Transcription

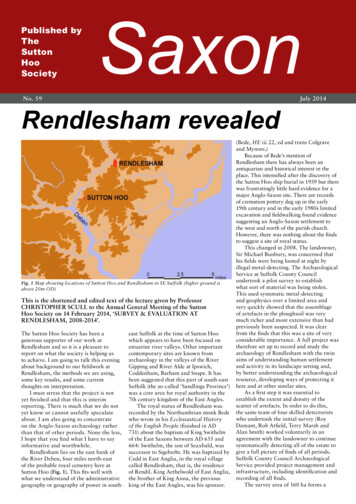

Published byTheSuttonHooSocietyNo. 59SaxonJuly 2014Rendlesham revealedFig. 1 Map showing locations of Sutton Hoo and Rendlesham in SE Suffolk (higher ground isabove 20m OD)This is the shortened and edited text of the lecture given by ProfessorCHRISTOPHER SCULL to the Annual General Meeting of the SuttonHoo Society on 14 February 2014, ‘SURVEY & EVALUATION ATRENDLESHAM, 2008-2014’.The Sutton Hoo Society has been agenerous supporter of our work atRendlesham and so it is a pleasure toreport on what the society is helping usto achieve. I am going to talk this eveningabout background to our fieldwork atRendlesham, the methods we are using,some key results, and some currentthoughts on interpretation.I must stress that the project is notyet finished and that this is interimreporting. There is much that we do notyet know or cannot usefully speculateabout. I am also going to concentrateon the Anglo-Saxon archaeology ratherthan that of other periods. None the less,I hope that you find what I have to sayinformative and worthwhile.Rendlesham lies on the east bank ofthe River Deben, four miles north-eastof the probable royal cemetery here atSutton Hoo (Fig. 1). This fits well withwhat we understand of the administrativegeography or geography of power in south-east Suffolk at the time of Sutton Hoowhich appears to have been focused onestuarine river valleys. Other importantcontemporary sites are known fromarchaeology in the valleys of the RiverGipping and River Alde at Ipswich,Coddenham, Barham and Snape. It hasbeen suggested that this part of south-eastSuffolk (the so-called ‘Sandlings Province’)was a core area for royal authority in the7th century kingdom of the East Angles.The royal status of Rendlesham wasrecorded by the Northumbrian monk Bedewho wrote in his Ecclesiastical Historyof the English People (finished in AD731) about the baptism of King Swithelmof the East Saxons between AD 655 and664: Swithelm, the son of Seaxbald, wassuccessor to Sigeberht. He was baptized byCedd in East Anglia, in the royal villagecalled Rendlesham, that is, the residenceof Rendil. King Aethelwold of East Anglia,the brother of King Anna, the previousking of the East Angles, was his sponsor.(Bede, HE iii 22, ed and trans Colgraveand Mynors.)Because of Bede’s mention ofRendlesham there has always been anantiquarian and historical interest in theplace. This intensified after the discovery ofthe Sutton Hoo ship burial in 1939 but therewas frustratingly little hard evidence for amajor Anglo-Saxon site. There are recordsof cremation pottery dug up in the early19th century and in the early 1980s limitedexcavation and fieldwalking found evidencesuggesting an Anglo-Saxon settlement tothe west and north of the parish church.However, there was nothing about the findsto suggest a site of royal status.This changed in 2008. The landowner,Sir Michael Bunbury, was concerned thathis fields were being looted at night byillegal metal-detecting. The ArchaeologicalService at Suffolk County Councilundertook a pilot survey to establishwhat sort of material was being stolen.This used systematic metal-detectingand geophysics over a limited area andvery quickly showed that the assemblageof artefacts in the ploughsoil was verymuch richer and more extensive than hadpreviously been suspected. It was clearfrom the finds that this was a site of veryconsiderable importance. A full project wastherefore set up to record and study thearchaeology of Rendlesham with the twinaims of understanding human settlementand activity in its landscape setting and,by better understanding the archaeologicalresource, developing ways of protecting ithere and at other similar sites.As a first step it was essential toestablish the extent and density of thescatter of artefacts. In order to do this,the same team of four skilled detectoristswho undertook the initial survey (RoyDamant, Rob Atfield, Terry Marsh andAlan Smith) worked voluntarily in anagreement with the landowner to continuesystematically detecting all of the estate togive a full picture of finds of all periods.Suffolk County Council ArchaeologicalService provided project management andinfrastructure, including identification andrecording of all finds.The survey area of 160 ha forms a

Fig. 2 Map of the survey area (outlined in black) with all Anglo-Saxonfinds plotted (red diamonds). (River Deben, floodplain and land over20m coloured.)transect 2.25 km N-S along the eastbank of the River Deben and 1.25 kmE-W across the grain of the landscapefrom valley bottom to interfluve (Fig. 2).This is enough to be sure that patterns ofconcentration, presence and absence ofarchaeological material are genuine, andto examine how past activity changedwith terrain.The metal-detector survey recoveredmaterial from the ploughsoil or topsoilwhich had either been dropped there orploughed-up from buried archaeologicalfeatures. The detectorists also lookedfor non-metal finds such as pottery andworked flint. The precise location ofevery find is recorded using a hand-heldGPS device. All finds are then passed toSuffolk County Council for identification,cataloguing and visual recording. Allfinds information is held on an MS Accessdatabase and this is integrated with othersurvey data in a project GIS for ease ofhandling and analysis. For example, thedensity and distributions of different findtypes can easily be mapped.As well as the metal-detecting, theproject has also undertaken furthergeophysical survey which shows that theconcentration of metal-detector findscoincides with a spread of archaeologicalfeatures. Trial excavations in the autumnof 2013 confirmed that some of these areAnglo-Saxon Grubenhäuser and othersettlement features (Fig. 3).To date 3,493 finds have beenrecorded, representing activity fromprehistory to the 21st century. Althoughthere are shifts in the concentrations ofmaterial over time, the overall patternpoints to Rendlesham as a favouredlocation for settlement and farming from2Fig. 3 Anglo-Saxon Grubenhaus under excavation in October 2013.the late Iron Age if not earlier, with findsclustering on the more fertile soils between10m and 30m OD. Magnetometryover 46 ha, where the concentration offinds is most dense, confirms a complexpalimpsest of archaeological features fromthe Bronze Age to post-Medieval.The proportion of Anglo-Saxon findsis unusually high, indicating a rich andimportant settlement. There is evidence forAnglo-Saxon activity from the 5th to 11thcenturies but the majority of finds belongto the period of the 6th to 8th centuries.The evidence of finds and magnetometrysuggests that the settlement at this timespread over an area of up to 50 ha,although within this there were differentconcentrations of settlement and activityareas (Fig. 2). We have evidence from bothmetal-detecting and trial-excavations thatthere was at least one cemetery associatedwith the settlement.Skilled metalworkers were makingdress fittings, jewellery and other itemsat Rendlesham in the late 6th and 7thcenturies. The evidence for this comesfrom unfinished items at different stages ofmanufacture, scrap metal, manufacturingwaste and lead models which were usedin making the moulds for casting (Fig.4). Most finds relating to metalworkingwere found in the same area, perhapsindicating the location of one or moreworkshops. Completed items of thesame type as unfinished pieces have beenfound, indicating that some at least of thematerial made at Rendlesham was madefor and used by the people who lived there.Both Continental and Anglo-Saxongold coins and silver pennies have beenfound at Rendlesham. There are alsoweights, which were used to check theweight of gold coins and to weigh bullionfor use as currency (Fig. 5). Coin may havechanged hands in the payment of taxesor fines or as gifts by a lord or king to hisfollowers in reward for services renderedand to secure future loyalty, and this mayexplain much of the earlier gold coinage.The silver coinage is more likely to havebeen used in commercial transactions, andit seems likely that Rendlesham was a sitefor markets or fairs. Foreign traders inexpensive and luxury goods would havebeen attracted to an important settlementwhen the king and his retainers were inresidence and where the important folkof the kingdom might gather for councilsand assemblies.There is other evidence for tradeand exchange at Rendlesham as well asthe coinage. Finds include mounts fromhanging bowls, which were acquired fromnorth and west Britain, and two fragmentsfrom the foot rings of Coptic bowls,acquired from the eastern Mediterranean.Finds of high-quality metalworkindicate that Rendlesham was an éliteresidence. Items such as a gold-and-garnetsword pyramid (Fig. 6) were owned,worn and lost by members of the highestaristocracy or the royal kindred. Suchostentatious jewellery in precious materialswas worn as a statement of rank andwealth. We see here evidence of the usein life of the sort of possessions that wereburied with their dead owners at SuttonHoo. This social élite was supported bya large population of slaves and servants,farmers, craft specialists, administratorsand retainers. The diversity of skills, rolesand social positions among this permanentpopulation at Rendlesham is reflected inthe range of personal items. Simple pinsSaxon 59

Fig. 4 Evidence for metalworking: unfinishedcopper-alloy Anglo-Saxon pin and bucklewith finished examples of each and a piece ofbronze-working debris.Fig. 5 Gold and silver coins and two copper-alloy weights.and buckles made of copper-alloy are theeveryday equivalents of the jewellery wornby aristocrats.There is thus clear evidence for socialand economic centrality at Rendleshamand even without Bede’s reference tothe vicus regius (royal settlement) thearchaeology would suggest that this wasan important centre.We therefore interpret the site as aresidence, and a farm, and a tribute centrewhere the land’s wealth was collectedand re-directed, major administrativepayments made, and important social andpolitical events were transacted. It was atthe apex of a system of surplus extractionand jurisdiction, and at the centre of thesystems of consumption, redistributionand patronage that fuelled élite social andpolitical relationships.Kings divided their time betweendifferent establishments and so Rendleshamwas probably a permanent centre foragrarian or economic administrationbut periodically hosted other functions(military assemblies, the transaction ofjustice, markets or fairs) as and when theKing was in residence. The broader scatterof metalwork finds includes items suchas harness and weapon fittings consistentwith a high-status social milieu whichmight well be explained as the aggregateloss from years of periodic gatherings inthe paddocks around a royal residence.We should perhaps envisage a tent villagewith the permanent population augmentedwhen the King and his household were inresidence and swelling further when therewere assemblies or fairs.It has been suggested that Anglo-Saxonroyal or high-status sites were short-livedelements of a shifting landscape but that wasnot so here: Rendlesham remained a centralplace for at least 300 years. It is thoughtthat there were major re-organisationsof the landscape in the later 6th and 7thcenturies, with smaller landholdingsconsolidated into complex estate structureas royal and lordly power increased. Ifso, then Rendlesham was a fixed elementaround which such changes occurred. Thisin turn argues for a greater continuity andstability of administrative arrangementsand local power structures than hassometimes been envisaged for this period.Rendlesham is one of the handfulof high-status sites of the Early andMiddle Anglo-Saxon periods which canbe securely identified in contemporarydocumentary sources, and is the only oneof this small group for which there is suchabundant, sensitive and precise materialculture data. Consequently there is highpotential here to establish the culturalsignature of a 7th-century vicus regiuswww.suttonhoo.organd to elucidate its spatial organisationand its social and economic character andcontacts. Because its status is documentedthere is also potential to calibrate othersites known primarily from surface finds(ploughzone assemblages or ‘productive’sites) against Rendlesham as a social andeconomic benchmark.Rendlesham is also something newin the archaeology of the Early AngloSaxon Kingdoms: a long-lived centralplace complex. Such sites are known inSweden and Denmark at this time buthave not yet been recognised elsewhere inEngland. The archaeology at Rendleshamtherefore has an international as well as anational importance.Finally, because all periods fromprehistory to modern are represented inthe archaeology at Rendlesham there istremendous potential here to examine howsettlement and activity here changed overtime and within its immediate landscape.AcknowledgementsFig. 6 Gold and garnet sword fitting (width atbase 20.6mm).The Rendlesham Project is funded bySuffolk County Council, The Sutton HooSociety, English Heritage, the Society ofAntiquaries of London, the Suffolk Institutefor Archaeology and History and the RoyalArchaeological Institute. Fieldwork hasbeen undertaken with the kind supportand encouragement of the landowners,Sir Michael and Lady Bunbury, and thefarmer, Philip Westrope. Faye Minter (SCCArchaeological Service) manages findsidentification, recording, cataloguing andanalysis. The project is directed by JudePlouviez (SCC Archaeological Service)and Professor Christopher Scull (CardiffUniversity & University College London).3

Brilliant! Sae Wylfing tobe based in WoodbridgeSae Wylfing, the half-length replica of the Sutton Hoo ship, is now on semi-permanent loan to WoodbridgeRiverside Trust, though it remains in the ownership of the Gifford family. The Riverside Trust is the voluntarycommunity group representing the interests of local people in the redevelopment of the old Whisstocks boatyardon the waterfront in Woodbridge, as described on the front page

Skilled metalworkers were making dress fittings, jewellery and other items at Rendlesham in the late 6th and 7th centuries. The evidence for this comes from unfinished items at different stages of manufacture, scrap metal, manufacturing waste and lead models which were used in making the moulds for casting (Fig. 4). Most finds relating to metalworking