Transcription

JOURNAL OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS2018, 51, 502–520NUMBER3 (SUMMER)SHAPING COMPLEX FUNCTIONAL COMMUNICATION RESPONSESMAHSHID GHAEMMAGHAMIWESTERN NEW ENGLAND UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITY OF THE PACIFICGREGORY P. HANLEYWESTERN NEW ENGLAND UNIVERSITYJOSHUA JESSELWESTERN NEW ENGLAND UNIVERSITY AND QUEEN’S COLLEGEROBIN LANDAWESTERN NEW ENGLAND UNIVERSITYResponse efficiency plays an important role in the initial success of functional communicationtraining (FCT). Although low-effort functional communication responses (FCRs) have beenshown to be most effective in replacing problem behavior; more developmentally advancedFCRs are favored later in the treatment process. Attempts to teach these more complex FCRs,however, often lead to the resurgence of problem behavior. In this study, we provide a detaileddescription of an effective shaping process applied within a changing criterion design to developcomplex FCRs from simple FCRs without resurgence of problem behavior. Four children withvarious language and intellectual abilities participated in this study. A practical shaping procedure, suitable for typical teaching contexts, is described for two participants in Experiment1. The necessity and efficacy of the shaping process are demonstrated with the participants inExperiment 2. Implications for practice and research are discussed.Key words: autism, functional communication training, interview-informed synthesizedcontingency analysis, problem behavior, shapingFunctional communication training (FCT) isan efficacious treatment that results in substantialreductions of problem behavior (Durand, &Moskowitz, 2015; Tiger, Hanley, & Bruzek,2008). With FCT, a socially appropriateresponse that serves the same function as problem behavior is taught via prompting and a richschedule of reinforcement to eliminate problembehavior. Horner and Day (1991) demonstratedthat the new functional communication responseWe would like to thank Laura H. Hanratty, and theundergraduate research assistants, Matthew Darcy, TiffanyD. Leno, Ashley McMullen, and Regina Nastri for theirassistance with this project. Correspondence can bedirected to mghaemmaghami@pacific.eduAddress correspondence to Mahshid Ghaemmaghami,Ph.D., BCBA-D, Department of Psychology, Universityof the Pacific, 3601 Pacific Ave., Stockton, CA 95211,Tel: 209-946-7311, Email: mghaemmaghami@pacific.edudoi: 10.1002/jaba.468(FCR) may not occur in lieu of problem behaviorunless this new response is more efficient thanthe problem behavior. According to Horner andDay, response efficiency is affected by theamount of effort required to emit a response andthe schedule and immediacy of reinforcement forthat response. For instance, Horner and Dayfound that a one-word (low-effort) response wasmore effective than a full-sentence (high-effort)response. The importance of the efficiency ofFCRs has been replicated across various modalities (e.g., Buckley & Newchok, 2005; Richman,Wacker, and Winborn, 2001), and the leasteffortful response has been the most effective inevery case. Although these results have led to therecommendation that low-effort responses beidentified and selected as the target FCR(Ringdahl et al., 2009; Tiger et al., 2008), thereis also some evidence suggesting that more 2018 Society for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior502

SHAPING COMPLEX COMMUNICATION RESPONSEScomplex FCRs, such as those that include anautoclitic frame (e.g., “May I have the toy,please”) may lead to better generalization andemergence of novel mands (Hernandez, Hanley,Ingvarsson, & Tiger, 2007). For these reasons,Tiger et al. (2008) recommended that simple,low-effort responses only be used as the initialFCR and more complex FCRs eventuallyshaped.Teaching more complex FCRs that involveobtaining a listener’s attention, making eyecontact, ensuring acknowledgement, and adding an autoclitic frame and a social nicety mayalso be more consistent with the general goal ofaddressing the common social and communicative deficits of children and adults with severeproblem behavior, especially those with autism(Hwang & Hughes, 2000; Macintosh & Dissanayake, 2006). Complex FCRs that aredevelopmentally and socially appropriate couldalso be more acceptable and recognizable topeers and novel adults (Durand & Carr,1992), which may increase the generality,social validity, and overall effectiveness ofFCT. The detrimental effects of responseeffort, however, must be mitigated for thesebenefits to be realized.Despite the recommendations by Tigeret al. (2008), and the potential benefits of morecomplex communication responses, there is alack of clarity on how to mitigate the potentialside effects of increased response effort as veryfew studies of FCT have included a transitionfrom simple FCRs to more complex forms.A two-step approach of moving from a simpleFCR (“My way”) to one of greater complexity(e.g., “Excuse me? [pause] May I have my way,please?”) was briefly described by Hanley, Jin,Vanselow, and Hanratty (2014) and replicatedin Santiago, Hanley, Moore, and Jin (2016). Inthese studies, the authors taught more complexFCRs by expanding the class of responses thatwere placed on extinction to include bothproblem behavior and the simpler form of theFCR. This two-step process, however, may lead503to resurgence of problem behavior, as it did fortwo of three children in Hanley et al. and bothchildren in Santiago et al., or an extinctionburst in some cases. Resurgence of problembehavior may reduce the social acceptability ofthese procedures when applied in relevant contexts or may punish the change agent’sattempts to develop a socially and developmentally appropriate FCR. Progression from a simple response to one of greater complexity mayrequire a more deliberate and gradual shapingof the complex response to prevent the resurgence of problem behavior.In addition to response effort, response efficiency also depends on the schedule and immediacy of reinforcement (Horner & Day, 1991).Horner and Day found that the shorter the timedelay between the presentation of the discriminative stimulus and the delivery of reinforcement, the more efficient the response. Similarly,Derosa, Fisher, and Steege (2015) and Fisheret al. (2018) found that communicationresponse topographies that allow for a shorterduration of exposure to the establishing operations (EO) result in larger and more rapid reductions in problem behavior and decrease thelikelihood of an extinction burst. For example, apicture-exchange communication response canbe prompted more quickly and reliably than avocal communication response, thereby reducingthe amount of EO exposure. More complex andmulticomponent FCRs, such as the one modeled by Hanley et al. (2014), will also result in alonger delay to reinforcement and thus a longerexposure to the evocative context. Therefore, inaddition to the effects of increased effort, thedetrimental effects of the longer delay to reinforcement on the efficiency of the FCR shouldbe considered. One way to address this issuewould be to gradually fade in the full presentation of the evocative context. For example, ascloser approximations of the target FCR areshaped and emitted to the exclusion of problembehavior, longer and more challenging durationsof the evocative context could be presented.

504MAHSHID GHAEMMAGHAMI et al.Finally, the magnitude of reinforcement mayplay a role in increasing response efficiency, andmanipulations of magnitude in favor of the moreeffortful response may increase the probability ofthat response. For example, Athens and Vollmer(2010) demonstrated that providing longerdurations of reinforcement for appropriate communication than for problem behavior resultedin a decrease in problem behavior and anincrease in appropriate communication withoutthe use of extinction. It may be possible to counter the effects of response effort and theincreased delay inherent in emitting a morecomplex FCR by increasing the duration orquality of reinforcement delivered contingent onthese more complex responses.In this study, we describe a set of experiments evaluating the efficacy of a shaping procedure for increasing the complexity ofcommunication responses while minimizing thenegative side effects of the process, such as theresurgence of problem behavior. In addition toincreasing the complexity of the FCR, we alsoincreased the EO exposure at each level andincreased the duration of reinforcement as thecomplexity of the FCR was increased.EXPERIMENT 1In the first experiment, we used a shapingprocedure for progressing from simple to complex FCRs during FCT for the treatment of thehighly impulsive (i.e., short latency to problembehavior upon removal of reinforcers) problembehavior of two children with developmentaldisabilities who communicated using ageappropriate vocal language. Differential reinforcement and extinction were used to shapeapproximations of a complex communicationresponse that included a two-part autocliticframe, appropriate volume and tone of voice,eye-contact, and a pause for acknowledgement.The criterion for reinforcement was graduallyincreased to include more dimensions of thetarget response while exposing the participantto a more complete presentation of the evocative context and included within-session mostto-least prompting of the target FCR. Theefficacy of this shaping procedure for increasingthe complexity of FCRs without a resurgenceof problem behavior or highly emotionalresponding was evaluated in a changing criterion design.MethodParticipants and setting. Two childrenreferred to a university-based outpatient clinicfor assessment and treatment of their severeproblem behavior participated. Jian was a4-year-old boy with a diagnosis of attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) whoengaged in daily episodes of highly disruptivetantrums that included property destructionand aggression. Jeff was a 6-year-old boy with adiagnosis of Asperger’s disorder, ADHD, andgeneralized anxiety disorder. Jeff engaged indaily episodes of highly emotional tantrumsthat included physical and vocal disruptions,aggression, and self-injury. The severity andhighly emotional nature of these tantrums hadresulted in Jeff spending all of his time with hismother and not participating in any formalinstructional contexts such as kindergarten.Both children had age-appropriate language(i.e., full fluent sentences) and play skills andcould follow multistep vocal instructions.All sessions for Jian and Jeff were conductedin 4-m by 3-m treatment rooms equipped witha one-way mirror, audio/video equipment,child-sized tables, chairs, and academic andplay materials. Sessions were conducted 2 to3 days per week, two to six times each day. Sessions were 3 to 5 min during functional analyses and 5 min during FCT.Measurement and interobserver agreement(IOA). Counts of problem behavior and FCRswere collected within 10-s intervals via laptopcomputers and converted to a rate. Problembehavior for Jian and Jeff included aggression

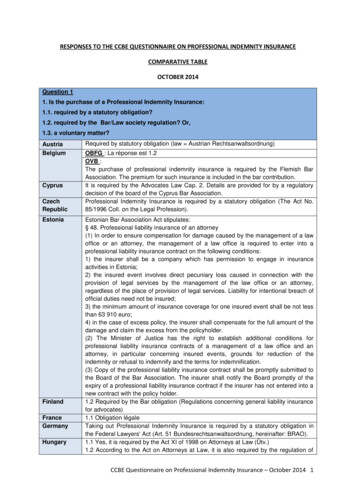

SHAPING COMPLEX COMMUNICATION RESPONSES(hitting, biting, kicking, head-butting, andpushing) and disruptions (physical disruptionssuch as throwing, ripping, swiping, and pushing items, and vocal disruptions such as a highpitch scream). Problem behavior for Jeff alsoincluded self-injury (hand to head or hand tothigh hits).Table 1 summarizes the FCR topographiesand the manner of the presentation of theevocative context at each step. FCRs wereconsidered prompted if the analyst promptedany aspect of the FCR within 10 s of thechild’s FCR. Only independent FCRs arereported.Interobserver agreement (IOA) was assessedby having a second observer collect data on alltargets simultaneously but independentlyduring at least 20% of each phase for both participants. Records were compared on aninterval-by-interval basis, and agreement505percentages were calculated by dividing thesmaller number of responses in each 10-s interval by the larger number. IOA for problembehavior and FCRs averaged 99.5% (range,95%-100%) and 98% (range, 87%-100%)during the functional analysis and 99% (range,92%-100%) and 99.5% (range, 93%-100%)during the treatment analysis, for Jian and Jeff,respectively.Functional assessment process. An open-endedfunctional assessment interview (Hanley, 2012)was conducted for 45 min with each participant’s parents to discover the related topographies of problem behavior and possiblereinforcement contingencies. A 20-min interactive observation of each child in the sessionroom followed (Hanley et al., 2014). is (IISCA) was then conducted, whichinvolved a rapid alternation of test and controlTable 1Criteria for Each Functional Communication Response (FCR) Topography and Manner of Presentation of theEvocative Context for Jian, Jeff, and LukeStepsFCR Criterion for Reinforcement1A vocal mand in a sentence fragment; nocalm voice requirement“My way please”2A vocal mand in an autoclitic frame witha calm voice“May I have my way please?”3A vocal mand in an autoclitic frame witha calm voice and with anattention-seeking response requiringsome eye-contact with the listener“Excuse me may I have my way please?”4A two-part vocal mand in an autocliticframe with a calm voice and with anattention-seeking response requiringsome eye-contact with the listenerwhile pausing for acknowledgementfrom the listener before emitting thesecond part of the mand“Excuse me?”[pause to receiveacknowledgement]“May I have my way please?”Evocative Context Presentation(Jian and Jeff )Touched, but did not remove,preferred items. Simultaneouslypresented a vocal demand, stoppedgranting child’s requests, andwithheld Mom’s attention.Touched, but did not remove,preferred items. Simultaneouslypresented a vocal demand, stoppedgranting child’s requests, andwithheld Mom’s attention.Touched and slightly moved preferreditems toward analyst.Simultaneously presented a vocaldemand, stopped granting child’srequests, and withheld Mom’sattention.Removed preferred items whilelooking away from the child.Simult

D. Leno, Ashley McMullen, and Regina Nastri for their assistance with this project. Correspondence can be directed to mghaemmaghami@pacific.edu Address correspondence to Mahshid Ghaemmaghami, Ph.D., BCBA-D, Department of Psychology, University of the Pacific, 3601 Pacific Ave., Stockton, CA 95211, Tel: 209-946-7311, Email: mghaemmaghami@pacific.edu doi: 10.1002/jaba.468 JOURNAL