Transcription

The Byzantine Opus Sectile Floor in the Katholikonof Iveron Monastery on Mount Athos*Dimitrios A. LiakosUDC 726.04:738.5].033(495.631)The Byzantine opus sectile floor in the katholikon ofIveronmonastery is one ofthe best preserved and most remarkableopus sectile floors in Athos, made as a pietre dure like mostAthonite floors. Was constructed around the mid-I I thcentury, probably by craftsmen from the Constantinople,as part ofthe "renovations" commissioned by Georgethe Athonite during his highly creative office as abbotofthe monastery (1045-1056).'H DE 't'ot) EDaqJOVr; eta eir; 'wcov JwpqJar; 1Cai UX11Jla't'cov aA.A.ar; iMar; 't'a'lr; troA. Vjl.6pqJOlr; If/T/qJ{Ul Buxuopeo»eeioa 9avjl.au't't1v 't'lva -rot) 't'exv{'t'ov 't'T,V oooiav xapea't't1ua't'o (The view on the floor of animal forms and otherpatterns formed by tesserae of various shapes attests to thecraftsman's admirable wisdom). It was with these words thatPatriarch Photios described in his 101b Speech of 864 thefloor ofthe church of Our Lady ofthe Pharos, built within theimperial palace of Constantinople between the years864-866.1 This description reflects the impression thatviewers got from the luxurious and richly decorated floor ofan imperial church and gives an overview ofthe subjects andthe quality of contemporary church floor decorations.The floor of Byzantine churches, often referred to intexts as TCa-ror;2 [bottom] or EOOqJor;3 [ground], lends itself tothe development ofa decorative vocabulary with a rich varietyofsubjects (human figures, animal themes, geometrical motifsetc.) in various combinations, while the layout of the compositions accentuates the architectural structure of the church.sOne widespread type of floor decoration in Byzantinetimes is opus sectiles a technique known since the secondcentury BC.6 It involves cutting marble or other materials (e.g.glass) into human and animal shapes and floral or geometricalpatterns and arranging or inlaying them over a background ofdifferent colour to create compositions on wall and floorsurfaces or minor objectsof art.? In Greek bibliography anopus sectile floor is described as jl.apjl.ap09t't'11Jla [marblemarquetry], although the term is limiting in terms of both thematerial and the version of the technique it specifies. sIn Roman and early-Christian times the technique coexisted with mosaic in floor construction.? After the seventhcentury, however, mosaic was used considerably less andopus sectile flourished in floor decoration during the midand late Byzantine periods.tv by contrast, its use in walldecoration was limited. I IA main trait of opus sectile floors from the tenthcentury onwards is a preference for geometrical subjects,particularly circle motifs which can combine with othershapes or form chains, creating various combinations.t?However, some floors are also decorated with other elementssuch as animal themes.n The decorative effect is achievedeither by removing bands from a solid piece of marble andfilling in the gaps between them with small pieces of multicoloured inlays (marquetry) or by laying bands and inlaysdirectly onto a layer of mortar (pietre dure ).14 It is noted thatthese floors flourished greatly in Italy, where they are knownas cosmati, after the name of the famous family of Italianmarble craftsmen who worked on monuments in and aroundRome in the twelfth century.t * I extent my thanks to Dr. loannis Tav1akis, Head of the 10thEphorate of Byzantine Antiquities, who urged me to take up this subject andto my friend and colleage Vangelis Maladakis for valuable discussions. Also,I extent my thanks to the brotherhood oflveron Monastery, especially to theHoly Abbot father Nathanael and the secretary father Christophoros, for theirhospitality and valuable help in my research and photographing of thefloor.1 V. Laourdas, rbwr{ov 0JLu{at, Thessaloniki 1959 (EUT\vtlCeX,IIapeXp'tT\l1a 12), 102. V. also V. Kydonopoulos, llapaTT/P7/ rEU; (JTT/VTaVTlGT/ TOV vaov TT/ eEOT6ICOV TT/ JOfI OJLtMa TOV aTpuxpxoVTO va6 T eEOT6ICOV TOV rbapov. N ia (JTotXela v ip aVn1 TT/ TaVTl , Byzantina 23 (2002-2003) 143-153.rbwr{ovJLE2 For the term in the description by Constantine Rhodios (tenthcentury) of the St. Apostles church in Constantinople (640-676) v. E.Legrand, Description des oeuvres d'art et de l'eglise des Saints Apotres deConstantinople. Poeme en vers iambique, par Constantin le Rhodien, Revuedes etudes grecques 9 (1896) 56.3 The term appears in Procopius's description of the church of StJohn Theologos in Ephesus (llEp{ ICn(JJLaTwv). C Procopii Caesariensisopera omnia IV, ed. J. Haury, G. Wirth, Leipzig 1964 2 , V, a', 64 St, Pelekanidis, IVVTarJLa TWV aA.aWXPt(JnavtlCcOv lfITIqJtOOrrcOv Ban &Jv TT/ BA.A. I, NT/GlwrtlC7] BA. , Vyzantina Mnemeia 1(1988) 13.5 Cf. the exhaustive study by P. Assimakopou1ou-Atzaka, H TEXVtIC7/ opus sectile (J'rT/V EVTO{Xta 8taIC6(JJLT/GT/. IvJLI3oA.7] (JTT/ JLEA.iTT/ TT/ TExvtlC7] a 6 TOV 1 JLiXPt TOV 9 u. X. atcOva JLE f3>/ ta JL vnuela xca talCelJLEVa, Vyzantina Mnemeia 6 (1980).6 Assimakopoulou-Atzaka, Opus seetile, 49.7 On the definition and the variations ofthe technique v. ibid., 3, 4.8 Assimakopoulou-Atzaka, Opus seetile, 18.9 On early Christian mosaic floors v. Pelekanidis, IVVTarJLa, passim; P. Assimakopoulou-Atzaka, IVVTarJLa TWV aA.aWXPt(JnavtlCcOvlfIT/fPtOOrrcOv 8atri8wv TT/ BA.A.&.8 , II, llEA.O 6vvT/Go -ITEpEaBA.A.aBa,Vyzantina Mnemeia 7 (1987).10 N. Nikonanos, Bv{avnvo{ vaoi T eE(J(JaA.{a a 6 TOV 10 atcOva T11V lCaTalCTT/GT/ TT/ 1rEpWX7/t; a 6 TOV TovplCo TO 1393.IvJLf30A.7] (JTT/ !3v'avnv7] apXtTEICTOVtlC7/, Athens 1997, 113, with bibliography.11 Assimakopoulou-Atzaka, Opus seetile, 151, with bibliography.12Ibid., 152.13 V.for example the sections from the floor ofthe three-nave churchat Kokkino Nero, Kissavos, with champleve animal themes combined withopus sectile (Nikonanos, Bv{avnvo{ vaol T11 eE(J(JaA.{a , Ill, tab. 53).14 Assimakopoulou-Atzaka, Opus sectile, 152.15 Ibid., 152, 153. For the cosmati floors v., also, D. F. Glass, Studieson Cosmatesque Pavements, Oxford 1980 (BAR International Series, 82);A. G. Guidobaldi, Tradizione locale e injluenze bizantine nei pavimenticosmateschi, Bollettino d' Arte 69 (1986) 57-72.16 Assimakopoulou-Atzaka, Opus sectile, 157-161.37

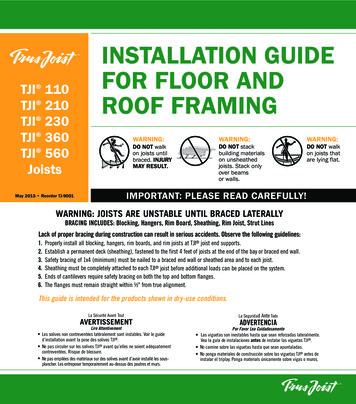

Fig. 2. Stavroniketa Monastery. Katholikon.General view ofthe floor in the naveFig. 1. Iveron Monastery. Katholikon.The opus sectile floor in the naveThere are some particularly illuminating references inwritten sources on floors of the period from the eighth to themid-tenth century, of which few specimens have survived,whereas the references about floor decorations in the centuries after that (eleventh-fourteenth century) are more sporadic.te This information complements the picture we havefrom surviving floors in various regions inside and outsidethe empire, dating from the tenth century onward. The mostimportant examples include the floors of Desiatynna churchin Kiev (ca. 996),17 the katholikon ofIkossifmissa monasteryon Mount Pangeon (ca. 1000),18 Panaghia in Osios Loukas,Fokis (after 1033),19the katholikon ofthe Nea Mom on Chios(1043-1056),20 St John the Baptist in Stoudiou monastery(after 1059),21 the Assumption Church in Nicaea (eleventhC. Mango, Byzantine Architecture, New York 1974, 324; O. Z.Pevny, Kievan Rus, in: The Glory of Byzantium. Art and Culture of theMiddle Byzantine Era A.D. 843-1261, ed. H. C. Evans, W. D. Wixon, NewYork 1997, 288, N2 193 (R. Ousterhout).18 M. Kambouri, Nea CJ'rOlxe{a am) 'f1'/ JlEa0f3 avnvt7 quXC1T/ 'fOV/Ca60A,lIcov 'fT/ jlOVt7 El/Cocntpolv{a , E1tta1:11I10Vt1C E1tE't11P{ ; 't11 ;ITOA t 'tEX,VtlC ; EX,OA ; 'tot AptO''tO'tEAEtot ITUVE1ttO''tftlttot 8EO'O'ul.oV{lC11 ; 5 (1971) 138 sqq., ill. 2, 3.19 P. Mylonas, IIapan1JJ11aEl ato /Ca60A,1/C6 XEA,aVoap{ov. H01ajl6ptpwC1T/ 'fOV vaovA6wvlIcov 'fV11'0V oe XOPO xa: A,l'ft7 trto }\rlOV'Op , Ap:x,utoA.oy(u 14 (1985) 71 and n. 42.20 A. Orlandos, Monuments byzantins de Chios I, Athens 1930, tab.21; Ch. Bouras, H Nea Movt7 xts« Lotopia xca. apXl'fE/C'fOV1/Ct7,Athens 1981,51; A. Missailidou, A. Kavvadia-Spondyli, IIapa'fT/Pt7aEl sea aVCJXEnajlO{ mOlxefwv eto /Ca60A,1/C6 'fT/ Ne Movt7 X{ov,Byzantina 25 (2005) fig. 1.21 A. H. Megaw, Notes on Recent Work ofthe Byzantine Institute inIstanbul, DOP 17 (1963) 339.22 O. Wulff, Die Koimesiskirche in Niciia und ihre Mosaiken nebstden verwandten kirchlichen Baudenkmdlem, Strasbourg 1903, 157-164,tab. VI, X, XI; Th. Schmit, Die Koimesis-Kirche von Nikaia, Berlin 1927,14 sqq., tab. III, IV, X, XI; Mylonas, IIapa'fT/Pt7aEl ato m60A,1/C6XEA,avl5ap{ov, 71 and n. 46.23 P. Miljkovic-Pepek, Veljusa, Skopje 1981, 141, ill. 25; Mylonas,op. cit., 71 and n. 48.24 A. Underwood, Notes on the Work ofthe Byzantine Institute inIstanbul, DOP 9/10 (1956) 299-300, ill. 115-116; Megaw, Notes, 335-340;Th. F. Mathews, The Byzantine Churches ofIstanbul. A Photographic Survey, University Park - London 1976, 88, ill. 10-25; Ph. Schweinfurth, DerMosaikfussboden der komnenischen Pantokratorkirche in Istanbul, Archii1738century),22 the church of Veljusa near Strumica (1080),23 thesouthern church of Pantokrator monastery in Constantinople(first half of the twelfth century),24 the three-nave church ofKokkino Nero, Kissavos (second half of the twelfth celltury),25 the Taxiarchis of Messaria, Andros (1158),26 thechurch of Zoodochos Pigi at Samari, Messenia (thirteenthcentury),27 St Sophia of Nicaea (first half of the thirteenthcentury),28 St Sophia at Trebizond (thirteenth century),29 thechurch of Pantanassa in Philippias, Epirus (thirteenth century),30 the katholikon of Mega Spelaion, Peloponnesus (thirteenth century)31 and others. Floors from mid-Byzantine timescan be found in the katholikon of Osios Meletios monasteryon Mt Kithairon, the Peribleptos church ofPolitika in Euboea,the katholikon of Lechova, the Vlacherna of Arta, the Sagmata monastery, Panaghia ofKrina, Chios, the katholikon ofMonte Cassino monastery etc.32Added to the above indicative list are the opus sectilefloors from mid-Byzantine times that survive in severalAthonite churches.n the katholika of the monasteries ofologischer Anzeiger 1954, 253-260; Ch. Bourns, B avnve "AvarEVVt7aEl " xca 1'/ apXl'fE/C'fOV1/Ct7 'fOV l/ov xai /2 v a1COvo , EA'tiov 't11 ;XptO''ttUvtlC ; Ap:x,UtoAoyt ; E'tutpe{u ; 5 (1966/1969) 259.25 Nikonanos, B avnvo{ vaol 'f1'/ eEaaaJl{a , 111-114.26 A. Orlandos, Bv(aV'flva jl vnueia 'f1'/ }\ vopov, ApX,E{OV 'tWV t UV'ttVcOV f.l.V11IJ.E{WV 't11 ; EAMXOO ; 8 (1955-1956) 17, ill. 8.27 C. von Scheven-Christians, Die Kirche der Zoodochos Pege dieSamari in Messenien (doctoral thesis), Wuppertall982, tab. 35-38.28 Ch. Pinatsi, The pavement of Hagia Sophia in Nicaea, BZ 99/1(2006) 119-126, pI. XIII-XVIII. For another opinion on the pavement'sdating in eleventh century v. S. Eyice, Two Mosaic Pavements from Bithynia, DOP 17 (1963) 373-374, ill. I, tab. 2-10.29 S. Balance, The Byzantine churches ofTrebizond, Anatolian Studies 10 (1960) 161-162; The Church ofHagia Sophia at Trebizond, ed. D.Talbot-Rice, Edinburg 1968,83-87.30 G. Vokotopoulos, Ilavtavaaaa lA,l11'maO , Athens 2007,30-37.31 Ch. Chotzakoglou, Ein spatbyzantinisches Opus-Sectile-Paviment aus der Klosterkirche von Mega Spelaion, Peloponnes. Technik,Thematik und Symbolik, in: Wiener Byzantinistik und Neograzistik. Beitrage zum Symposion vierzig Jahre Institut fiir Byzantinistik und Neogriizistikder Universitiit Wien im Gedenken an Herbert Hunger (Wien, 4.-7. Dezember 2002), Wien 2004, 99-131.32 Kambouri, Nea eJ'f01xe{a, 141-143.33 Generally for the opus sectile floors in Athonite monasteries v. P.Mylonas, A6wvl/Ca &X11'El5a varov xca 1'/ avJlf3oA,t7 'fOV eJ'f1'/ XPOVOA,6rT/C1T/'fWV jl V1]jlefwv, in: 'Orooo aVjl11'6c]10 pv(avn Vt7 xca jlE'fa{3v(avn Vt7 apxalOA,Or{a xca 'fexv1'/ . ITp6yPUf.l.I1U lCut1tEptA 'I'Et ; EtO'11'Y aEWV !CUtUVUlCOtvcOO'EWV (A91lvu 13, 14 !CUt 15 Mmou 1988), Athens 1988,71-72.

Vatopedi (late tenth - early eleventh century),34 Great Lavra(1020-1060),35 Chilandar (eleventh century),36 Xenophontos (eleventh century),37 Karakallou (eleventh century),38Iveron (mid-eleventh century), which we are discussing here(Fig. 1),39 the main church of the Vatopedian Skete ofAghios Demetrios (eleventh century),40 the chapel of St.Anargyroi in monastery of Vatopedi (eleventh century)41and the church ofthe Chilandarean small monastery ofAgiosVassilios (eleventh century).42 In these list we could add theparts of the opus seetile floor that survive in the katholikonfrom Zygou monastery, today out of the Mt Athos territory(eleventh cenruty).43 Moreover, segments of an opus seetilefloor from the late tenth or early eleventh century were foundin the Monastery of Agiou Pavlou, possibly remnants of thefloor ofthe monastery's first katholikon.w The floors in mostAthonite churches follow the pietre dure version of opusseetile, while the marquetry technique is found in the surviving part of the floor of the Monastery of Agiou Pavlou.ssTheir decoration generally consists of compositions of geometrical motifs based on rectangular and circular shapes;Prof. Mylonas rightly described this as the 'classic' way, incontrast with the Comnenian decorativeness of twelfth century floors as typifted by that of the southern church ofPantokrator monastery in Constantinople.46Attempting a brief overview of the development offorms and decorations on Athonite floors in post-Byzantinetimes, and given the erratic representation of examples fromall periods, we note the floor in the katholikon of Stavroniketa monastery, which must have been constructed between 1540-1545 as part ofthe refurbishment work commissioned by Patriarch Ieremias 1.47 The incisions made in thecentral section form a simple geometrical decoration on themarble surface (a broad stylised rodax surrounded by alternating zones of radial and square motifs, a zone oftriangulardecorations, etc.) and are ftlled with marble inlays or lead(Fig. 2). This decoration ofIslamic inspiration forms

the Athoniteduringhis highlycreative office as abbot ofthe monastery(1045-1056). 'H DE 't'ot) EDaqJOVr; etaeir;'wcovJwpqJar; 1Cai UX11Jla 't'cov aA.A.ar; iMar; 't'a'lr; troA.Vjl.6pqJOlr; If/T/qJ{Ul Buxuopeo» eeioa 9avjl.au't't1v 't'lva-rot) 't'exv{'t'ov't'T,V oooiav xapea 't't1ua't'o(The view on the floor ofanimalforms and other patternsformed by tesserae ofvarious shapes attests to the .