Transcription

A Lawyer’s Guideto Detectingand PreventingMoney LaunderingA collaborative publication of theInternational Bar Association, theAmerican Bar Association and the Councilof Bars and Law Societies of EuropeOctober 2014

This Guide has been prepared by working groups of the InternationalBar Association (“IBA”) (led by Stephen Revell), the American BarAssociation (“ABA”) (led by Kevin Shepherd) and the Council of Barsand Law Societies of Europe (“CCBE”) with the help of Dr S. ChandraMohan (Associate Professor of Law) and Lynn Kan (Juris Doctor),Singapore Management University, School of Law.Contents of the GuideExecutive Summary2I.3Introduction and BackgroundII. Sources of the Legal Profession’s AML Responsibilities11III. Vulnerabilities of the Legal Profession to Money Laundering23IV. The Risk-Based Approach and Money Laundering Red Flags27V.39Case StudiesVI. Glossary and Further Resources48Endnotes52Disclaimer:This Guide has been prepared and published for informational and educational purposes only and should notbe construed as legal advice. The laws and regulations discussed in this Guide are complex and subject tofrequent change and the reader should review and understand the laws and regulations that are applicable tothe reader (which may involve the laws and regulations of more than one country) and not rely solely on thisGuide. The IBA, ABA and CCBE assume no responsibility for the accuracy or timeliness of any informationprovided herein, or for updating the information in this Guide. For further information on applicable laws andregulations a reader may visit the following website of the IBA which aims to give country by countryinformation provided by correspondents in each country – px.In addition, readers should carefully consider the legal and regulatory issues in their own countries by referringto their bar association or law society for country specific guidance on anti-money laundering issues.A Lawyer’s Guide to Detecting and Preventing Money Laundering1

Executive SummaryMoney laundering and terrorist financingrepresent serious threats to life and society andresult in violence, fuel further criminal activity,and threaten the foundations of the rule of law(in its broadest sense). Given a lawyer’s role insociety and inherent professional and otherobligations and standards, lawyers must at alltimes act with integrity, uphold the rule of lawand be careful not to facilitate any criminalactivity. This requires lawyers to be constantlyaware of the threat of criminals seeking tomisuse the legal profession in pursuit of moneylaundering and terrorist financing activities.While bar associations around the world play akey role in educating the legal profession, theonus remains on individual lawyers and on lawfirms to ensure that they are aware of andcomply with their anti-money laundering(“AML”) obligations. These obligations stemprimarily from two sources:(i) the essential ethics of the legal professionincluding an obligation not to support orfacilitate criminal activity; and(ii) in many countries, specific laws andregulations that have been extended tolawyers and require, in a formal sense,lawyers to take specific actions. Thesetypically include an obligation to conductappropriate due diligence about clients witha view to identifying those that may beinvolved in money laundering and, in somejurisdictions, an obligation to inform theauthorities if they suspect clients and/or thepersons the client is dealing with may beinvolved in money laundering. Thisobligation to report is highly controversialand is seen by many to endanger theindependence of the legal profession and tobe incompatible with the lawyer-clientrelationship. However, in some countrieslawyers can themselves be prosecuted for afailure to carry out appropriate due diligenceand report suspicious transactions to theauthorities. Although we may not agreewith or support such an approach, it isimportant that lawyers in such countriesare fully aware of these obligations and theactions they need to take.2All lawyers must be aware of and continuouslyeducate themselves about the relevant legal andethical obligations that apply to their homejurisdiction and other jurisdictions in whichthey practice, and the risks that are relevant totheir practice area and their clients in thosejurisdictions. This is particularly so as themoney laundering and terrorist financingactivities of criminals are rapidly and constantlyevolving to become more sophisticated.Awareness, vigilance, recognising red flagindicators and caution are a lawyer’s best toolsin assessing situations that might give rise toconcerns of money laundering and terroristfinancing. Such situations may, in somecountries, result in (i) the lawyer being foundguilty of an offence of supporting moneylaundering, due to the failure to properly“check” clients or report suspicious transactionswhere it is required and (ii) the lawyer beingsubject to professional discipline.This Guide is intended as a resource to be usedby lawyers and law firms to highlight theethical and professional concerns relating toAML and to help lawyers and law firms complywith their legal obligations in countries wherethey apply. Clearly, this Guide does not imposeany obligations on a lawyer. In it you will find:(i) a summary of certain international andnational sources of AML obligations (Part II);(ii) a discussion of the vulnerabilities of thelegal profession to misuse by criminals inthe context of money laundering (Part III);(iii) a discussion of the risk-based approach todetecting red flags, red flag indicators ofmoney laundering activities and how torespond to them (Part IV); and(iv) case studies to illustrate how red flags mayarise in the context of providing legal advice(Part V).This Guide is not a ‘manual’ which will ensurethat lawyers satisfy their AML obligations.Rather, it aims to provide professionals withpractical guidance to develop their own riskbased approaches to AML compliance which aresuited to their practices.A Lawyer’s Guide to Detecting and Preventing Money Laundering

I. Introductionand Background3

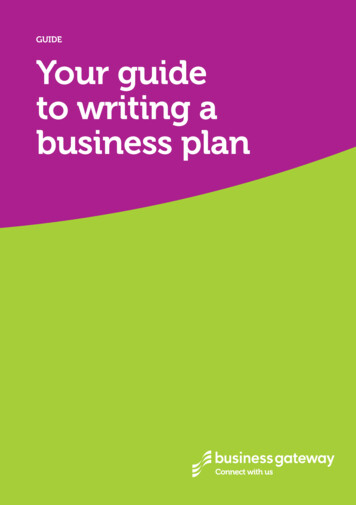

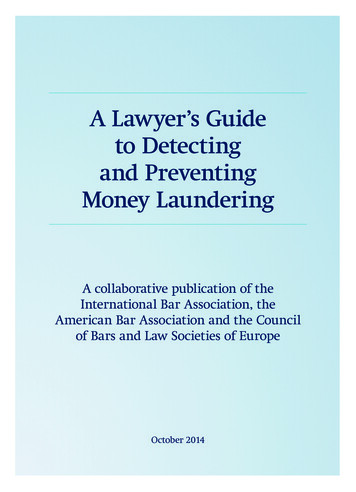

I. Introduction and BackgroundMoney laundering (the conversion of proceeds from crime into legitimate currency orother assets) and terrorist financing (whether from the proceeds of crime or otherwise)are not new phenomena. Criminals have been concealing the illicit origins of moneythrough money laundering for decades. However, the scale of such activity has grownsignificantly – a 2009 estimate of the extent of money laundering put it at a staggering2.7% of the world’s gross domestic product (or US 1.6 trillion).1Measures combatting money laundering and terrorist financing overlap to a large extent,as criminals engaging in either of these activities are looking to transfer money whileconcealing the origin and destination of the funds. Further special considerations,however, apply in the fight against terrorist financing. Although this Guide focuses onanti-money laundering (“AML”) compliance and does not purport to tackle comprehensivelythe issue of the legal profession’s role in the fight against terrorist financing, many of thepractices this Guide discusses would also help a lawyer from being misused to facilitateterrorist financing.Money laundering involves three distinct stages: the placement stage, the layering stage,and the integration stage. The placement stage is the stage at which funds from illegalactivity, or funds intended to support illegal activity, are first introduced into thefinancial system. The layering stage involves further disguising and distancing the illicitfunds from their illegal source through the use of a series of parties and/or transactionsdesigned to conceal the source of the illicit funds. The integration phase of moneylaundering results in the illicit funds being considered “laundered” and integrated intothe financial system so that the criminal may expend “clean” funds. These stages areillustrated in the following diagram:2Sources of fundsTax crimes, fraud,embezzlement,drugs, theft, bribery,corruptionPlacementGoal:To deposit criminalproceeds into thefinancial systemCommon Methods: Change of currency Change ofdenomination Transportation ofcash Cash depositsFigure 1:stages of money laundering4LayeringGoal:Conceal the criminalorigin of proceedsCommon Methods: Wire transfers Withdrawals in cash Cash deposits inmultiple bankaccounts Split and mergeof various bankaccountsIntegrationUse of proceeds forpersonal benefitGoal:Create an apparentlegal origin forcriminal processesCommon Methods: Creating fictitiousloans, turnover,capital gains,contracts, financialstatements etc. Disguise ownershipof assets Use of criminalproceeds intransactions withthird partiesA Lawyer’s Guide to Detecting and Preventing Money Laundering

A. The 40 RecommendationsA diverse mix of domestic and international laws (both criminal and civil), regulationsand standards has been developed to counter money laundering and terrorist financing.Most significant among these are the Recommendations of the Financial Action TaskForce (“FATF”), an inter-governmental body established in 1989 at the G7 summit in Parisas a result of the growing concern over money laundering.3 The Recommendations arenot international laws, but are a set of internationally endorsed global standards, whichare based in part upon policies and recommendations stemming from United Nations(“UN”) conventions and Security Council resolutions. Further, the FATF Recommendationsrequire that individual countries formulate and implement offences of money launderingand terrorist financing in accordance with the provisions set out in the Recommendations;FATF members and certain other countries have formally agreed to implement theRecommendations.4The original Recommendations were drawn up in 1990 and were directed at the financialsector, as it was clear that banks were most at risk of being misused in connection withmoney laundering and terrorist financing. The Recommendations were first reviewed in1996 and were supplemented with the Eight Special Recommendations on TerroristFinancing in 2001.5 A further revision in 2003 expanded the reach of the Recommendationsto bodies that provide “access points” to financial systems, also referred to as “gatekeepers”.Broadly, these are persons, including lawyers6, FATF believes are in a position to identifyand prevent illicit money flows through the financial system by monitoring the conductof their clients and prospective clients and who could, if these persons are not vigilant,inadvertently facilitate money laundering and terrorist financing. The term used for“gatekeepers” in the 40 Recommendations is “Designated Non-Financial Businesses andProfessions” (“DNFBP”).7 Extending the reach of the Recommendations to capture DNFBPswas motivated by FATF’s perception that “gatekeepers” were unwittingly assistingorganised crime groups and other criminals to launder their funds by providing themwith advice, or acting as their financial intermediaries.8 Unfortunately, when theRecommendations were extended to gatekeepers scant accommodation was made for thefact that many of the gatekeepers (including lawyers) have a fundamental role andprovide different services as compared to the banks for which the Recommendationswere originally drafted. As a result, FATF’s approach treats all gatekeepers in the sameway as banks. Similarly, the extension was made without full recognition of the resourcesavailable to many gatekeepers, again particularly lawyers, as compared to the resourcesthat are available to many banks.The current version of the Recommendations, published in February 2012 and referredto in this Guide as the 40 Recommendations, embodies a focus on preventative measures,such as “customer due diligence” (“CDD”). This is done through the adoption of a riskbased approach, and the 40 Recommendations generally assume a somewhat differentAML approach to the “hard law” approach embodied in both past internationalconventions and criminalisation of money laundering activities. Controversially, theyinclude an obligation on gatekeepers, including lawyers, to report suspicious activity tothe authorities.I. Introduction and Background5

The Recommendations set out a framework of measures, rather than direct obligations,that countries should implement to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.The 2003 revisions to the Recommendations are absolutely key from a lawyer’sperspective. The 2003 revisions directed countries to bring into force laws or amendmentsto laws that put specific obligations on lawyers to take action in connection with moneylaundering and terrorist financing. Some in the legal profession view the Recommendations(and related national and regional legislation) as a source of another compliance burdenon a profession that is already heavily regulated and, with regard to the obligation toreport suspicious transactions, as a fundamental challenge to the lawyer-clientrelationship. Although lawyers and bar associations around the world (including the IBA,ABA and CCBE) deplore money laundering and terrorist financing and are keen to seelawyers play an appropriate role in the fight against these practices, many are concernedwith the way in which AML obligations have been placed on the profession and theimpact this has on lawyer-client relationships, a lawyer’s independence and role insociety and the rule of law. Notwithstanding these concerns, many jurisdictions havepassed laws that formally impose obligations on lawyers and some have provided thatbreach of these obligations can expose lawyers to criminal prosecution. Lawyers must beaware of these laws and, where applicable, need to comply with them.The basic intent behind the 40 Recommendations is consistent with what lawyers, asguardians of justice and the rule of law, and professionals subject to ethical obligations, havealways don

Money laundering involves three distinct stages: the placement stage, the layering stage, and the integration stage. The placement stage is the stage at which funds from illegal activity, or funds intended to support illegal activity, are first introduced into the financial system. The layering stage involves further disguising and distancing the illicit funds from their illegal source through .