Transcription

Comments from the American Board of Family MedicineRevision of Duty Hours Requirements in the ACGME Common Program RequirementsThe ABFM is pleased to respond to your request for input on accreditation requirements for resident dutyhours for consideration by the Phase I Task Force.A review of the literature reveals that the 2003 and 2011 duty hour policies have been insufficiently studiedfor effect on the central reasons for their implementation, namely patient safety and resident well-being,and most research has focused on inpatient care. We recognize that the 2003 policy was a response toboth herald cases of patient harms associated with fatigued and poorly supervised residents, and withvariable duty hour policies across RRCs that were also inconsistently applied. The 2011 modification,triggered by the related, 2009 Institute of Medicine report, made further modifications, specifically to clarifytotal hours of work and instruction and to clarify supervision requirements. We found several studiesrelevant to the impact of these policies, most of which are survey-based and of poor to fair quality, andsummarize some of the best and most relevant to family medicine. A few studies looked objectively atimpact of these policies on training outcomes other than fatigue, safety or well-being. The few studies thatevaluated primary outcomes using pre/post analyses suffer from many other coincidental health systemchanges, making it difficult to understand causal relationships, but did show no changes in patientmortality.1,2 A few benchmark studies of the 2003 duty hours policy impact on surgical outcomes andadverse drug events in hospitals did not show improvement.3,4 We have heard anecdotally that a controlledtrial underway in surgery residency programs was recently challenged in court. Impact in primary careprograms for the 2003 and 2011 policies have had relatively little research or evaluation.A study of related policies in Canadian medical education used semi-structured interviews with faculty toreach the conclusion that there was a need for flexibility based on specialty-specific factors.5 The Canadianfaculty perceived clinical care gaps related to duty hour restrictions, and that these gaps also affectedquality of education, preparedness for practice, care continuity, and provider well-being (figure). The leadauthor of the Canadian, qualitative study, was a resident associated with the National Steering Committeeon Resident Duty Hours, and both the paper and the Steering Committee concluded that specialty-specifictraining needs should considered. A recent randomized, crossover study in a single US institutionsubstantiates the Canadian concerns, finding that the change to the 2011 duty hour policies resulted inmore sleep for internal medicine residents, particularly interns, but decreased educational opportunities,increased patient handoffs, and increased perceived decline in care quality (by nurses and residents).6 Arelated study of residency graduates from South Carolina Area Health Education Consortium-affiliatedfamily medicine residency programs from 2005 to 2009 found that while the vast majority felt that the 2003ACGME policies did not adversely affect their preparedness for practice (97%), 20% of them felt that theydid not have adequate supervision.7 Interestingly, 81% said that they worked fewer hours in practice thanin residency.

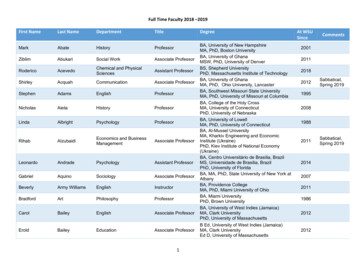

January 28, 2016Page 2From: Wu PE, Stroud L, McDonald-Blumer H, Wong BM. Understanding the effect of resident duty hourreform: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(2):E115-120.A study at the University of Missouri found that the 2011 work hour policies erased gains made in priorinstitutional efforts to increase resident continuity clinic experience as part of the Preparing the PersonalPhysician for Practice (P4) Initiative, a national program heralded by Dr. David Leach while he still servedat the ACGME.8-10 The duty hours impact was due, in large part, to the creation of night-float residentteams which limited post-call clinic time and time spent in inpatient and outpatient settings. Quantitatively,total resident visits declined by more than 4,000, annually. Missouri’s informal feedback from other P4Initiative partners was that they experienced a similar reversal of P4 outcomes, namely reduced inpatientand outpatient experience, but increased consideration of lengthening training, and increased collaborationwith other providers. The University of Washington Family Medicine Network (UWFMN) residencies havecollaborated for more than a decade in collecting and comparing data regarding the productivity andoperations of their training programs to identify the program-level effects of a variety of environmentalchanges, including duty hours.11 Their study of the decade 2000-2010 found that resident outpatient visitsdeclined by 17.2% (PGY3 declined the most, 21%), inpatient visits declined 22.4%, NP/PA visits/FTEincreased by 12.7%, and total core faculty FTE increased by 12%. While they acknowledge that electronichealth record (EHR) and Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) implementation co-occurred with dutyhours, the aggregate impact was a reduction in resident clinical productivity, especially for senior residents,and a transfer of activity to faculty and NPs and PAs.To understand resident perspectives about the 2011 ACGME Common Program Requirements, ananonymous, electronic resident survey was sent to 123 Designated Institutional Officials in December 2011for distribution to residents.12 Sixty-one family medicine programs participated (potentially 2,956 familymedicine residents) and nearly 1/3rd of family medicine residents (928, 31.4%) responded. The surveycoincided with the implementation of the 2011 ACGME policies allowing a pre-post evaluation of responses(recognizing that interns in that year would be PGY2’s the following year, thus reporters shifted duringimplementation). The authors report nearly half (47.4%) disapproved of the 2011 changes and nearly aquarter (24.6%) approved of the changes. PGY1 family medicine residents were more likely to reportimproved rest, patient safety, education, and overall approval than were PGY2/3, but across the wholesample, more than half thought the change was worse for preparing residents for senior resident role(56.6%) and for senior resident quality of life (53.2%). The majority thought that it made senior residentlives harder (68.5%), and 77.9% thought handoff frequency increased. The majority felt that availability ofsupervision (72.7%) and patient safety (52.2%) were unchanged. Several studies in different specialties

January 28, 2016Page 3corroborate this shift of work to more senior residents and faculty, from both the 2003 and 2011 work hourspolicies.13,14 In 2007, a survey of family medicine residency faculty (55% response rate) 19% felt that(2003) duty hour policies had increased faculty work hours and nearly the same percentage (20%) wereconsidering leaving academics related to this change.15Our specialty societies recently endorsed family medicine Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs). Ourcolleagues in the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine who helped lead this activity made a special pleafor specialty flexibility with duty hours in order to support implementation of the EPAs. Specifically, theybelieve that strict duty hours tread on continuity, a core EPA shared across primary care specialties, anda facilitator of other EPAs that build upon enduring healing relationships. Robert Woollard, commenting onthe similar duty hour policies put in place in Canada, referred to this duty-hour problem as a dilution ofrelationships that is unsupportive of the need for health care institutions to become complex adaptivesystems.16 Dr. Woollard calls for a return to “effective healing relationships that endure over time and overplace of care,” that are sine qua non of family medicine, and to “enduring generalist relationships.” Knowingthe value of continuity to the Triple Aim for Healthcare, we endorse this proposition that duty hours shouldnot trump opportunity to preserve and learn from continuity relationships across care delivery settings.17,18We are also concerned about the risk to comprehensiveness, another tenet of primary care, and one thatis associated with lower healthcare spending.19 A study of family medicine graduates in South Carolinaimmediately before (1999-2003) and after (2005-2009) the initial ACGME duty hours found significantreductions in family physician preparedness for office-based surgery (OR 0.50), reduction in specificprocedures or care settings (reduced ICU care, nursing home care, and hospital care, flexiblesigmoidoscopy, central line placement, and ventilator management), and reduction in taking after-hourscall (22.3% vs 8.6%).20Dr. Joseph Gravel, current ABFM board member, and other leading residency directors in 2011 raised theconcern that as duty hour rules (2011) diminished the effective amount of training time, “we owe it to ourresidents and the public to honestly and actively study the length of family medicine residency training tominimize the unintended impact of duty hour restrictions.”21 The ABFM recognizes the safety, ethical, andpolitical concerns that led to the 2003 and 2011 ACGME duty hours policies; however, the ABFM isconcerned that the pendulum has swung too far and risks producing a primary care workforce that has lessappreciation for continuity, less ability to provide comprehensive care, and less capacity to coordinate thecomplex care needed in order to achieve the Triple Aim for Healthcare. This was also the opinion of themajority of Family Medicine Program Directors in 2009. 22 The ABFM agrees with the majority of familymedicine residency directors (83%) and residents that 60-80 hour work-weeks are desirable for residentsand that there is a role for duty hour policies.23,24 We also believe that most family medicine residencyprograms have demonstrated sufficient fidelity to duty hours policy and implementation of trackingmechanisms that they can be verifiably trusted to manage more flexible duty hour rules. The ABFMformally requests that the ACGME consider modification of the Common Program Requirements to allowsufficient flexibility to balance needs for adequate rest while permitting greater continuity,comprehensiveness and care coordination goals for training. The ABFM also calls for better research tosupport and evaluate next-generation duty hours rules.

January 28, 2016Page p KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, et al. Mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiariesin the first 2 years following ACGME resident duty hour reform. JAMA. 2007;298(9):975-983.Volpp KG, Rosen AK, Rosenbaum PR, et al. Did duty hour reform lead to better outcomes amongthe highest risk patients? J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(10):1149-1155.Poulose BK, Ray WA, Arbogast PG, et al. Resident Work Hour Limits and Patient Safety. Annals ofSurgery. 2005;241(6):847-860.Mycyk MB, McDaniel MR, Fotis MA, Regalado J. Hospitalwide adverse drug events before andafter limiting weekly work hours of medical residents to 80. Am J Health Syst Pharm.2005;62(15):1592-1595.Wu PE, Stroud L, McDonald-Blumer H, Wong BM. Understanding the effect of resident duty hourreform: a qualitative study. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(2):E115-120.Desai SV, Feldman L, Brown L, et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation-compliantmodels on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicinehouse staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649-655.Peterson LE, Diaz V, Dickerson LM, Player MS, Carek PJ. Recent Family Medicine ResidencyGraduates' Perceptions of Resident Duty Hour Restrictions. Journal of Graduate Medical Education.2013;5(1):31-35.Lindbloom EJ, Ringdahl E. Resident duty hour changes: impact in the patient-centered medicalhome. Fam Med. 2014;46(6):463-466.Green LA, Jones SM, Fetter GJ, Pugno PA. Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice: ChangingFamily Medicine Residency Training to Enable New Model Practice. Academic Medicine.2007;82(12):1220-1227 1210.1097/ACM.1220b1013e318159d318070.Leach DC, Batalden PB. Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4): Redesigning FamilyMedicine Residencies: New Wine, New Wineskins, Learning, Unlearning, and a Journey toAuthenticity. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2007;20(4):342-347.Lesko S, Hughes L, Fitch W, Pauwels J. Ten-year trends in family medicine residency productivityand staffing: impact of electronic health records, resident duty hours, and the medical home. FamMed. 2012;44(2):83-89.Drolet BC, Anandarajah G, Fischer SA. The impact of 2011 duty hours requirements on familymedicine residents. Fam Med. 2014;46(3):215-218.Jamal MH, Rousseau MC, Hanna WC, Doi SA, Meterissian S, Snell L. Effect of the ACGME dutyhours restrictions on surgical residents and faculty: a systematic review. Academic medicine :journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2011;86(1):34-42.Dennis BM, Long EL, Zamperini KM, Nakayama DK. The effect of the 16-hour intern workdayrestriction on surgical residents' in-hospital activities. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(6):800-805.Choby B, Passmore C. Faculty perceptions of the ACGME resident duty hour regulations in familymedicine. Fam Med. 2007;39(6):392-398.Woollard RF. When evidence and common sense collide: Resident hours and systems of care.Canadian Family Physician. 2013;59(2):125-127.Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 Building Blocks of HighPerforming Primary Care. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(2):166-171.Saultz JW, Lochner J. Interpersonal Continuity of Care and Care Outcomes: A Critical Review. TheAnnals of Family Medicine. 2005;3(2):159-166.

January 28, 2016Page 519.20.21.22.23.24.Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL. More Comprehensive Care Among FamilyPhysicians is Associated with Lower Costs and Fe

28.01.2016 · Dr. Joseph Gravel, current ABFM board member, and other leading residency directors in 2011 raised the concern that as duty hour rules (2011) diminished the effective amount of training time, “we owe it to our residents and the public to honestly and actively study the length of family medicine residency training to