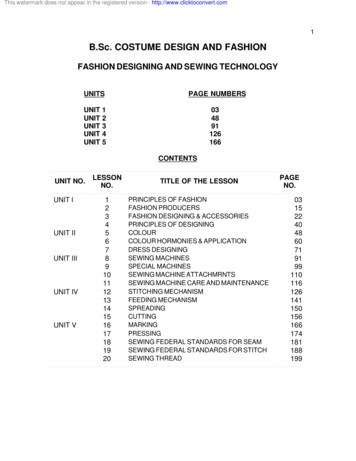

Transcription

A History ofFashion andCostumeElizabethanEnglandKathy Elgin

Elizabethan EnglandLibrary of Congress Cataloging-inPublication DataCopyright 2005 Bailey Publishing Associates LtdProduced for Facts On File byBailey Publishing Associates Ltd11a WoodlandsHove BN3 6TJProject Manager: Roberta BaileyEditor: Alex WoolfText Designer: Simon BorroughArtwork: Dave Burroughs, Peter Dennis,Tony MorrisPicture Research: Glass Onion PicturesConsultant:Tara Maginnis, Ph.D. ,Associate Professor,University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and creator of thewebsite,The Costumer’s Manifesto(http://costumes.org/)Printed and bound in Hong KongAll rights reserved. No part of this book may bereproduced or utilized in any form or by any means,electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,recording, or by any information storage or retrievalsystems, without permission in writing from thepublisher. For information contact:Facts On File, Inc.132 West 31st StreetNew York NY 10001Facts On File books are available at specialdiscounts when purchased in bulk quantities forbusinesses, associations, institutions, or salespromotions. Please call our Special SalesDepartment in New York at 212/967-8800 or800/322-8755.You can find Facts On File on the World WideWeb at: http://www.factsonfile.comElgin, Kathy, 1948–A history of fashion and costume.Elizabethan England/Kathy Elgin.p. cm.Includes bibliographical references andindex.ISBN 0-8160-5946-21. Clothing and dress—England—History—16th century. 2. 34.E54 2005391/.00942/09031—dc 222004060882The publishers would like to thank thefollowing for permission to use theirpictures:Art Archive: 6, 7 (top), 8, 18, 22, 25,30, 31 (top), 36, 39 (top), 41, 48, 53,55, 57Bridgeman Art Library: 7 (bottom), 9,11, 12, 16 (left), 19, 20, 21, 23, 26 (top),27, 32, 34, 35, 39 (bottom), 40, 43(bottom), 44, 54, 58Mary Evans Picture Library: 10, 17, 59Topham: 14, 16 (right), 28 (bottom),29, 31 (bottom), 37, 38, 43 (top), 46, 51Victoria & Albert Museum: 26(bottom), 28 (top)

ContentsIntroduction5Chapter 1: Elizabethan Fashion6Chapter 2: Details and Accessories18Chapter 3: Fashion and Society30Chapter 4: Dressing Up38Chapter 5: Casual Clothing46Chapter 6: Work Clothes and Uniforms50Chapter 7: The Jacobeans58Timeline60Glossary61Further Information62Index64

IntroductionThe reign of Elizabeth I was one of the most dazzling periodsof English history. It was the age of Shakespeare, of WalterRaleigh, and Francis Drake.While at home great advances werebeing made in science, religion, medicine, poetry, and drama,across the seas explorers were mapping a whole new world.Under Elizabeth, England enjoyed a long period of peace andprosperity. People had money to spend on luxuries, and moreof them had time on their hands for leisure pursuits. It was thebeginning of consumer culture, and clothing was the mostobvious way of displaying the newfound wealth. Lavishnessand ostentatious display were the watchwords, not only for thearistocracy at court but also for the rising middle classes, manyof whom had made their recent fortunes trading the verytextiles that were at the heart of the new fashion industry. Inthis mood of national confidence, merchants ventured fartherabroad, trading English wool for silks, jewels, and preciousstones in Venice,Turkey, Russia, and China.Elizabethan costume became more lavish—more consciouslyelaborate—than in any period before or since. It was alsoalmost certainly more uncomfortable, especially for women,who found themselves laced into impossibly tight bodices andimprisoned by huge ruffs around their necks. But men andwomen alike put up with it all for the sake of appearance.Walter Raleigh, though a shrewd and fearless explorer, was alsoa great dandy, only content when in the forefront of fashion.Fortunately for us, the Elizabethan period was also the goldenage of English portrait painting. Everyone who could afford it,from the queen down, dressed in their best clothes and hadthemselves painted for posterity, and it is thanks to thesewonderful paintings that we know so much about the fashionsof the day.We have clues, too, in the many church brasses andmemorials erected to wealthy local benefactors in parishesthroughout the country.There were few, however, who cultivated their own image withmore care and guile than Queen Elizabeth herself, and it wasshe who had the greatest and most lasting influence on fashion.

Chapter 1: Elizabethan FashionThe Legacy of the TudorsThe fashion of the Tudors, in the years immediatelypreceding the Elizabethan period, wascharacterized by a horizontal, rather flattened line. KingHenry VIII, Elizabeth’s father, best shows off the fashionof his day in the many portraits painted of him. Henrylooks out aggressively from these paintings, splendid butsomewhat squat and top-heavy in a broad-shouldered,fur-lined gown with huge sleeves, flat velvet cap, andshoes with squared-off toes.The gown is worn open toreveal an ornate, pleated doublet and, of course, thecodpiece, exaggeratedly large and ornate. It’s anoverwhelming impression of bulk: a solid and powerfulmasculinity offset by the softness of voluminous folds ofrich, fur-lined fabric.men and women might be eitherhigh collared or, more typically, lowand square-cut, with the undershirtor chemise sometimes visible above.Almost every woman wore theangular “gable” headdress.Renaissance CourtMembers of Sir ThomasMore’s family are seen herewearing a mixture of Tudorand Elizabethan styles.6Tudor women’s dress was modest,consisting of a one-piece bodice andskirt, or kirtle, worn under an amplegown which was open at the front toreveal the skirt. Necklines for bothAn astute, highly educated, and“modern” prince, Henry set out tocreate a true Renaissance court inLondon that would outshine thoseof France and Spain.This would beachieved not only through learningand culture but through the displayof visual splendor. Henry encouragedthe importing of fine fabrics—damasks, satins, and brocades—from Europe and obviously tookgreat delight in wearing them

Elizabethan Fashionhimself. From his wardrobe accounts,we know that Henry possessed“doublets of blue and red velvet,lined with cloth of gold,” and one“of purple satin embroidered withgold and silver thread and set aboutwith pearls.” In 1535 he received apurple velvet doublet embroideredwith gold as a gift from ThomasCromwell. Some of Henry’s clotheswere said to be so oversewn withjewels that the original fabric couldhardly be seen.A Passion for FashionThis period also saw the emergenceof “fashion” as a concept. OnceRenaissance thinking had placed manat the center of his own universe,individual personality came to thefore.What one wore came to be seenas a statement of this personality, or,as Shakespeare says in Hamlet, “theapparel oft proclaims the man.”This magnificent timber-framed Tudorfarmhouse is just outside Stratford-uponAvon, where Shakespeare was born.More personal adornment, brightercolors, and fine fabrics were all waysof making this statement.Under Henry’s younger daughterElizabeth, who came to the throne in1558, the English passion for fashionwould reach its highpoint. She lovedfine clothes and jewelry as much asher father, but in her reign theirdisplay was to take a verydifferent direction.The headdress and hoodworn by Jane Seymour, thirdwife of Henry VIII, echo the shapeof the windows in the building above.Dress and ArchitectureFashions in clothing often show fascinating similaritieswith the architecture of the period. The medievalperiod had been characterized by soaring spiresand pointed Gothic arches, shapes which weremirrored in the excessively elongated andpointed sleeves, shoes, and highheaddresses of court wear. In the clothingof the Tudor period which followed, theflattened shapes and straight, horizontallines echo the style of their relativelylow-rise and angular buildings. Inparticular, the gable headdress worn by afashion-conscious Tudor noblewomanexactly resembled the flattened-arch designof the windows of her house.

Fashion and PoliticsEuropean fashion was generallydictated by the country currently inthe political ascendancy. In the earlyyears of the sixteenth century, Franceand Germany held sway and it was totheir fashions for bright colors andextravagantly woven fabrics thatHenry VIII had looked.The Power of SpainAlready, though, Spanish influencehad gained a foothold in Englandthrough two royal marriages—Henry’s to Catherine of Aragon,followed by the brief andunsuccessful union of their daughterMary Tudor with Philip of Spain.From the middle of the century,Spain emerged as the dominantpower in Europe, and from 1556onward it was to the court of PhilipII that all eyes turned.The rigidity of the Spanish courtfound expression in stiff, buttoned-upstyles and dark colors, predominantlyblack, and these became the keynotesThe reserved, brooding personality of Philip IIof Spain set the style for a dark and severecourt dress.of Elizabethan fashion. Curiously,even though political relations withSpain were tense for most ofElizabeth’s reign, the English showedno less enthusiasm for the fashions oftheir enemy.The Elizabethan CourtQueen Elizabeth’s WardrobeAccounts, 1600Strict and detailed accounts were kept of themonarch’s possessions and all expenditure in theroyal household. From these we know that, excludingher coronation and ceremonial robes, Queen Elizabethhad at least: 99 robes; 102 French gowns; 67 roundgowns (pleated all around); 100 loose gowns; 126kirtles; 136 foreparts (embroidered under-petticoats);125 petticoats; 96 cloaks; 91 cloaks and safeguards(over-skirts); 43 safeguards and jupes (jackets); 85doublets; 18 lap mantles; 27 fans; and 9 pantofles(slippers).8However, this was the golden age ofdrama, and enthusiasm for thetheatrical permeated everyday life,subtly undercutting the seriousness ofthe true Spanish style. QueenElizabeth encouraged the portrayal ofherself as an invented character, nevershown realistically but always as anallegorical figure. She was paintedholding a rainbow or a symbolicflower: poets compared her to agoddess or to the moon—anythingbut a real human being. Living outthis fiction herself, Elizabeth

Elizabethan Fashiondemanded that the men and womenattending her should also be playersin the on-going glamorous drama ofcourt life. Artificiality was thewatchword, and the more obviouslyartificial the better.Fashion, for both sexes, went toextremes of design and lavishness,and changed almost by the week.Anyone appearing at court in anunflattering color or last month’sfashion attracted her eagle eye andwas a target for ridicule. Since beingout of the queen’s favor could belife-threatening, her young courtierswere kept in a constant state ofrivalry for her approval, competingwith each other in fashion as muchas in the tilt yard or on the tenniscourt. All this attracted thedisapproval of observers like WilliamHarrison who, in his Description OfEngland (1577), noted that: “Thephantastical folly of our nation (evenfrom the courtier to the carter) issuch that no form of apparel liketh[pleases] us longer than the firstgarment is in the wearing, if itcontinue so long, and be not laidaside to receive some other trinketnewly devised by the fickle-headedtailors, who covet to have severaltricks in cutting, thereby to drawfond customers to more expense ofmoney ”Even when Queen Elizabethand her court were visitinga great country house,everyone dressed in theheight of fashion.9

Womenswear 1550–1580The clothing of upper-class womendid not change radically in the firstdecades of the Elizabethan period,but there were two importantdevelopments: the separation ofbodice and skirt into two distinctgarments, and the gradual discardingof the gown.The skirt still fell in asmooth cone shape from the waist tothe floor, while the bodice—sometimes strangely referred to as “apair of bodies”—was becomingincreasingly tight and constricting.Stiffened with stays made ofwhalebone, or sometimes cane,The Spanish farthingaleand false sleeves hangingfrom the shoulders createthe typical shape of themid-Elizabethan period.wood, or metal, it fitted closely andended in a deep point at the waist,which had to be as slim as possible.According to Catherine de Medici,regent of France and fashiondictator, a thirteen-inch (33-cm)waist was the maximum which couldbe allowed in polite society.The SpanishFarthingaleTo make the waist appear evensmaller and disguise the hips, a newdevice called the farthingale, orverdingale, was developed.This was anunderskirt into which were sewncircular hoops made of whalebone,wire, or wood. Increasing in size fromwaist to ground, they formed a bellshaped cage which made the skirtstand out from the body.This stylewas known as the Spanish farthingale.By the 1570s it was immenselypopular and was worn by women ofall classes. A simpler alternative wasthe “bum roll,” a roll of paddingwhich tied around the waist.As the use of padding made thefemale silhouette more unnatural,clothes became far moreuncomfortable. Given thatElizabethan families tended to belarge and women were thereforepregnant for much of their lives, theconstricting effect of fitted bodice,narrow waist, and tight sleeves mayhave helped to account for the highrate of mother and child mortality.The impulse to display oneself,however, overrode the discomfort.Between 1550 and 1580 the inventive10

Elizabethan FashionLace MakingThe most delicate lace was bobbin lace, developed in Flanders in the 1520s. This is producedby working together threads from several bobbins around pins in a stuffed cushion. The mainfeature of bobbin lace is the triangular edging resembling teeth, which gave it its French name,dentelle (from dent meaning “tooth”). Bobbin lace, although skillful, required no special toolsand was therefore accessible to amateurs. Needle lace, invented by Venetian embroiderersaround 1540, is produced by pulling threads from a base fabric to leave a mesh and then

the true Spanish style.Queen Elizabeth encouraged the portrayal of herself as an invented character,never shown realistically but always as an allegorical figure.She was painted holding a rainbow or a symbolic flower:poets compared her to a goddess or to the moon—anything but a real human being.Living out this fiction herself,Elizabeth Fashion and Politics