Transcription

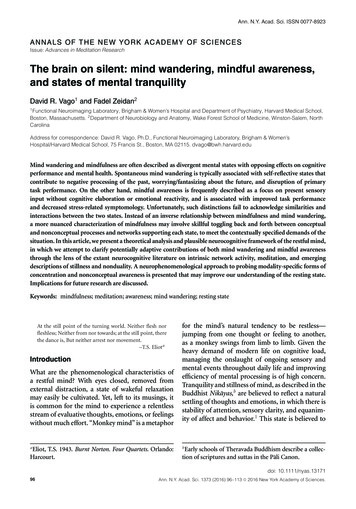

South African Journal of Childhood EducationISSN: (Online) 2223-7682, (Print) 2223-7674Page 1 of 9Review ArticleMindful awareness in early childhood educationAuthors:Suvi H. Nieminen1Nina Sajaniemi1Affiliations:1Department of TeacherEducation, University ofHelsinki, FinlandCorresponding author:Suvi : 11 Feb. 2016Accepted: 04 May 2016Published: 25 Aug. 2016How to cite this article:Nieminen, S.H. & Sajaniemi,N., 2016, ‘Mindful awarenessin early childhood education’,South African Journal ofChildhood Education 6(1),a399. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v6i1.399Copyright: 2016. The Authors.Licensee: AOSIS. This work islicensed under the CreativeCommons AttributionLicense.This study is a literature review, drawing mainly on the nine significant and good qualitystudies (i.e. published in peer-reviewed journals) that make up the evidence base for mindfulawareness practices in early childhood. Mindful awareness practices in this context means anindividual’s awareness of her own body and her inner emotions or tensions. Increasedawareness can decrease if individuals tend to impulsiveness or excessive stress. Self-regulationand mindful awareness skills are associated not only with stress regulation but also peerrelationships and social skills. This systematic review attempts to look at the research ofmindful awareness activities, programmes or interventions used as routine everyday activities.The second aim of this review is to examine the research design that has been used. The thirdaim of this study is to analyse the main themes and methods of these pieces of research.IntroductionChildren’s everyday life contains many events in which regulation skills are required. A widerange of desires, noise, transitions, large amounts of information and growing requirementsburden children’s stress systems. Their prefrontal neural connections – which take care ofappropriate regulation of stress – are still maturing, and children’s tolerance limits are narrowerthan those of adults (Sajaniemi et al. 2015). The developing brain is especially adaptable to theeffects of risk factors during the first 5 years of life (Shonkoff et al. 2009). Children’s inability toregulate stress jeopardises favourable advancements in social, emotional and cognitivedevelopment and increases the risk of social exclusion (Compas, Connor-Smith & Jaser 2004).Early childhood is a time of opportunity for interventions that reduce or moderate the effects ofstress exposures. Reducing the toxic stress of children and intervening early to improve preschoolpractices has the potential for improving the life course of children, families and future generations(DeSocio 2015).Constantly increasing (neuro)scientific research shows the benefits of training awareness,attention and calming skills, which have been shown to protect against the adverse effects ofstress (e.g. Siegel 2009). Studies of those programmes have demonstrated a range of cognitive,social and psychological benefits to school students (Meiklejohn et al. 2012). Mindful awarenesshas also been shown to alter brain functions, mental activity and interpersonal relationshipstowards well-being (Siegel 2009).Evidence for the benefits of mindful awareness training in adults has been shown in several reviewsand meta-analyses (Baer et al. 2006; Grossman et al. 2004; Irving, Dobkin & Park 2009; Salmon et al.2004). The interventions are usually delivered to adults in the form of mindfulness-based stressreduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, Lipworth & Burney 1985) or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy(MBCT; Segal, Williams & Teasdale 2002). However, in the published literature, there has beenscarce systematic evaluation of the effects of mindfulness training in children, particularly inpreschool children. This systematic literature review is the first to focus on a longitudinal,randomised control study of mindful awareness and/or mindfulness practices in early childhood.Mindful awareness, focused attention and self-regulationMuch of the interest in the applications of mindful awareness has been sparked by the introductionof Kabat-Zinn’s MBSR. Siegel (2009) defines mindfulness as follows:Read online:Scan this QRcode with yoursmart phone ormobile deviceto read online.mindfulness is actually not only a form of attention training (which many investigators studied it as). Andit is not only a form of affect regulation training (which some people were studying it as being as well).Maybe mindfulness is actually a relational process where you become your own best friend.Mindfulness appears to change how we see ourselves in the world; our experience of the selfchanges with mindfulness (Siegel 2009).http://www.sajce.co.zaOpen Access

Page 2 of 9Mindful awareness traits have been described by Baer et al.(2006) as including the propensity in life to (1) act withawareness; (2) be less reactive; (3) be non-judgemental; (4)develop the ability to label and describe with words theinternal world and (5) self-observe. Mindfulness is ‘anintegrative process that promotes well-being in body, mindand relationships’ (Siegel 2009).‘Mindful awareness’ contains attention focusing and includesbehaviours such as intense looking at objects or scenes, carefulexamining, fingering and inspecting them with interest fordetails (Ruff et al. 1990; Ruff & Rothbart 1996). Focusedattention is an effortful process of control because the childresists distractions, sustains attention and processes relevantinformation of the target in focus (Lawson & Ruff 2004).Attention has been generally associated with academicachievement outcomes (Duncan et al. 2007). Mindful awarenessskill is generally supposed to be a learned skill that enhancesself-management of attention (Baer 2003; Bishop et al. 2006;Borkovec et al. 2004; Kabat-Zinn 1994; Kumar, Feldman &Hayes 2008; Segal et al. 2002). The aim of mindful awarenesspractices is to enhance self-management of attention, topromote concentration, to increase emotional self-regulationand to develop social-emotional resiliency. The key componentis to practice mindful awareness throughout daily life, alwaysbeing aware of where attention is focused while engaged inroutine activities.Self-regulation contains the regulation of emotions,behaviours and cognitions (Bronson 2000). Early childhoodis the time when the child’s self-regulatory mechanismsevolve rapidly and lay the foundation for later development.Good self-regulation helps the child in challenging socialsituations, such as disputes and bullying. As children enterthe preschool period, they increasingly use effortful forms ofregulation developed through interactions with the caregiving environment (Posner & Rothbart 2009): the immaturebrain born into the world requires the more mature brainof the caregiver to allow its social, regulatory circuitryto develop (Siegel 2009). The infant uses social connectionsto develop regulatory ability. Even the smallest child canbe taught in ways that will help in difficult situations(Poikkeus 2011).Stress in early childhoodPhysiological responses to stress are well defined. Stressresponses include activation of a variety of hormone andneurochemical systems throughout the body. If the body failsto shut off the (stress hormone) cortisol release or experienceschronic stress, longer term effects can include suppression ofimmune functions and contributions to memory impairment,metabolic syndrome, bone mineral loss and muscle atrophy(Sapolsky, Romero & Munck 2000).Three distinct types of stress responses can be identified inyoung children: positive, tolerable and toxic. Positive stressresponse refers to a physiologic state that is brief and mild tohttp://www.sajce.co.zaReview Articlemoderate in magnitude (Shonkoff et al. 2009). Toxic stress inyoung children can lead to less outwardly visible yetpermanent changes in brain structure and function. Toxicstress can also result from strong, frequent or prolongedactivation of the body’s stress response systems (McEwen &Gianaros 2011; Shonkoff et al. 2009)Aim of this studyThis literature review contemplates the research of mindfulawareness programmes or interventions used in preschools.The first aim of this review is to analyse what kind of MAPprogrammes have been used with young children and thetheoretical backgrounds of these programmes. Another aimis to analyse the main themes and research design of previousstudies. There is also a focus on the disciplines and methodsof these pieces of research. The aim is to explore in particularany problems, contradictions or gaps in researching mindawareness practices.It was already known that this area has become an increasinglypopular subject to investigation in recent years. Definingand, in particular, measuring mind awareness skills and theirbenefits are still scientifically inconsistent and unsettled.Research needs to continue on early childhood interventionstargeted at improving sustained core skills, resiliency andcalming skills. Mindful awareness practices offer a promisingavenue for exploration.Previous literature overviews andsystematic literature reviewsLiterature overview and systematic literaturereviewA literature overview is an assessment of a body of researchthat addresses a research question. It is a ‘critical analysis of asegment of a published body of knowledge through summary,classification, and comparison of prior research studies,reviews of literature, and theoretical articles’ (University ofWisconsin Writing Center). The research questions are moregenerous than those in the systematic review.A systematic literature review aims to identify and thensummarise all relevant research evidence on a particularquestion, which fulfils certain criteria that are clearly describedat the outset, following a transparent research protocol:High-quality systematic reviews take great care to find allrelevant studies published and unpublished, asses each study,synthesize the findings from individual studies in an unbiasedway and present a balanced an impartial summary of thefindings with due consideration of any flaws in the evidence.(Davies & Crombie 2001)Two systematic literature reviews have been madeof mindfulness-based intervention (MBI) programmes forchildren aged 3–10 in 2005–2015 (Burke 2010; Zenner,Herrnleben-Kurz & Walach 2014). Three literature overviewswere found as well (Greenberg & Harris 2012; Rempel 2012;Weare 2013), and they are included in order to survey theOpen Access

Page 3 of 9Review Articleresearch field widely and with high-quality. Quantitativestatistical methods were used in only one of the systematicreviews (Zenner et al. 2014). This might be because of thephenomenon and the studies being ill-suited for this purpose.strategy designed to locate both published and unpublishedstudies. Twenty-four studies were identified, of which 13were published. In eight studies, mindfulness training wasimplemented at elementary school level, in grades 1–5.OverviewsConclusion of previous systematic literaturereviews and overviewsGreenberg and Harris (2012) present the current state ofresearch on contemplative practices with children and youth,but their review does not meet the criteria of a systematicliterature review. The programmes the researchers foundvaried widely from single sessions to daily practice overweeks or months. Greenberg and Harris suggest that repetitionand practice may play a key role in interventions to alterneural activity and create healthy habits of mind and body.With sustained practice, these habits may become routine atneural or mental levels to subsequently regulate behaviourin relatively automatic ways. Greenberg and Harris suggestlonger term follow-up lasting at least 6 months. Active controlgroups could help to further differentiate the key componentsof interventions.Rempel (2012) made a review of literature with an argumentfor school-based implementation. According to Rempel, it isimportant to develop assessment tools specifically forchildren and test their reliability and validity. Rempelmentions that the only measure for mindfulness skills thathas been normed and adapted for use with children is theChild and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (Thompson &Gauntlett-Gilbert 2008). According to Rempel, researchersalso suggest that teachers of mindfulness-based activitiesshould have a regular, personal and mindfulness-basedpractice in order to speak with any authority and answerquestions posed by students.Weare (2013) reports on 20 or so significant studies inmindfulness-based programmes that deserve seriousattention to widen and deepen the growing evidence base.Weare points out variation in the quality of studies as areason for not making a systematic review. She also pointsout typical methodological problems in the studies, such assmall numbers of participants, little use of control groupsand random allocation of participants, no standardisedmeasures, plenty of reliance on self-reporting and participantswho volunteer rather than being chosen.Systematic reviewsBurke (2009) is interested in MBSR and MBCT models. MBSRand MBCT are defined as experiential learning programmesthat include weekly group sessions, regular home practiceand a core curriculum of formal and informal mindfulnesspractices like body scan and sitting, movement and walkingmeditations and bringing mindful awareness to dailyactivities. Fifteen studies meeting these terms were locatedand reviewed.Zenner, Herrnleben-Kurz and Walach (2014) systematicallyreviewed the effects of school-based mindfulness interventionson psychological outcomes, using a comprehensive searchhttp://www.sajce.co.zaAll the authors of these reviews find conclusive evidence thatmindfulness-based practices benefit children and youngpeople. The practices can be effective on a wide-range ofoutcomes, such as intellectual skills, improving sustainedattention, visual-spatial memory, working memory andconcentration, even physical health. What might be the bestpractice with preschool children? The studies point out thatteaching mindfulness-based technique to children and youngpeople has to be rather different to teaching them to adults,that is methods, materials and activities are generally moreplayful and convivial, with a focus on fun, and with shorterperiods of silence.In measuring outcomes, the researchers should not rely onlyon self-reported data and questionnaires in general; studiesshould use a mixed-methods approach to assess outcomeand acceptability, adopting methods such as review sessions,teacher reports and individual interviews, observations oftraining sessions and student questionnaires and interviews.Some researchers point out long-term (at least 6 months)follow-up assessments to be important in determiningwhether the benefits of mindfulness training are sustainedover time. Also, the amount of time spent in mindfulnesspractice might affect outcomes. All the studies emphasiseactive control groups, repetition and practice, large numbersof participants, active control groups, random allocation ofparticipants (not only volunteers) and standardised, ageappropriate measures.MethodsIn this study, Fink’s (2005:3) definition of a research literaturereview is adapted as the operative definition of a systematicliterature review.Search criteriaSearch in a systematic review works best when its aims andresearch questions are clearly established and demarcated. Inthis study, the research questions were delimited andspecified on the basis of the target group, intervention,outcome and survey design factors.This systematic literature search was targeted at researchaimed at longitudinal intervention and research carried outon mindful awareness practices programmes for children.The original aim was to chart programmes for children aged3–6 years, but no studies in this age group were found.Thus, the age range had to be set at 3–10 years. Interest wasfocused on these programmes’ impacts on children’s socialskills, self-regulation skills, school readiness skills andgroup dynamics.Open Access

Only the original articles were accepted in this review. Asmeditation and yoga are normative parts of Hindu cultureand could have religious connotations for some people, it ispossible that they arouse prejudices in other cultural settings.Thus, interventions consisting mainly of religious elementsof some kind were decided to be excluded.IDENTIFICATIONSCREENINGThe systematic literature search was carried out using Ebsco,Web Of Science, Scopus, ERIC, PubMed and PsycINFO databases.Later, these outcomes were completed using the Google Scholarsearch mode. English language articles published between2005 and 2015 in peer-reviewed journals were reviewed,assuming that sufficiently high-quality studies made in theseyears could be found. Search terms included ‘mindfulnessbased’, ‘mindful awareness’, ‘interventions’, ‘children’ and‘preschool’. In the first search, 74 studies were located, and1090 with Google Scholar. A large proportion of the articleswere the same in various searches.Records identifiedthrough databasesearching(n 74 )ELIGIBILITYAt the beginning, a search of studies was carried out manually(manual systematic literature search) and supplementedlater by references of other (systematic) reviews and metaanalyses (Burke 2005; Rempel 2012; Zenner et al. 2014) foundusing the Related Articles search mode.Review ArticleINCLUDEDPage 4 of 9Additional recordsidentified through GoogleScholar and references(n 1090 )Records screened(n 1164)Records excludedbased on titles(n 1118 )Records screened(n 26 )Records excludedbased on abstracts(n 9)Full-text articles assessedfor eligibility(n 17 )Full-text articleexcluded,(n 8)Studies included inqualitative synthesis(n 9)Source: Nieminen 2016FIGURE 1: Flow diagram for the systematic review of mindful awarenesspractices programmes for children aged 3–10, 2005–2015.been used with young children, so other kinds of studieswere excluded. The following sections describe the studiesapproved in the literature in chronological order, fromprevious to the most recent.Studies were selected if the following criteria were met:1. Interventions were mindful awareness or mindfulnessbased.2. Interventions that consist mainly of religious elementswere excluded.3. Participants were 3- to 10-year-old children in an educationalcontext.Search implementation and resultsThe retrieved articles were assessed initially on the basis ofthe summaries. Most of the studies were excluded becausethe intervention was implemented in a setting other thanregular school life.(Pre-)School-based programmes for 3- to 10-year-old childrenand based on mindfulness or mindful awareness skills wereinvestigated, and studies and programmes with no religiouselements were picked for further assessment. The summariesof nine studies met the criteria. The entire articles were readthrough, and all of them were adopted in the final researchliterature review.Studies that did not meet the criteria of the research design butwere remarkable and interesting per se were categorised asgeneral and used later as background material of this review.Previous literature reviews and meta-analyses were also usedto describe and give background to the phenomenon (Figure 1).Approved studiesStudies considering mind awareness or mindfulness skills inchildhood have mainly been intervention studies. In thisreview, the aim is to analyse what kind of interventions hashttp://www.sajce.co.zaNapoli, Krech and Holley (2005) report on a project, whichintegrated mindfulness and relaxation work with 228children aged 5–8. The project included twelve 45-minutesessions of mindfulness and relaxation, designed andintended to help students learn to focus and pay attention.The 24-week training contained exercises like breathing,body scan, movement and sensory motor awarenessactivities. The teachers were external and were veryconversant: they have been professionally trained asmindfulness training instructors and have facilitatedmindfulness for years. The main research question waswhether participation in a mindfulness training programme(Attention Academy Programme [AAP]) affected students’outcomes on measures of attention.Students were chosen at random to be placed either in theexperimental group or control group. A total of 194 studentscompleted the programme. One moment of training includedbreathing exercises, a body scan visualisation application, abody movement–based task and a post-session de-briefing orsharing of instructor feedback with the class. Results showedsignificant differences between those who did and did notparticipate in the AAP training.Semple, Reid and Miller (2005) delivered a modified andmanualised MBCT course taught by trained, experiencedmindfulness teachers in a school-based setting. The courselasted 6 weeks, for 45 minutes a week. The participants were5 children aged 7–9 years and suffering from anxiety in anurban elementary school. Techniques were adapted from twoadult programmes, MBSR and MBCT. Participants were alsoencouraged to discover their own ways to practiceOpen Access

Page 5 of 9mindfulness at home. Some improvements were reported forall the children in at least one area (academic functioning,internalising/externalising problems).Schonert-Reichl and Lawlor (2010) in their earlier researchconducted a study of 12 elementary classrooms, wherestudents were aged 9–14. Six classrooms were randomisedto receive the programme and six to waitlist control. Theintervention included 10 lessons and 3 times daily practiceof mindfulness meditation, including quieting the mind andfocusing on breathing, mindful attention, managing negativeemotions and negative thinking and acknowledgment of theself and others. The main research question was whetherparticipation in a mindfulness training programme(Mindfulness Education [ME]) affected students’ optimism,self-concept, positive affect and social-emotional functioningin school. The findings show that students exposed to the MEprogramme evidenced significant improvements in socialand emotional competence: Attention and Concentration,and Social Emotional Competence.Flook et al. (2010) report on a randomised control study of 64children aged 7–9 years. The programme contained classicalmindfulness training with age-appropriate exercises andgames. Each class session took 30 minutes; they weredelivered twice per week, for 8 weeks, and contained sittingmeditation, body scan, exercises, and activities and games,which involve interactions among students and betweenstudents and the instructor. The purpose of the study was toevaluate whether participation in the programme has impactson children’s executive functions (EF) processes areneurocognitive processes like inhibition, set shifting, workingmemory, planning and fluency; Willcut et al. 2005). Thefindings reveal improvements in behavioural regulation,meta-cognition, overall EF.Mendelson et al. (2010) delivered a pilot randomisedcontrolled trial for 97 participants aged 9–10. The interventiondeveloped in Holistic Life Foundation (HLF) combined amindfulness and yoga programme. These interventionsessions were taught by an external instructor and scheduledduring a period in which students engage in non-academicactivities. Children’s social, emotional and behaviouraloutcomes were assessed at baseline and immediately afterthe intervention by self-report checklists. Students wereencouraged to practice the skills outside class as well. As aresult, the programme had a positive impact on problematicresponses to stress including rumination, intrusive thoughtsand emotional arousal.Van de Weijer-Bergsma et al. (2012) report on a research of8- to 12-year-old children from three elementary schools,where classes were randomised to an intervention group ora control group. External trainers delivered 12 30-minutesessions in 6 weeks (two sessions per week). During sessions,children participate in secular and age-appropriatemeditation practices focusing on non-judging awareness ofsounds, bodily sensations, breathing, thoughts and emotions.http://www.sajce.co.zaReview ArticleChildren were also encouraged to practice mindfulness athome. The results showed the Mindful Kids-programme toreduce stress and stress-related mental health and behaviouralproblems.Klatt et al. (2013) delivered a programme that can be definedas MBI for elementary school-aged children combiningmusic, yoga and written and visual arts. The researchersused the theory of Appreciative Inquiry as well forencouraging participants to ask questions and toacknowledge their positive skills, support systems orcoping mechanisms that are already present in their life.Move-Into-Learning was of 8-weeks duration, with one45-minute session a week. Sessions with 8-year-oldparticipants were delivered by an external trainer and theclass teacher. The results showed decreases in students disruptive behaviours, like an attention-deficit or attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) index and incognitive/inattentive behaviour.Black and Fernando (2014) report on a 5-week mindfulnessbased curriculum (Mindful Schools K-5 grade curriculum,[MS]) in a lower-income and ethnic minority elementaryschool, from kindergarten through sixth grade. Thecurriculum was delivered by two external mindfulnessmeditation teachers in 15-minute sessions, 3 times per weekfor 5 weeks. All classrooms were randomly assigned toreceive the MS curriculum or MS plus additionally as once-aweek classes (MS ). As a result, the children were reportedlyimproved at paying attention, calming and self-control,participation in activities and caring/respect for others.Schonert-Reichl et al. (2015) delivered an intervention calledMind UP programme in their research. It is a mindfulnessbased SEL programme that consists of 12 lessons (taught byclass teacher) once-a-week, with each lesson lasting 40–50minutes. The programme contains 3-minute core mindfulnesspractice with focusing on breathing and attentive listening toa single resonant sound. The core programme was done threetimes a day, every day. Participants were aged 9–10 andtotalled 99. Teachers were encouraged to generalise thecurriculum-based skills throughout the school day. In thisrandomised controlled trial study, a control group was used,which received a ‘business as usual’ social responsibilityprogramme. The purpose of the study was to examinewhether the Mind UP programme would lead toimprovements in EFs, stress regulation, social-emotionalcompetence and school achievement (Table 1).Taxonomy of resultsStudy designs and materials in the intervention studies didnot differ significantly from each other. In assessing studies,particular attention should be paid to their methodologicalmerit: definitions, methods, variables, durations and samplesizes. In this study, the theoretical framework, measurements,intervention components, duration times and interventionfeatures are reviewed as well (see Table 2).Open Access

Page 6 of 9Review ArticleTABLE 1: Mindfulness-based interventions with earchdesignTreatment groupControl groupRandomassignmentKey wordsSchonert-Reichl et al.(2015)999–10Elementaryschool Canada4095–10Elementaryschool USABusiness as usualsocial responsibilityprogrammeNoKlatt et al. (2013)418–9Elementaryschool USANoNoVan de Weijer-Bergsmaet al. (2012)2088–12Waitlist xperimentalstudySocial and emotional learning,well-being, mindfulness,intervention, pro-socialityMindfulness, meditation, children,teachers, ethnically diverse,school-basedResiliency, coping skills, behaviouralimpact, mindfulness-basedinterventions, appreciative inquiry,creative arts–based activitiesMindfulness, attention training,elementary school, children, stressSchonert-Reichl andLawlor (2010)Elementaryschool TheNetherlandsElementaryschool CanadaWaitlist controlNoMindfulness, adolescents,prevention, optimism, socialcompetenceFlook et al. (2010)647–9Elementaryschool USARandomisedcontrolledtrialMindUP, 1/week 40–50minutes, core practice3/day over 4 monthsMindful Schools (MS)3/week 15 minutesover 5 weekMove-Into-Learning(MIL) 1/week45 minutes over8 weeksMindfulKids 2/week30 minutes over6 weeksMindfulnessEducation (ME) 1/week40–50 minutes corepractice 3/day over10 weeksAge-appropriateMAPs, 2/week over8 weeksYesBlack and Fernando(2014)RandomisedcontrolledtrialPre-test topost-testgroupPre-test topost-testgroupQuiet activities(like silent esNapoli et al. (2005)1946–8Elementaryschool USASemple et al. (2005)57–8Elementaryschool USAResearchTreatment groupdesignRandomised Holistic Life Foundationcontrolled trial programme (HLF)4/week 45 minutesover 12 weeksRandomised Attention AcademycontrolledProgramme (AAP)trial45 minutes 2/monthover 24 weeksOpen clinical Mindfulness trainingtrialMACK CLUBage-appropriate45 min 1/week over6 weeksControl groupMendelson et al. (2010)ParticipantdescriptionElementaryschools USAEducation, intervention,mindfulness, executive control,meta-cognition, behaviouralregulationKey wordsWaitlist controlNoMindfulness, yoga, prevention,school-based intervention, chronicstressQuiet activities(like silent reading)YesStress, attention, wellness,curriculum, mindfulnessNoNoAttention, anxiety, children, cognitivetherapy, group treatment,psychotherapy, meditation,mindfulness, mindfulness-basedcognitive therapy, stressSource: Nieminen 2016TABLE 2: General features of the studies.StudyTheoretical frameworkIntervention componentsMeasuresDuration weeks/hoursIntervention featuresSchonert-Reichlet al. (2015)Positive psychology(including SEL)Presentation programme byNeurobehavioral Systems,Saliva test, Interpersonal ReactivityIndex (IRI), Resiliency Inventory (RI),Self-Description Questionnaire(SDQ), Seattle PersonalityQuestionnaire for Children, MindfulAttention Awareness Scale, SocialGoals Questionnaire.4 months( 17 weeks)28 hoursClass by teacherBlack and Fernando(20

The aim of mindful awareness practices is to enhance self-management of attention, to promote concentration, to increase emotional self-regulation and to develop social-emotional resiliency. The key component is to practice mindful awareness throughout daily life, always being aware of where