laurel tobuild an experimental plant to extractnaval stores, such as turpentine andpine oil, from sawn lumber. Financed byWausau-Southern, he built a number ofthese plants in the South. The businesseventually turned unprofitable due todeclining demand for naval stores duringthe postwar years and the fact that thelumber mills were running short of pine.During his years in the shipbuildingindustry, Mason had been intrigued bythe capability of wood to bend whensubjected to steam. Moreover, he wantedto find a use for the waste wood slabsand edgings. In the early 1920s, hefocused his experiments on explodingwood with high pressure steam, and in1924 he developed a method of using3

Fig. 2: William Mason examining the Masonite press, c. 1939steam as a propellant to shoot woodchips out of a small muzzle-loadedcannon. Unlike methods that cookedor ground the chips, Mason’s processpreserved the fiber structure of thewood without the loss of cellulosic lignin,the natural bond that holds the fiberstogether.Mason thought the fiber could bepressed into paper or insulation board,and he was able to convince the Wausauinvestors to pay for the construction ofa small insulation board plant and forfurther research. A fortuitous accidentoccurred during one of his experimentswhen he left for lunch and forgot to4release a press that happened to havea leaky valve. This caused heat andpressure to be applied for an unusuallylong period of time, and upon his return,Mason found that the fibers had beenpressed into a thin, dense, hard sheet.The initial plans for the insulation boardfactory were expanded to include themanufacture of this hardboard product.The Mason Fibre Company was formedin 1925, and production began in1926. The name of the company waschanged to Masonite Corporation in1929, and was based in Chicago withproduct development at its Laurel plant(figs. 2 and 3). At first, the operations

utilized only wood waste, but with thecompany’s growth it became necessaryto augment the refuse with woodspecifically cut for operations. Longleafpine and southern gum were primarilyused, but spruce and other hardwoodscould be employed, as well; Robert M.Boehm, Masonite’s Director of Research,stated in 1930, “As yet we have foundpractically no species of wood whichis not suitable for the manufacture ofMasonite products.”2Throughout the company’s earlyyears, a variety of products wereintroduced, including Masonite RoofInsulation, Masonite Insulating Lathe,Masonite QuartRBoard (a wall board),Masonite Cushioned Flooring, MasonitePresdwood, Masonite TemperedPresdwood, and Masonite Temprtile(Tempered Presdwood with score linesto produce the effect of tile). Presdwoodwas a hardboard that was smoothon one surface and textured on theback due the use of a screen used inthe manufacturing process. TemperedPresdwood was made by treatingstandard Presdwood with oil and bakingit at high temperatures, which increasedFig. 3: Masonite Corporation, Laurel, MS, c. 19405

its strength and impermeability. Bothproducts could be finished with paint,stain, lacquer, and varnish.In 1928, the insulation boardmanufacturer Celotex Company beganto produce hardboard similar toMasonite’s. In the litigation that followed,Masonite successfully defended itspatents, and in the early 1930s thecompany entered into contracts withseveral companies that allowed them tosell Masonite products as “agents” undertheir own labels at uniform prices set byMasonite. In 1940, the Anti-Trust Divisionof the U.S. Justice Department claimedthat these agreements violated antitrust laws, and in 1942, the U.S. SupremeFig. 4: “Where will this grainless wood be used next?”, advertisement in Scientific American,June 1928, p. 549.6Court ruled in the government’s favor. Asthe price-fixing clause was the only partof the agreements that was consideredan infringement, the companies signedsimilar contracts without requiring setprices. Masonite eventually cancelledthese agreements in the early 1960sbecause the patents had expired andthe company was beginning to focusproduction on pre-finished productssuch as pegboard, siding, and doors.By the late 1960s, most of Masonite’shardboard was not being sold incommodity form, and by the mid-1970ssales were minimal. Today, there are afew hardboard manufacturers in theUnited States and abroad, includingAmpersand Art Supply in Buda, Texas.Due to the fact that Masonite inventedthe hardboard process and virtuallyheld a monopoly for decades, the term“Masonite” has become a proprietaryeponym, which is a general word thatwas originally a proprietary brand name.Conservator Alexander W. Katlan statedin 1994 that, “All hardboards today arebasically Masonite-process boards.”3In the early years, Masonite sold moreboard insulation than hardboard becausethe latter was a new product, and itsproperties and applications were notwidely known. However, a myriad ofuses were quickly found for Presdwood.A Masonite ad in Scientific Americanof June of 1928 says, “We don’t knowourselves where this grainless woodwill be used next: nobody does. Itsworkability and adaptability are trulyastounding Week after week we hear ofnew uses!” (fig. 4)

Fig. 5: “Masonite Flooring used in Warner Bros.’ ‘Juarez’ featuring Bette Davis, Donald Crisp, and Brian Aherne,” from Frank. C. Lesniak, “Masonite; Takes a Tree Apart Fiber by Fiber and Puts itBack Together in a More Usable Form,” Baldwin-Southwark, 4th qtr., 1939, p. 8. LRMA Archives.Masonite stated that Presdwood couldbe used “as wall and ceiling paneling,exterior walls or roofs in certain typesof construction, truck bodies, buildingforms for concrete constructions, forsigns and billboards, display casesand cutout or panel display in stores,in millwork products, and in manymanufacturing industries such asfurniture, toys, shipping containers,radio cabinets, and many others.”4In 1930, Richard Boehm remarkedthat, “When you look at some ‘milliondollar set’ from Hollywood, whether itdepicts a ballroom scene, a palace, oran exterior, the chances are great thatyou are looking at Presdwood.” (fig. 5)Tempered Presdwood could be usedin the same places as Presdwood, butwas recommended for uses where morestrength and moisture resistance wereneeded, such as dies for automobile andairplane parts and concrete form boards.The remarkable versatility of Masonite’sproducts was revealed at the Century ofProgress International Exposition, heldin Chicago from 1933 to 1934, where vastamounts were used for various functions.As Lisa D. Schrenk observes:Over 300,000 feet of TemperedPresdwood flooring covered theplywood subfloors in the Hall ofScience and the Electrical Building.Builders also used regular Presdwoodin the interiors of many of thepavilions, including the readingroom in the Time and Fortune7

Building, and in the Schlitz Gardenand Mueller Pabst restaurants. Theentire bridge of the Swift Bridgeand Open Air Theatre was built ofMasonite panels, as were all theticket booths, more than 100 OrangeCrush and Citrus Fruits stands, andnumerous individual display booths.Masonite was also used for the soundchamber of forty-five loudspeakersand for every official sign. Engineersspecified two and one half miles ofTempered Presdwood for structuralpanels lining the shore of LakeMichigan and for the fountain at thecenter of the lagoon.5Fig. 6: Masonite: A Souvenir of the 1934 World’s Fair, 1934 booklet, cover. From the collectionof Jablonski Building Conservation.8The company also demonstrated theirproducts’ utility in its Masonite House(fig. 6). Designed by the Chicagoarchitects Frazier and Raftery, thedwelling included a front hall, livingroom, kitchen, bathroom, study, andbedroom, all built with Masoniteproducts. This modern and forwardlooking home was one of the mostpopular features of the fair.A 1935 Masonite publication describes indetail how, room by room, a home couldbe made “finer, more modern, morebeautiful, if you wisely decide to makeuse of Masonite products in it.”6 Forexample, in the kitchen (fig. 7), the lowercabinet is topped by Masonite TemperedPresdwood that functions as a workFig. 7: from Masonite Insulation.Presdwood.Quartboard.Lath.Tempered Presdwood.Temprtile.Cushioned Flooring booklet, 1935, p. 8. LRMA Archives.

surface and a drainboard. The materialis also used for the panels and shelvesof the china cabinets, the panels of thecupboard, and the ceiling. The authorof Masonite’s The ABC of SuccessfulBuilding & Remodeling remarks that,“Science can contribute new buildingmaterials. The architect .who combinesthe skills of engineer and artist candevise perfect plans. Yet the final qualityof every building rests with the skill ofthe men who build it.”7Masonite’s hardboard became animportant and heavily used materialduring World War II as a substitute formetals in a variety of applications, thusvirtually taking it off the non-militarymarket. Moreover, the Army and Navyused large quantities to constructhousing in the form of Quonset hutsthroughout the European and Pacificwar theatres theatres (fig. 8). As a result,Fig. 8: “Shelter Made of Masonite,” from Leader-Call, Laurel, Mississippi, Tuesday, February2, year unknown. LRMA Archives.Masonite Corporation was given threeArmy-Navy Production Awards. Othercompanies used Masonite hardboardin their contributions to the war effort.The Chicago firm of W.L. Stensgaardwas involved in the defense furnishingsmarket, and Henry P. Glass designed“a group of low-cost defense housingfurniture, made of nonessential materials,namely plywood and bent Masonite.”8Due to this military work, Glass hadaccess to Masonite when other designersdid not because of war shortages. Hetook advantage of his experience withthe material after the war, using Masonitehardboard in both institutional anddomestic furniture, notably in his awardwinning 1951 line of “Swingline” children’sfurniture for the Fleetwood FurnitureCompany of Grand Haven, Michigan (fig. 9).Fig. 9: Henry Peter Glass (Austrian/American, 1911-2003) for Fleetwood FurnitureCorporation, Grand Haven, Michigan, Swing-Line Child’s Wardrobe, 1952, painted Masoniteand wood, Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Henry P. Glass, 2000.1339

Fig. 10: Charles Eames (American, 1907-1978) and Ray Kaiser Eames (American, 19121988) for Herman Miller Furniture Company, Zeeland, Michigan, Eames Storage Unit (ESU),designed 1949-50, birch plywood, zinc-plated steel, perforated metal, plastic laminatedplywood, lacquered Masonite, and rubber, St. Louis Art Museum, Friends Fund, 17:1994.The noted designers Charles and RayEames also used Masonite hardboard intheir postwar, modernist furniture. Forexample, their low-cost Eames StorageUnits, or ESUs, designed for HermanMiller, Inc. of Zeeland, Michigan,had interchangeable parts that wereconstructed of wood and steel, andbrightly colored Masonite fronts added atouch of whimsy (fig. 10).Not only did architects and furnituredesigners find uses for Masonite’shardboard. Presdwood was commonlyand widely used by painters from soonafter it was invented and throughoutthe rest of the 20th century. In the1928 advertisement mentioned above,Masonite states that Presdwood was “indaily service at the Chicago Art Instituteas artist’s boards.” However, this early10reference is the only example that thisauthor has found in which the companyitself mentions the material’s use by fineartists. Nevertheless, the hardboard waswell suited for use as a painting support.Throughout the centuries, artists haveused a variety of painting supports,including walls, wood panels, stretchedcanvas, glass, and paper. Before canvascame into general use at the end of the16th century, wood panels were mostoften used for mid-sized paintingsproduced on an easel. The woodensupports were durable and could beeasily sourced from locally found timber.Even after canvas was regularly usedafter the 16th century, wood panelswere still valued because they couldprovide a smooth, texture-less surface.A big drawback to wood panels are theirtendency to warp, shrink, expand, split,and becoming infested with insects.For artistic purposes, Masonite’shardboard was an improvement overwood panels as a rigid support for oiland tempera painting. It was availablein large sheets and was easily sawn;it was inexpensive in comparison toother support material; it had no grainor knots and would not crack or split; itwas resistant to moisture and was notas sensitive to changes in temperatureand humidity; and if correctly prepared,it did not warp. It was also readilyobtainable; in a souvenir brochure forthe 1934 Century of Progress, Masoniteclaims that, “Genuine Masonite productsare sold by nearly 10,000 retail lumberdealers throughout the country.”Although Masonite does not seemto have promoted their hardboard toartists, art experts gave them technicaladvice about how to use it. As examples,

we will look at the writings of threeauthorities: Ralph Mayer, Frederic Taubes,and Reed Kay.9 They are unanimous intheir estimation of Masonite StandardPresdwood as an excellent choice fora rigid support, with Mayer calling ita “superior brand” of hardboard10 andTaubes remarking that “it is more reliableas a support for paintings than any panelmade of wood.”11 There is consensus thatPreswood was the best Masonite productto use, and that the Standard was moresuitable than the Tempered version,as the surface treatment that gave thelatter more strength also preventedoptimal adhesion of priming coats. Theyrecommended using the 1/8” thick type,as thicker versions were too heavy tobe handled easily. Taubes does mentionthat thicker varieties could be used forsmall paintings up to 12” x 16”.12 Theexperts agree that because large panelstended to bend and curved under theirown weight, they needed to be bracedwith strips of wood attached to the backalong the four edges. What constitutesa large panel varies for these experts,however. Mayer specifies pieces largerthan 24” as large,13 Taubes those over 20”x 24”,14 and Kay defines those over 24” x30” as large.15 Mayer remarks that somepainters reinforced all of their panels,no matter the size,16 and Kay relates thatin order to save time and effort, somepainters only braced the paintings thatthey considered successful, or they left itup to the purchasers of the work to do sowhen it was in their possession.17Authorities on artistic techniquerecommend that before beginning apainting, the Presdwood panels shouldbe roughened up with sand paper,scrubbed with alcohol and ammonia,and then coated with primer or gesso. Ifunbraced, both sides need to be coatedin order to keep the panels from curving.This will also reduce the amount ofacidic vapors that are emitted. Raggededges can be smoothed with a file orsandpaper, and rounding or bevelingthe edges will reduce disintegration ofmaterial and loss of paint at the corners.If one wanted the rigidity of hardboardand the texture of canvas, the lattercould be mounted to Presdwood panelsusing glue. Mayer comments that readymade braced panels that are coated withgesso can be purchased from retailersor made to order.18 After Presdwood wasno longer produced in great quantitiesat Masonite’s plants in the United States,for a time it was still being producedabroad,19 and in 1981, Mayer relates thatit was being imported from England andsold by an art supply store, Arthur Brownand Brother in New York.20Numerous American painters usedMasonite’s hardboard productsthroughout the last three quarters of the20th century, employing the material as asupport for paintings in oil (fig. 11), eggFig. 11: Maltby Sykes (American, 1911-1992), Shrimp Boats, 1953, oil on Masonite, TheJohnson Collection, Spartanburg, South Carolina, 2007.05.0311

tempera (fig. 12), acrylic, and polymertempera (fig. 13), among other media.21Early modernist artists such as JohnStorrs (fig. 14) were among the first toutilize the material. Reginald Marsh wentagainst normal practice by paintingon the screen side of Presdwood toproduce his gritty East River (fig. 15).Taubes remarked the rough side is“unsuitable for painting because of itsugly texture,”22 but the ugliness seemsto have suited this Ashcan painter’sobjectives. Artists working for theWorks Progress Administration (WPA)during the Depression, including PedroFig. 12: William C. Baggett, Jr. (American, born 1946), Cage, 1991, egg tempera on Masonite,Collection of the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art, Gift of Hallie and C.G. Hull, 98.28Fig. 13: Karle Zerbe (German/American, 1903-1972), Kiosk I, 1951, polymer tempera onMasonite, Collection of the Columbus Museum, Georgia, Gift of Estelle and Martin Karlin,G.2011.57.112Fig. 14: John Storrs (American, 1885-1956), Nebulous, 1933, oil on Masonite, Courtesy ofKraushaar Galleries

Fig. 15: Reginald Marsh (American, 1898-1954), East River, 1952, oil on Masonite, a LaurenRogers Museum of Art Purchase, 98.2Cervántez (fig. 16), were encouraged towork in less expensive materials, andMasonite’s Presdwood fit the bill. In 1939,Masonite Corporation answered a letterfrom American Regionalist artist JohnSteuart Curry explaining how to attachQuartrboard to a brick wall, perhaps aspart of a mural project.23 To produceworks in his Geometric Abstractionseries Homage to the Square (fig. 17),Josef Albers usually painted on Masoniteboards. He felt that canvas was too

May 03, 2007 · prices. Masonite eventually cancelled these agreements in the early 1960s because the patents had expired and the company was beginning to focus production on pre-finished products such as pegboard, siding, and doors. By the late 1960s, most of Masonite’s hardboard was not being sold in