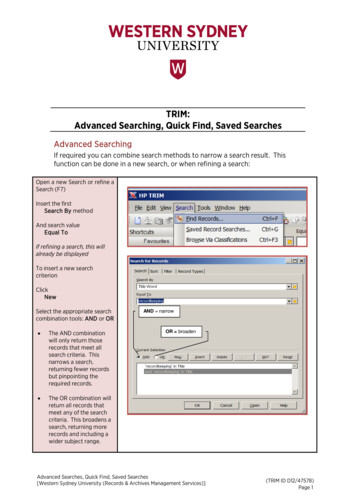

Transcription

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RE CORDS6:1CULTURE ELEMENT DISTRIBUTIONS: XVSALT, DOGS, TOBACCOBYA. L. KROEBERUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES1941

CULTUREELEMENTSALT,DISTRIBUTIONS: XVDOGS, TOBACCOBYA. L. KROEBERANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDSVol. 6, No. 1

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDSEDITORS: A. L. KROEBER, E. W GIFFORD, R. H. LoWIE, R. L. OLSONVolumne 6, No. I, PP. 1-20, I I mapsTransmitted September 6, 1939Issued February I8, 1941Price, 25 centsUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBERKELEY, CALIFORNIACAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESSLONDON, ENGLANDThe University of California publications dealing with anthropological subjects are now issued in two series.The series in American Archaeology and Ethnology, whichwas established in 1903, continues unchanged in format, but isrestricted to papers in which the interpretative element outweighsthe factual or which otherwise are of general interest.The new series, known as Anthropological Records, is issued inphotolithography in a larger size. It consists of monographs whichare documentary, of record nature, or devoted to the presentationprimarily of new data.MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

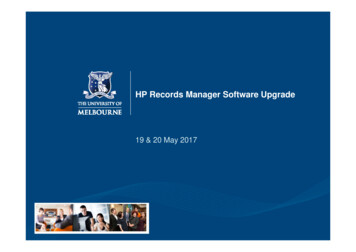

CULTURE ELEMENT DISTRIBUTIONS: XVSALT, DOGS, TOBACCOBYA. L. KROEBERThe field work in the University's CultureElement Survey West of the Rocky Mountains wascompleted in July, 1938.1 Even though theediting and publishing of data will 2equire timeto complete: it seemed desirable to begin interpretive studies. Dr. Driver had indeed alreadymade such a study, and an intensive one, on theGirls' Puberty Rite; but this was begun in 1936,before data were in hand on all areas. I decided to review the materials on several circumscribed topics, as samples of what the listdata would yield when treated nonstatistically,by established methods of distributional ethnography. Salt, tobacco, and dogs were chosenas being relatively concrete and specific subjects. The following three discussions presentthe more important points that emerge from acomparison of the relevant sections of thetwenty blocks of two hundred seventy-nine lists.No attempt has been made to exhaust the materials. Traits that appeared in only part of thelists, whose occurrence proved local or sporadic,or on which the returns were ambiguous, irregular, nonconcordant, or of little apparent significance, were freely omitted from consideration, except in a few instances where deficien-cies in the data seemed to illuminate problemsin the technique of list gathering. I have alsorefrained from making use of the previously published literature, except in special cases.This was deliberate: the paper is designed as atest of how much in the way of significant results old-line ethnologists who distrust coefficients might secure-from our Survey data alone.In the task of extracting data from the lists,notes, and universal negatives'from those of ourlist blocks which are as yet in manuscript, Iwas greatly aided by Dr. Margaret Lantis, whoduring 1938-1939 served'as Ethnologist and thenas Supervisor of a Works Progress Administrat'ionproject partly concerned with the Survey. Infact it would be more accurate to say that shemade herself respo'nsible for the proper extraction of the data. Their clerical compilation,copying of manuscript, and preparation of mapshave been the contribution of other members ofour WPA staff. To all of them my thanks are due.The two hundred seventy-nine particulargroups of Indians dealt with are enumerated andmapped in a preceding issue of this series: myCulture Element Distributions: XI--TribesSurveyed.SALTThe outstanding fact regarding salt in nativewestern North America is that it was used in halfof that area and not used in the other half. Itis the northern half which was saltless. Theline of demarcation is sinuous; but thqre werevirtually no exceptions to the rule that saltwas eaten everywhere to the south and not eateneverywhere to the north of this line.The boundary between the two areas (map 1)begins on the coast at the mouth of the Columbia.The Chinook are without salt, the Tillamook andother Oregon coast groups use it. Of the Kalapuya, the southerly informant affirmed salt, thenortherly one was doubtful; the Tenino said no.The line evidently follows the Cascades south.It then cuts southeasterly across the northeastcorner of California into Nevada, then turnssouth a distance. Salt-using groups in this region are the Shasta, Wintu, Western Achomawi,Maidu, Washo, and Northern Paiute of Pyramid andWalked lakes; nonusers, the Klamath, Modoc,Assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was supplied by the personnel of WorksProjects Administration Official Project No.665-08-3-30, Unit A-15.[1]Eastern Achomawi, Paiute of Surprise Valley, lowerHumboldt River, and lower Carson River. The southernmost point of the dividing line passes betweenWalker and Carson lakes. From here it swings backinto southeastern Oregon, the Northern Paiute ofWinnemucca, Quinn River, and Malheur Lake beingnonusers, the Shoshone of Reese River, Smith Creek,Battle Mountain, and Snake River, also the Paiuteof Owyhee River, being users of salt. The linedoes not follow the Northern Paiute-Shoshoneboundary. Across Snake River the line turns east:the Lemhi and Fort Hall Shoshone do not eat salt,the Great Salt Lake Shoshone, the Gosiute, and theUte do. The Wind River Shoshone of Wyoming arenot included in the Survey.The exceptions are few:The Northwest Coast north of Vancouver Islandeats seaweed, but as "food," not as salt. Moreof this later.The southerly Carrier on up per Fraser Riverare salt-users, though the other north Athabascantribe in the Survey, the Chilcotin, goes with theadjoining Plateau Salish in not using it. It isnot known whether the Carrier constitute a local

2ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDSexception or the fringe of a northern area ofsalt consumption. There is also a questionedaffirmation for the Umatilla.Within the salt area there are the followingdoubtful denials (-, -?, or ? in the lists):Shoshone of Ruby Valley and Ely, Gosiute of DeepCreek (sic 0. Stewart, but J. Steward ), UintahUte. These are separated from one another bysalt-using groups.The upper Yurok, lower Karok, Hupa, andChilula are technically entered as "-" for salt,but all eat seaweed as seasoning.What do the two contrasting areas mean? Thefollowing have been or might be suggested ascauses of nonuse of salt: prevalence of seafood; of a meat diet; of warmer climate. Thefirst will not hold: salt-users extend farthernorth on the coast than inland. As to animalas against plant food, there is no very clearpreponderance of either in either part of theregion considered. Temperature fits the distribution better, but not exactly: the coast ofnorthern California and Oregon is cool and foggy.A climate causing loss of body salt throughsweating might be thought of as causing an increased physiological craving for salt. Thestrongest attachment to salt, as indicated bythe number of deprivation taboos, ritual journeys, and salt ceremonies, evidently exists insouthern California and Arizona, an area generally of long hot summers and heavy evaporation.However, this region constitutes only a smallcore of the distribution of salt use as shown bythe Survey: the peripheral areas are severaltimes as large. It must therefore be concludedthat whatever underlying urge there may be inphysiology as influenced by diet and climate,the specific determinant of salt use or nonusein most instances is social custom, in otherwords culture.2Seaweed.--Along the coast, a dark purplishseaweed, determined as Porphyra perforata forthe Hupa by Goddard, is dried, matted, or pressedinto cakes, and eaten. It undoubtedly has somefood value; but the taste is also definitelysalty and somewhat bitter. In northwest California, this eating is mainly as seasoning orrelish: a piece of the cake is broken off andoccasionally nibbled at between spoonfuls ofacorn gruel. (This is my personal observation.)Presumably the same holds elsewhere in Californiaand Oregon. On the Northwest Coast, the samepurple seaweed, or possibly a related species,is dried into the same cakes, about a foot in2This conclusion differs from that of M. 0.de Mendizabal, Influencia de la sal en la distribucion geografica de los grupos indigenas deMexico, ICA 1928 (New York), 93-100, 1930. Heposits vegetal diet as the primary impulse touse of salt. His paper is valuable, though hismap suffers from areal variability in quantityof data available.diameter, but is then usually cut into morsels,and said to be "eaten as food." As in California,it is also traded to tribes near but off thecoast. The question arises whether the difference is in recorders' nomenclature, the northernlist collectors (Drucker and Barnett) construingas eating of food what the southern ones (Barnett,Driver, Gifford, Harrington) classed with "salt"and therefore construed as seasoning.There is however this difference between thenorthern and southern data which may justify thedistinction. In California and Oregon indubitablesalt is also got from springs or deposits, fromthe ocean, or from burned plants. The Indianstherefore tend to think of seaweed as a sort ofsalt or surrogate; it is a seasoning, not a staple.In British Columbia salt as such is universallydenied, and the seaweed is therefore not onlyspoken of as food but is treated as such. Inother words, the plant may be the same and itsuse is similar, but the attitudes do seem different. It is for this reason that I have rated theBritish Columbia seaweed eaters as nonusers ofsalt in the foregoing discussion.The distribution of the use of this purpleseaweed is peculiar in that there are three areasof use and three of nonuse along the coast (map 2).From southern Alaska to Queen Charlotte Sound theTlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Bella Coola, and mainland Kwakiutl eat the seaweed. The VancouverIsland Kwakiutl use it only as medicine. TheNootka, Gulf of Georgia and Puget Sound Salish,the Klallam, Makah, and Chinook, according toDrucker, Barnett, Gunther, and Ray, do not use itat all. An exception is formed by the Comox andPentlatch of Vancouver Island,3 near the northernend of the Gulf of Georgia; this may be an extension from the eating habits of the mainland Kwakiutl not far to their north.With the Tillamook, seaweed use recommences,and continues as far as the Coast Yuki, includingnearer inland tribes like the Karok, Hupa, Nongatl,Lassik, and Kato, but not the Chimariko and Yuki.4For the Pomo area, there are only negatives, except for the Makahmo Pomo of Cloverdale, an inlandgroup! I doubt many of these Pomo negatives.South of San Francisco, Harrington records seaweed for the San Juan Bautista Costano, both hisSalinan groups, and the Santa Inez and Santa Barbara Chumash, most of them not immediately on thecoast. For the Ventureno and Gabrielino he hasno entries, which probably means that they did notuse it, since Drucker records universal negativesfor the Luiseno and Diegueno.This intermittent distribution is due to culture, not ecology. As the following records show,Porphyra perforata occurs along the whole coast;two of its subspecies from the Mexican border at30f the two Slaiamun lists, one has , one -.a note for Kato and Lassik: eatenas food, replaces salt while available.4Essene has

Map1.Salt used.Map 3. Saltfrom grass.Map 2.Map 4.Salt: seaweed.Salt taboo in ritual.

ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS4least to Washington;to British Columbia;to Vancouver Island;cluding one noted asanother species from therefour species from Montereyand two are Alaskan, ineaten by Indians.Botanical distribution of Porphyra.--Theserecords on the occurrence of the genus are dueto the courtesy of Dr. H. L. Mason: the listrepresents localities of specimens in the University Herbarium.Porphyra perforata appears to have a continuous distribution from Alaska to Mexico. Of morethan thirty specimens in the Herbarium, five arefrom Alaska: Glacier Bay, Sitka, Seldina, Baranoff and Shumagin islands. British Columbia isrepresented by Victoria and "Vancouver Island";Washington by six localities, including PugetSound; Oregon by two. Fort Ross and threepoints in Marin County show that the alga is notlacking where the Indians appear not to haveused it in the stretch of coast north of SanFrancisco. For southern California, there arespecimens from San Simeon, Santa Rosa Island,and San Diego. In all regions of nonuse, customrather than nonoccurrence of the plant is accordingly the cause; though there may well havebeen local stretches of shore where it was notavailable.P. perforata f. lanceolata specimens rangefrom San Diego to Chehalis Bay; f. segregatafrom Mexican California to Puget Sound.The known range of other species of Porphyrais as follows:P. abyssicola, from San Diego to Sidney,British Columbia.P. ainiata, variegata, naiadum, from Montereyto Vancouver Island.P. nereocystis, from Monterey to Uyak Bay andKodiak, Alaska.P. tenuissima, from Alaska only: Yakutat,Sitka, Baranoff.P. laciniata is represented by eight Alaskanlocalities including the Pribylov Islands, andfrom Chile (!). The Yakutat specimen is accompanied by the legend: "The kind of seaweedIndians cook [sic] and eat."Salt burned out of grass.--In parts of California and Nevada, a certain grass was roastedor burned in a pit, in the bottom of which "salt"would then collect. The first fuller description is from the Valley Patwin of Colusa;5 E.Voegelin's notes contain a similar account fromthe Valley Maidu of Chico. Voegelin is the onlyone to identify the plant: Distichlis spicata,salt grass according to Jepson,6 who gives asthe habitat "salt marshes and alkaline soil,low altitudes, common along the coast, and inthe interior valleys and deserts; extends fromsouthern British America to Mexico." Pendingfurther verification we can assume that whereverFUC-PAAE 29:280, 1932.6Manual94, 1925.of the Flowering Plants of California,a grass is burned for salt in this part of theworld it is Distichlis, except perhaps in easternNevada.Map 3 shows that this salt roasting has a muchnarrower distribution than the plant. Its mainarea is the Central Valley of California. Thus,of 12 Yokuts tribes, 11 burned grass, togetherwith 5 out of 7 Mono and both Tiibatulabal divisions; 5 of 8 Miwok groups, 3 of 6 Maidu-Nisenan;there is no reported case from the north end ofthe valley. Beyond, there are scattering casesonly: 2 in Russian River drainage, 3 in Eel, 1 onthe lower Klamath. South of the Great Valley, thepractice is universally denied. East of theSierra Nevada, J. Steward secured 5 affirmationsof "brush burned" for salt; 1 from Owens Valley(burning from grass denied by Driver's informants),and 4 from scattered Shoshone bands in easternNevada.It is reasonably clear that what we have hereis a practice substituted for the gathering ofmineral salt, or sometimes added to it, accordingto opportunities of local environment. Grassburning never displaces mineral salt gatheringover any considerable area: the two habits occurinterdigitated, not infrequently among the samegroup. Thus while most of the Yokuts--prevailingly a people of the valley plains and lowerfoothills--burned grass, the Choinimni divisionused a mineral supply, and the Nutunutu, Chukchansi, and San Joaquin Yokuts used both. For7 Mono groups, the figures are: grass only, 3;mineral only, 2; both, 2; for 6 Maidu: dry mineral, 6; salt spring or marsh, 3; grass burned, 3.In southern California, where salt from burnedgrass is universally denied, 5 informants--Serrano,Cahuilla, Luiseno, Cupeno--spoke of salt being"collected from grass," presumably rubbed orstripped off. This suggests the Yaudanchi Yokutspractice of beating the salty juice out of Alitgrass (Handbook, 530).Inorganic sources of supply.--These of coursevary endlessly in character according to localtopography and geology. We have some rather tantalizing entries, as: "from the ocean," "frombeach rocks," "from kelp," "ocean water as seasoning," "alkali." Other descriptions are: frommineral, dry mineral, from springs, from saltmarsh, from salt lake, from playa, mineral onsurface, mineral dug from stalactites, from cavesor rocks, ashes in bread, mush, or herbs; also,not infrequently, got by trade. There are excellent local notes from a number of tribes, especially in the lists for Northwest California, Pomo,Yana, Northeast California, Miwok, the Basin Shoshoneans, and the Pueblo-Apache area. The mainvalue of these is for topographic ecology, andthey will not be considered further in the present comparative survey.Preservation of food by salt.--It has beengenerally assumed that the Indians merely dried

CULTURE ELEM. DISTRIB.: XV--KROEBER: SALT, DOGS, TOBACCOtheir meat and fish, without salting it. Probably this point should have been inquired into,rather than being assumed and left out of mostof the lists. In two blocks of lists preservation by salting appears, apparently throughhaving been volunteered by informants. For 16Northeast California lists Voegelin has theseentries. "Fish salted": , Trinity Wintu, Valley Maidu; ( ), Foothill Maidu, Atsugewi; -, allothers. "Dried meat, salted or plain": all ,except - for Eastern and Western Achomawi andMcCloud Wintu. For the Central Sierra, in 13lists, Aginsky gives "Fish" (and again separately "Meat") "stored in baskets with salt": , 2 Northern Miwok groups; all others, no entry.It may be that this was a native habit in someareas. The matter should ceitainly be reinquired into. However, it is more than eightyyears since the white man overran the localities in questiona; and until there are furtherdata which have been cross-checked for the point,I incline to believe that an occasional informant confuaed post-Caucasian and pre-Caucasianpractice. If the habit were old, more of the150 informants in the salt-using area would presumably have forced it on the recorders' attention.Salt in ritual.--The most general appearanceof salt in religion in western North America isas something tabooed on ritual occasions, especially those connected with rites of passage.The distribution of such taboos is, as might beexpected, more restricted than that of the useof salt. A thing must be both fairly obtainableand fairly desirable before there would ordinarily be much motivation toward forbidding it.As map 4 shows, certain peripheral regions ofsalt use do not impose salt taboos. These regions are: the coast (including tracts inland tothe Sacramento River) from San Francisco Bay tothe Columbia River; the Shoshone and Ute territories; those inhabited by the Athabascans ofthe Southwest except to a minor extent the morenortherly and westerly groups; and perhaps thePueblos also, although no list inquiries onritual were made among them. This leaves as theheart of the salt-taboo area western Arizona,southern California, and the Central Valley ofCalifornia, with some extension of the latter onboth sides to the central coast region and thenearer of the Northern Paiute groups.The taboos, endlessly variable, group intoclasses according to occasion: Birth; Girls'Puberty; Menstruation; Death and Mourning; Initiation, Boys' Puberty, or Vision Quest. Birthtaboos may refer to pregnancy or to postbirthrestrictions on the mother, the father, or both.The other classes tend to subdivide analogously.In general, if the salt taboo is rigorous forone occasion, it tends to extend to others whichare ritualized. Thus, in the Yuman-Piman area,where War-preparation and Enemy-slayer purifica-5tion are emphasized, the salt taboo extends tothem. Similarly for Initiation in southern California and among the Maidu. On the other hand,the Pomo also initiate, but having no salt taboofor crisis rites, do without it on initiation.Of course the weight of the occasion also counts.If there are frequent but not universal Birthtaboos in an area, they are likely to be put morefrequently on the nursing mother than on the father. Thus of 23 southern Sierra groups, 16 forbid salt to the mother, only 7 to the father, andthese 7 are geographically scattered. The California "semicouvade" is not a "classical" couvadespecializing on the father, but has previouslybeen recognized as a joint parental affair, withall or part of the mother's restrictions extendedto the father.Incidentally, this last example illustratesthe manner in which a wealth of comparative dataon specific items can illuminate problems of cultural process and cultural direction or emphasis.Driver's data relate to 10 Yokuts tribes. Allthese taboo salt for the mother, except 2 adjacent southerly ones, the Yaudanchi and Paleuyami.For the father, the southern exception growsareally by the addition of the Yauelmani and Wuknhaimni; but 2 northern tribes, the Chukaimina andNutunutu, also except him. When it comes to girls'puberty, the Chukaimina and Nutunutu are backamong the salt-tabooing tribes, but another northern tribe, the Kocheyali, does not salt-taboo theadolescent girl. For menstruation, only theChukaimina and lake tribes (Nutunutu, Tachi, Chunut) impose the restriction. At death, the kinmourners abstain from salt among the same 4 tribesand the Choinimni. In summary, we have 2 tribes,the Yaudanchi and Paleuyami, who profess to useno salt taboo in any crisis situation, not evenfor the mother at birth. We have a larger group-Chukaimina, Nutunutu, Tachi, Chunut--who imposeit not only on the mother but also at puberty,menstruation, and death; half of them do and halfdo not extend it to the father at birth. The remaining 4 tribes--Yauelmani, Wukohamni, Choinimni,Kocheyali--adhere once with one group and thenwith the other. Apart from the groupings, therelative "strength" of the several occasions, asshown by the number of tribal participations, is:strongest, mother at birth; next, girl's pubertyand death; weakest, menstruation and father atbirth. It is evident that the preoccupation ofYokuts culture is greater with birth than withmaturity or death, greater with the mother thanwith the father of a child, greater with theadolescent than with the grown woman. There isindication here of what is primary and more stablein the pattern, and what is secondary and morechangeable.If we consider the scattering cases of salttaboo outside the core area (Maidu to Pima),their reference is as follows: Birth (mother,father, both, or pregnancy), 29; Girls' Puberty,12; Menstruation, 12; Death, 1; Initiation

6ANTHROPOLOGICAL RECORDS(really boy's vision quest), 2. Nearly all thelists consider the topics in this order, and itis conceivable that occasional informants orrecorders tired under repetition and skimpedlater cases. But even with some allowance forthis possibility, it is evident that in themarginal areas of salt taboo, birth is felt asa definitely important and death as a relativelyunimportant occasion for its application. It isalso evident that in these marginal areas thereis so little difference of emphasis betweenfirst menstruation and recurrent menstruation,that, contrary to the Yokuts attitude, adolescence in the girl is scarcely singled out ascrucial but rather is considered as already partof her mature functioning.I have designated the strip from the Maidu tothe Pima as the core of the area in which salttaboos are imposed (map 4). Within this core,however, a nucleus is evident where taboos areimposed on additional occasions and where thereare some positive ritual associations. Thisnucleus consists of the southernmost part of thecore area: southern California, Yuman tribes,Pima and Papago, and a few Southern Paiute bandsunder Yuman influence.All southern California groups taboo salt forthe boy who is undergoing his puberty initiation.Most of them, especially the Shoshonean ones,extend the menstruant woman's taboo to her husband. Some of the Yuman groups, but not theShoshonean ones, impose the taboo either on theburier or on the widow of a dead man.In the Yuman-Piman area, in western Arizona,we find the following salt taboos:Pre-war-party fast: Cocopa.Purification of enemy slayer: Papago, Pima,Maricopa, Cocopa, Mohave, Shivwits Paiute.Girl's tattooing: Pima, Maricopa, Yavapai,Mohave.Boys' puberty: Maricopa, Walapai, Cocopa,Akwatala, Mexican DieguefTo.Husband of menstruant woman: Maricopa, Yavapai, Walapai, Mohave, Akwa'ala.Mourners, or the ritual runners in the deathcommemoration: Maricopa, Yuma, Mohave, Chemehuevi Akwa'ala, Mexican Dieguefno.A 6alt cycle of songs and myth is sung by theChemehuevi, Shivwits, Mohave, Walapai, Maricopa. 7Finally, the Papago practice an elaborateritualized journey to the sea to get salt. BothGifford and Drucker obtained accounts of this intheir lists, and it appears to be as sacred anaffair as the Zuni expeditions to their saltlake. It may be as old as the Zuni rite orolder. The Zuni salt lake was visited by othertribes. Gifford mentions the Hopi, EasternNavaho, and Warm Springs and Huachuca Chiricahuaas taking salt from it with a certain amount ofritual. Apparently the Zuni invested their saltjourney with the heaviest elaboration of ceremony, possibly adopting the idea from the Papagojourney to the ocean. So far as the other Pueblos and Apache-Navaho ritualized salt expeditions,it seems to have been with reference to the Zu-niholy lake.DOGSSeveral of the twenty blocks of lists are defective on dogs, in that they did not specifically inquire whether the animal was kept at all,whether it was bred or obtained from outside,whether it was housed or otherwise cared for.This is true of the original Yana and Pomo lists;also for the four Great Basin ones which derivefrom Julian Steward's Nevada Shoshone one. Inthe former instance the responsibility is mine.Gifford's list was built up from my presurveyone, and I passed upon his additions. Moreover,I was present at the filling of the list fromone tribe, the Lake Miwok, and should have observed the gap. This gap is the more unfortunate because the Pomo-Miwok region is an area inwhich dogs were generally not raised or kept.All I can say is that this is a point at whichwe slipped into the fault that almost everyethnographer sooner or later commits, but whichthe lists were designed to prevent: to assume a7Sung by Maricopa old men and women when anenemy was killed or captured. Spier, YumanTribes of the Gila River, 268, 1933.phenomenon, or its absence, instead of specifically inquiring into its occurrence.Fortunately there are in all lists some references to the use of dogs, as for hunting, and mentions in the notes, which allow at least approximate conclusions on most matters of interest.Domestication.--Although it is generallyassumed that the dog is man's universal companionand dependent, this is of course not quite accurate. There are dogless tribes in South America;and an area half encircling San Francisco Bay onthe north and east has now to be added.Dogs were not entirely lacking in this region.All the local languages have a word for the animal. But dogs were not kept regularly; they weresecured as scattered individuals from outside;they would be bought and would be taken care ofas prized pets, somewhat as we keep parrots ormonkeys; and-they were not used ordinarily forhunting or other useful purpose. The crucialpoint seems to be that they remained rare enoughfor a local breed not to develop. The dog therefore was known to these cultures, entered into

CULTURE ELEM. DISTRIB.: XV--KROEBER: SALT, DOGS, TOBACCOthem as an occasional luxury element, but not asa normal feature or with a standardized function.These are the data:7Of the two, the scarcity may be assumed as prior.It is indeed conceivable that an interest andconcern in dogs might spring up of itself: Lintonhas given such a case for the Comanche.8 But itis hardly conceivable that a people having suchan interest should then proceed to get rid of allor nearly all their dogs. We must rather concludethat the tribes of this area first lost the habitof keeping dogs,9 and then sporadically began toreimport individual animals as something curiousand interesting. What caused the loss is obscure.The archaeological evidence corroborates thelist survey findings. Heizer and Hewes,10 incollecting instances of prehistoric ceremonialburial of bears) coyotes, deer, eagles, and otheranimals in central California, especially in theregion of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, pointout that there is no record of the discovery ofdog bones, either in deposits which appear archaeologically late or those which seem early. Thiswould argue that at least in the region occupiedby the historic Plains and Northern Miwok, Nisenan,and Patwin, the absence of regular keeping orbreeding of dogs is an old matter.Heizer and Hewes's data further suggest thatwhile certain of the animals may have been caughtfor use in ritual, at least some were taken young,reared as pets, and then formally buried whenthey died, or perhaps, in the case of bears, afterhaving to be killed when they became large anddangerous. These ancient indications of pet keeping, not very frequently but with much fuss whenit did happen, fit in exactly with the attitudesof the historic tribes of the region in regard todogs.Mattole: not bred; a few obtained from thenorth.Sinkyone: two informants-in conflict.Kato: dogs kept and used in deer hunting; butfew, and rarely bred; usually secured fromWailaki to NE.Lassik: same as Kato; mostly got from Nongatlto N.Yuki: not remembered whether bred; securedfrom Wintun.The three last-mentioned tribes got most oftheir dogs in trade, regarded them as valuable,and buried them like persons, sometimes withshell money.Coast Yuki: no dogs.Sixteen Pomo tribelets: only two admittedusing dogs for hunting (Shanel North and Makahmo).These two informants probably were thinking inpost-Caucasian terms. It is a full centurysince the Mexicans began to colonize Pomo habitat. Only four tribelets (Kabedile, Kacha,Icheche, and Makahmo) admitted dogs being named;and this is no evidence of their being commonbecause the Kato, Lassik, and Yuki named theirscarce dogs. Kabedile: three informants independently denied dogs were kept. Yokaia: "

For the Pomo area, there are only negatives, ex-cept for the Makahmo Pomo of Cloverdale, an inland group! I doubt many of these Pomo negatives. South of San Francisco, Harrington records sea-weed for the San Juan Bautista Costano, both his Salinan groups, and the Santa Inez and Santa Bar-bara Chumash, most of them not immediately on the coast.