Transcription

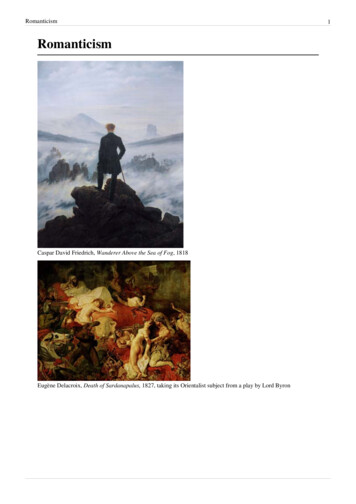

RomanticismRomanticismCaspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818Eugène Delacroix, Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, taking its Orientalist subject from a play by Lord Byron1

RomanticismPhilipp Otto Runge, The Morning, 1808Romanticism (also the Romantic era or the Romantic period) was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movementthat originated in Europe toward the end of the 18th century and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate[1]period from 1800 to 1850. Partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, it was also a revolt against aristocraticsocial and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment and a reaction against the scientific rationalization of nature.[]It was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature, but had a major impact on historiography,[2]education[3] and the natural sciences.[4] Its effect on politics was considerable and complex; while for much of thepeak Romantic period it was associated with liberalism and radicalism, in the long term its effect on the growth ofnationalism was probably more significant.The movement validated strong emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis onsuch emotions as apprehension, horror and terror, and awe—especially that which is experienced in confronting thesublimity of untamed nature and its picturesque qualities, both new aesthetic categories. It elevated folk art andancient custom to something noble, made spontaneity a desirable characteristic (as in the musical impromptu), andargued for a "natural" epistemology of human activities as conditioned by nature in the form of language andcustomary usage. Romanticism reached beyond the rational and Classicist ideal models to elevate a revivedmedievalism and elements of art and narrative perceived to be authentically medieval in an attempt to escape theconfines of population growth, urban sprawl, and industrialism, and it also attempted to embrace the exotic,unfamiliar, and distant in modes more authentic than Rococo chinoiserie, harnessing the power of the imagination toenvision and to escape.Although the movement was rooted in the German Sturm und Drang movement, which prized intuition and emotionover Enlightenment rationalism, the ideologies and events of the French Revolution laid the background from whichboth Romanticism and the Counter-Enlightenment emerged. The confines of the Industrial Revolution also had theirinfluence on Romanticism, which was in part an escape from modern realities; indeed, in the second half of the 19thcentury, "Realism" was offered as a polarized opposite to Romanticism.[5] Romanticism elevated the achievementsof what it perceived as heroic individualists and artists, whose pioneering examples would elevate society. It alsolegitimized the individual imagination as a critical authority, which permitted freedom from classical notions of form2

Romanticism3in art. There was a strong recourse to historical and natural inevitability, a Zeitgeist, in the representation of its ideas.Defining RomanticismBasic characteristicsDefining the nature of Romanticism may be approached from the starting point of the primary importance of the freeexpression of the feelings of the artist. The importance the Romantics placed on untrammelled feeling is summed upin the remark of the German painter Caspar David Friedrich that "the artist's feeling is his law".[6] To WilliamWordsworth poetry should be "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings".[7] In order to truly express thesefeelings, the content of the art must come from the imagination of the artist, with as little interference as possiblefrom "artificial" rules dictating what a work should consist of. Coleridge was not alone in believing that there werenatural laws governing these matters which the imagination, at least of a good creative artist, would freely andunconsciously follow through artistic inspiration if left alone to do so.[8] As well as rules, the influence of modelsfrom other works would impede the creator's own imagination, so originality was absolutely essential. The conceptof the genius, or artist who was able to produce his own original work through this process of "creation fromnothingness", is key to Romanticism, and to be derivative was the worst sin.[9][10][11][12] This idea is often called"romantic originality."[13]Not essential to Romanticism, but so widespread as to be normative,was a strong belief and interest in the importance of nature. Howeverthis is particularly in the effect of nature upon the artist when he issurrounded by it, preferably alone. In contrast to the usually very socialart of the Enlightenment, Romantics were distrustful of the humanworld, and tended to believe that a close connection with nature wasmentally and morally healthy. Romantic art addressed its audiencesdirectly and personally with what was intended to be felt as thepersonal voice of the artist. So, in literature, "much of romantic poetryinvited the reader to identify the protagonists with the poetsthemselves".[14]William Blake, The Little Girl Found, fromSongs of Innocence and Experience, 1794According to Isaiah Berlin, Romanticism embodied "a new and restlessspirit, seeking violently to burst through old and cramping forms, anervous preoccupation with perpetually changing inner states ofconsciousness, a longing for the unbounded and the indefinable, forperpetual movement and change, an effort to return to the forgottensources of life, a passionate effort at self-assertion both individual andcollective, a search after means of expressing an unappeasableyearning for unattainable goals."[15]The termThe group of words with the root "Roman" in the various European languages, such as romance and Romanesque,has a complicated history, but by the middle of the 18th century "romantic" in English and romantique in Frenchwere both in common use as adjectives of praise for natural phenomena such as views and sunsets, in a sense closeto modern English usage but without the implied sexual element. The application of the term to literature firstbecame common in Germany, where the circle around the Schlegel brothers, critics August and Friedrich, began tospeak of romantische Poesie ("romantic poetry") in the 1790s, contrasting it with "classic" but in terms of spirit

Romanticismrather than merely dating. Friedrich Schlegel wrote in his Dialogue on Poetry (1800), "I seek and find the romanticamong the older moderns, in Shakespeare, in Cervantes, in Italian poetry, in that age of chivalry, love and fable,from which the phenomenon and the word itself are derived."[16] In both French and German the closeness of theadjective to roman, meaning the fairly new literary form of the novel, had some effect on the sense of the word inthose languages. The use of the word did not become general very quickly, and was probably spread more widely inFrance by its persistent use by Madame de Staël in her De L'Allemagne (1813), recounting her travels inGermany.[17] In England Wordsworth wrote in a preface to his poems of 1815 of the "romantic harp" and "classiclyre",[17] but in 1820 Byron could still write, perhaps slightly disingenuously, "I perceive that in Germany, as well asin Italy, there is a great struggle about what they call "Classical" and "Romantic", terms which were not subjects ofclassification in England, at least when I left it four or five years ago".[18] It is only from the 1820s that Romanticismcertainly knew itself by its name, and in 1824 the Académie française took the wholly ineffective step of issuing adecree condemning it in literature.[19]The periodUnsurprisingly, given its rejection on principle of rules, Romanticism is not easily defined, and the period typicallycalled Romantic varies greatly between different countries and different artistic media or areas of thought. MargaretDrabble described it in literature as taking place "roughly between 1770 and 1848",[20] and few dates much earlierthan 1770 will be found. In English literature, M. H. Abrams placed it between 1789, or 1798, this latter a verytypical view, and about 1830, perhaps a little later than some other critics.[21] In other fields and other countries theperiod denominated as Romantic can be considerably different; musical Romanticism, for example, is generallyregarded as only having ceased as a major artistic force as late as 1910, but in an extreme extension the Four LastSongs of Richard Strauss are described stylistically as "Late Romantic" and were composed in 1946–48.[22] Howeverin most fields the Romantic Period is said to be over by about 1850, or earlier.The early period of the Romantic Era was a time of war, with the French Revolution (1789–1799) followed by theNapoleonic Wars until 1815. These wars, along with the political and social turmoil that went along with them,served as the background for Romanticism.[23] The key generation of French Romantics born between 1795–1805had, in the words of one of their number, Alfred de Vigny, been "conceived between battles, attended school to therolling of drums".[24]Context and place in historyThe more precise characterization and specific definition of Romanticism has been the subject of debate in the fieldsof intellectual history and literary history throughout the 20th century, without any great measure of consensusemerging. That it was part of the Counter-Enlightenment, a reaction against the Age of Enlightenment, is generallyaccepted. Its relationship to the French Revolution which began in 1789 in the very early stages of the period, isclearly important, but highly variable depending on geography and individual reactions. Most Romantics can be saidto be broadly progressive in their views, but a considerable number always had, or developed, a wide range ofconservative views,[25] and nationalism was in many countries strongly associated with Romanticism, as discussed indetail below.In philosophy and the history of ideas, Romanticism was seen by Isaiah Berlin as disrupting for over a century theclassic Western traditions of rationality and the very idea of moral absolutes and agreed values, leading "tosomething like the melting away of the very notion of objective truth",[26] and hence not only to nationalism, but alsofascism and totalitarianism, with a gradual recovery coming only after the catharsis of World War II.[27] For theRomantics, Berlin says,in the realm of ethics, politics, aesthetics it was the authenticity and sincerity of the pursuit of innergoals that mattered; this applied equally to individuals and groups — states, nations, movements. This ismost evident in the aesthetics of romanticism, where the notion of eternal models, a Platonic vision of4

Romanticism5ideal beauty, which the artist seeks to convey, however imperfectly, on canvas or in sound, is replacedby a passionate belief in spiritual freedom, individual creativity. The painter, the poet, the composer donot hold up a mirror to nature, however ideal, but invent; they do not imitate (the doctrine of mimesis),but create not merely the means but the goals that they pursue; these goals represent the self-expressionof the artist's own unique, inner vision, to set aside which in response to the demands of some "external"voice — church, state, public opinion, family friends, arbiters of taste — is an act of betrayal of whatalone justifies their existence for those who are in any sense creative.[28]John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott,1888, after a poem by Tennyson; like manyVictorian paintings, romantic but not Romantic.Arthur Lovejoy attempted to demonstrate the difficulty of definingRomanticism in his seminal article "On The Discrimination ofRomanticisms" in his Essays in the History of Ideas (1948); somescholars see Romanticism as essentially continuous with the present,some like Robert Hughes see in it the inaugural moment ofmodernity,[29] and some like Chateaubriand, 'Novalis' and SamuelTaylor Coleridge see it as the beginning of a tradition of resistance toEnlightenment rationalism—a 'Counter-Enlightenment'— [30][31] to beassociated most closely with German Romanticism. An earlierdefinition comes from Charles Baudelaire: "Romanticism is preciselysituated neither in choice of subject nor exact truth, but in the way offeeling."[32]The end of the Romantic era is marked in some areas by a new style of Realism, which affected literature, especiallythe novel and drama, painting, and even music, through Verismo opera. This movement was led by France, withBalzac and Flaubert in literature and Courbet in painting; Stendhal and Goya were important precursors of Realismin their respective media. However, Romantic styles, now often representing the established and safe style againstwhich Realists rebelled, continued to flourish in many fields for the rest of the century and beyond. In music suchworks from after about 1850 are referred to by some writers as "Late Romantic" and by others as "Neoromantic" or"Postromantic", but other fields do not usually use these terms; in English literature and painting the convenient term"Victorian" avoids having to characterise the period further.In northern Europe, the Early Romantic visionary optimism and belief that the world was in the process of greatchange and improvement had largely vanished, and some art became more conventionally political and polemical asits creators engaged polemically with the world as it was. Elsewhere, including in very different ways the UnitedStates and Russia, feelings that great change was underway or just about to come were still possible. Displays ofintense emotion in art remained prominent, as did the exotic and historical settings pioneered by the Romantics, butexperimentation with form and technique was generally reduced, often replaced with meticulous technique, as in thepoems of Tennyson or many paintings. If not realist, late 19th-century art was often extremely detailed, and pridewas taken in adding authentic details in a way that earlier Romantics did not trouble with. Many Romantic ideasabout the nature and purpose of art, above all the pre-eminent importance of originality, continued to be importantfor later generations, and often underlie modern views, despite opposition from theorists.

Romanticism6Romantic literatureIn literature, Romanticism found recurrentthemes in the evocation or criticism of the past,the cult of "sensibility" with its emphasis onwomen and children, the heroic isolation of theartist or narrator, and respect for a new, wilder,untrammeled and "pure" nature. Furthermore,several romantic authors, such as Edgar AllanPoe and Nathaniel Hawthorne, based theirwritings on the supernatural/occult and humanpsychology. Romanticism tended to regard satireas something unworthy of serious attention, aprejudice still influential today.[33]Henry Wallis, The Death of Chatterton 1856, by suicide at 18 in 1770.The precursors of Romanticism in Englishpoetry go back to the middle of the 18th century,including figures such as Joseph Warton (headmaster at Winchester College) and his brother Thomas Warton,professor of Poetry at Oxford University.[34] Joseph maintained that invention and imagination were the chiefqualities of a poet. Thomas Chatterton is generally considered to be the first Romantic poet in English.[35] TheScottish poet James Macpherson influenced the early development of Romanticism with the international success ofhis Ossian cycle of poems published in 1762, inspiring both Goethe and the young Walter Scott. Both Chatterton andMacpherson's work involved elements of fraud, as what they claimed to be earlier literature that they had discoveredor compiled was in fact entirely their own work. The Gothic novel, beginning with Horace Walpole's The Castle ofOtranto (1764), was an important precursor of one strain of Romanticism, with a delight in horror and threat, andexotic picturesque settings, matched in Walpole's case by his role in the early revival of Gothic architecture. TristramShandy, a novel by Laurence Sterne (1759–67) introduced a whimsical version of the anti-rational sentimental novelto the English literary public.GermanyAn early German influence came from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe,whose 1774 novel The Sorrows of Young Werther had young menthroughout Europe emulating its protagonist, a young artist with a verysensitive and passionate temperament. At that time Germany was amultitude of small separate states, and Goethe's works would have aseminal influence in developing a unifying sense of nationalism.Another philosophic influence came from the German idealism ofJohann Gottlieb Fichte and Friedrich Schelling, making Jena (whereFichte lived, as well as Schelling, Hegel, Schiller and the brothersSchlegel) a center for early German Romanticism ("Jenaer Romantik").Title page of Volume III of Des KnabenImportant writers were Ludwig Tieck, Novalis (Heinrich vonWunderhorn, 1808Ofterdingen, 1799), Heinrich von Kleist and Friedrich Hölderlin.Heidelberg later became a center of German Romanticism, wherewriters and poets such as Clemens Brentano, Achim von Arnim, and Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff met regularlyin literary circles.Important motifs in German Romanticism are travelling, nature, and Germanic myths. The later GermanRomanticism of, for example, E. T. A. Hoffmann's Der Sandmann (The Sandman), 1817, and Joseph Freiherr von

Romanticism7Eichendorff's Das Marmorbild (The Marble Statue), 1819, was darker in its motifs and has gothic elements. Thesignificance to Romanticism of childhood innocence, the importance of imagination, and racial theories all combinedto give an unprecedented importance to folk literature, non-classical mythology and children's literature, above all inGermany. Brentano and von Arnim were significant literary figures who together published Des KnabenWunderhorn ("The Boy's Magic Horn" or cornucopia), a collection of versified folk tales, in 1806–08. The firstcollection of Grimms' Fairy Tales by the Brothers Grimm was published in 1812.[36] Unlike the much later work ofHans Christian Andersen, who was publishing his invented tales in Danish from 1835, these German works were atleast mainly based on collected folk tales, and the Grimms remained true to the style of the telling in their earlyeditions, though later rewriting some parts. One of the brothers, Jacob, published in 1835 Deutsche Mythologie, along academic work on Germanic mythology.[37] Another strain is exemplified by Schiller's highly emotionallanguage and the depiction of physical violence in his play The Robbers of 1781.English literatureIn English literature, the group of poets nowconsidered the key figures of the Romantic movementincludes William Wordsworth, Samuel TaylorColeridge, John Keats, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley,Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the much older WilliamBlake, followed later by the isolated figure of JohnClare. The publication in 1798 of Lyrical Ballads,with many of the finest poems by Wordsworth andColeridge, is often held to mark the start of themovement. The majority of the poems were byWordsworth, and many dealt with the lives of thepoor in his native Lake District, or the poet's feelingsabout nature, which were to be more fully developedin his long poem The Prelude, never published in hislifetime. The longest poem in the volume wasColeridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner whichshowed the Gothic side of English Romanticism, andthe exotic settings that many works featured. In theperiod when they were writing the Lake Poets werewidely regarded as a marginal group of radicals,though they were supported by the critic and writerWilliam Hazlitt and others.Byron c. 1816, by Henry Harlow

RomanticismIn contrast Lord Byron and Walter Scott achievedenormous fame and influence throughout Europewith works exploiting the violence and drama of theirexotic and historical settings; Goethe called Byron"undoubtedly the greatest genius of our century".[38]Scott achieved immediate success with his longnarrative poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel in 1805,followed by the full epic poem Marmion in 1808.Both were set in the distant Scottish past, alreadyevoked in Ossian; Romanticism and Scotland were tohave a long and fruitfiul partnership. Byron hadequal success with the first part of Childe Harold'sPilgrimage in 1812, followed by four "Turkish tales",all in the form of long poems, starting with TheGiaour in 1813, drawing from his Grand Tour whichhad reached Ottoman Europe, and orientalizing thethemes of the Gothic novel in verse. These featureddifferent variations of the "Byronic hero", and hisown life contributed a further version. Scottmeanwhile was effectively inventing the historicalnovel, beginning in 1814 with Waverley, set in theGirodet, Chateaubriand in Rome, 18081745 Jacobite Rising, which was an enormous andhighly profitable success, followed by over 20 further Waverley Novels over the next 17 years, with settings goingback to the Crusades that he had researched to a degree that was new in literature.[39]In contrast to Germany, Romanticism in English literature had little connection with nationalism, and the Romanticswere often regarded with suspicion for the sympathy many felt for the ideals of the French Revolution, whosecollapse and replacement with the dictatorship of Napoleon was, as elsewhere in Europe, a shock to the movement.Though his novels celebrated Scottish identity and history, Scott was politically a firm Unionist. Several spent muchtime abroad, and a famous stay on Lake Geneva with Byron and Shelley in 1816 produced the hugely influentialnovel Frankenstein by Shelley's wife-to-be Mary Shelley and the novella The Vampyre by Byron's doctor JohnWilliam Polidori. The lyrics of Robert Burns in Scotland and Thomas Moore, from Ireland but based in London orelsewhere reflected in different ways their countries and the Romantic interest in folk literature, but neither had afully Romantic approach to life or their work.Though they have modern critical champions such as Georg Lukács, Scott's novels are today more likely to beexperienced in the form of the many operas that continued to be based on them over the following decades, such asDonizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor and Vincenzo Bellini's I puritani (both 1835). Byron is now most highly regardedfor his short lyrics and his generally unromantic prose writings, especially his letters, and his unfinished satire DonJuan.[40] Unlike many Romantics, Byron's widely-publicised personal life appeared to match his work, and his deathat 36 in 1824 from disease when helping the Greek War of Independence appeared from a distance to be a suitablyRomantic end, entrenching his legend.[41] Keats in 1821 and Shelley in 1822 both died in Italy, Blake (at almost 70)in 1827, and Coleridge largely ceased to write in the 1820s. Wordsworth was by 1820 respectable andhighly-regarded, holding a government sinecure, but wrote relatively little. In the discussion of English literature, theRomantic period is often regarded as finishing around the 1820s, or sometimes even earlier, although many authorsof the succeeding decades were no less committed to Romantic values.The most significant novelist in English during the peak Romantic period, other than Walter Scott, was Jane Austen,whose essentially conservative world-view had little in common with her Romantic contemporaries, retaining a8

Romanticismstrong belief in decorum and social rules, though critics have detected tremors under the surface of some works,especially Mansfield Park (1814) and Persuasion (1817).[42] But around the mid-century the undoubtedly Romanticnovels of the Yorkshire-based Brontë family appeared, in particular Charlotte's Jane Eyre and Emily's WutheringHeights, which were both published in 1847.Byron, Keats and Shelley all wrote for the stage, but with little success in England, with Shelley's The Cenci perhapsthe best work produced, though that was not played in a public theatre in England until a century after his death.Byron's plays, along with dramatisations of his poems and Scott's novels, were much more popular on the Continent,and especially in France, and through these versions several were turned into operas, many still performed today. Ifcontemporary poets had little success on the stage, the period was a legendary one for performances of Shakespeare,and went some way to restoring his original texts and removing the Augustan "improvements" to them. The greatestactor of the period, Edmund Kean, restored the tragic ending to King Lear;[43] Coleridge said that, “Seeing him actwas like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning.”[44]FranceRomanticism was relatively late in developing in French literature, even more so than in the visual arts. The 18thcentury precursor to Romanticism, the cult of sensibility, had become associated with the Ancien regime, and theFrench Revolution had been more of an inspiration to foreign writers than those experiencing it at first hand. Thefirst major figure was François-René de Chateaubriand, a minor aristocrat who had remained a royalist throughoutthe Revolution, and returned to France from exile in England and America under Napoleon, with whose regime hehad an uneasy relationship. His writings, all in prose, included some fiction, such as his influential novella of exileRené (1802), which anticipated Byron in its alienated hero, but mostly contemporary history and politics, his travels,a defence of religion and the medieval spirit (Génie du christianisme 1802), and finally in the 1830s and 1840s hisenormous autobiography Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe ("Memoirs from beyond the grave").[45]After the Bourbon Restoration, French Romanticism developed in thelively world of Parisian theatre, with productions of Shakespeare,Schiller (in France a key Romantic author), and adaptations of Scottand Byron alongside French authors, several of whom began to writein the late 1820s. Cliques of pro- and anti-Romantics developed, andproductions were often accompanied by raucous vocalizing by the twosides, including the shouted assertion by one theatregoer in 1822 that"Shakespeare, c'est l'aide-de-camp de Wellington" ("Shakespeare isWellington's aide-de-camp").[46] Alexandre Dumas began as adramatist, with a series of successes beginning with Henri III et sacour (1829) before turning to novels that were mostly historicalThe "battle of Hernani" was fought nightly at theadventures somewhat in the manner of Scott, most famously The Threetheatre in 1830Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, both of 1844. Victor Hugopublished as a poet in the 1820s before achieving success on the stagewith Hernani, a historical drama in a quasi-Shakespearian style which had famously riotous performances,themselves as much a spectacle as the play, on its first run in 1830.[47] Like Dumas, he is best known for his novels,and was already writing The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831), one of the best known works of his long career. Thepreface to his unperformed play "Cromwell" gives an important manifesto of French Romanticism, stating that"there are no rules, or models". The career of Prosper Mérimée followed a similar pattern; he is now best known asthe originator of the story of Carmen, with his novella of 1845. Alfred de Vigny remains best known as a dramatist,with his play on the life of the English poet Chatterton (1835) perhaps his best work.French Romantic poets of the 1830s to 1850s include Alfred de Musset, Gérard de Nerval, Alphonse de Lamartineand the flamboyant Théophile Gautier, whose prolific output in various forms continued until his death in 1872.9

Romanticism10George Sand took over from Germaine de Staël as the leading female writer, and was a central figure of the Parisianliterary scene, famous both for her novels and criticism and her affairs with Chopin and several others.[48]Stendhal is today probably the most highly regarded French novelist of the period, but he stands in a complexrelation with Romanticism, and is notable for his penetrating psychological insight into his characters and hisrealism, qualities rarely prominent in Romantic fiction. As a survivor of the French retreat from Moscow in 1812,fantasies of heroism and adventure had little appeal for him, and like Goya he is often seen as a forerunner ofRealism. His most important works are Le Rouge et le Noir (The Red and the Black, 1830) and La Chartreuse deParme (The Charterhouse of Parma, 1839).RussiaEarly Russian Romanticism is associated with the writersKonstantin Batyushkov (A Vision on the Shores of the Lethe,1809), Vasily Zhukovsky (The Bard, 1811; Svetlana, 1813) andNikolay Karamzin (Poor Liza, 1792; Julia, 1796; Martha theMayoress, 1802; The Sensitive and the Cold, 1803). Howeverthe principal exponent of Romanticism in Russia is AlexanderPushkin (The Prisoner of the Caucasus, 1820–1821; The RobberBrothers, 1822; Ruslan and Ludmila, 1820; Eugene Onegin,1825–1832). Pushkin's work influenced many writers in the19th century and led to his eventual recognition as Russia'sgreatest poet.[49] Other Russian poets include MikhailLermontov (A Hero of Our Time, 1839), Fyodor Tyutchev(Silentium!, 1830), Yevgeny Baratynsky's (Eda, 1826), AntonDelvig, and Wilhelm Küchelbecker.Frontispiece of the 1st edition of Pushkin's epic fairy taleRuslan and Ludmila, 1820Influenced heavily by Lord Byron, Lermontov sought to explorethe Romantic emphasis on metaphysical discontent with societyand self, while Tyutchev's poems often described scenes ofnature or passions of love. Tyutchev commonly operated withsuch categories as night and day, north and south, dream andreality, cosmos and chaos, and the still world of winter andspring teeming with life. Baratynsky's style was fairly classicalin nature, dwelling on the models of the previous century.Catholic EuropeIn predominantly Roman Catholic countries Romanticism was less pronounced than in Germany and Britain, anddeveloped later, after the rise of Napoleon;

Romanticism (also the Romantic era or the Romantic period) was an artistic, literary, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe toward the end of the 18th century and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate period from 1800 to 1850. Partly a reaction to the Industrial